Half of Black D.C. residents lack easy access to health care, analysis shows

January 3, 2024 at 6:00 a.m. EST

"Nearly half of Black D.C. residents live in medically underserved areas — neighborhoods with a shortage of primary care services where the rates of heart disease, hypertension and other serious chronic conditions are more prevalent than in the rest of the city, a Washington Post analysis of federal data shows.

The numbers underscore the troubled state of health outcomes for Black residents in the nation’s capital, who for decades have been disproportionately affected by ailments like heart disease, diabetes, asthma and HIV, despite a flurry of initiatives to stem the tide. That concern is especially acute in the low-income communities concentrated east of the Anacostia River, where outcomes are notably worse than for White, Asian and Latino residents citywide.

The Post’s findings come as the District tries to rebound from the coronaviruspandemic, which had a devastating impact on Black residents, who made up more than three-quarters of D.C.’s at least 2,230 deaths but represent only half of the city’s population. The virus only exacerbated long-standing disparities, illustrating howroadblocks to health care can increase death rates and other negative healthoutcomes.

Racial disparities in health care persist due to lack of medical care in Southeast D.C.

Colonial

Village

This area has a high share of residents 65 and older, one of the factors used to designate areas as medically underserved.

49 percent of Black D.C. residents live in medically underserved areas.

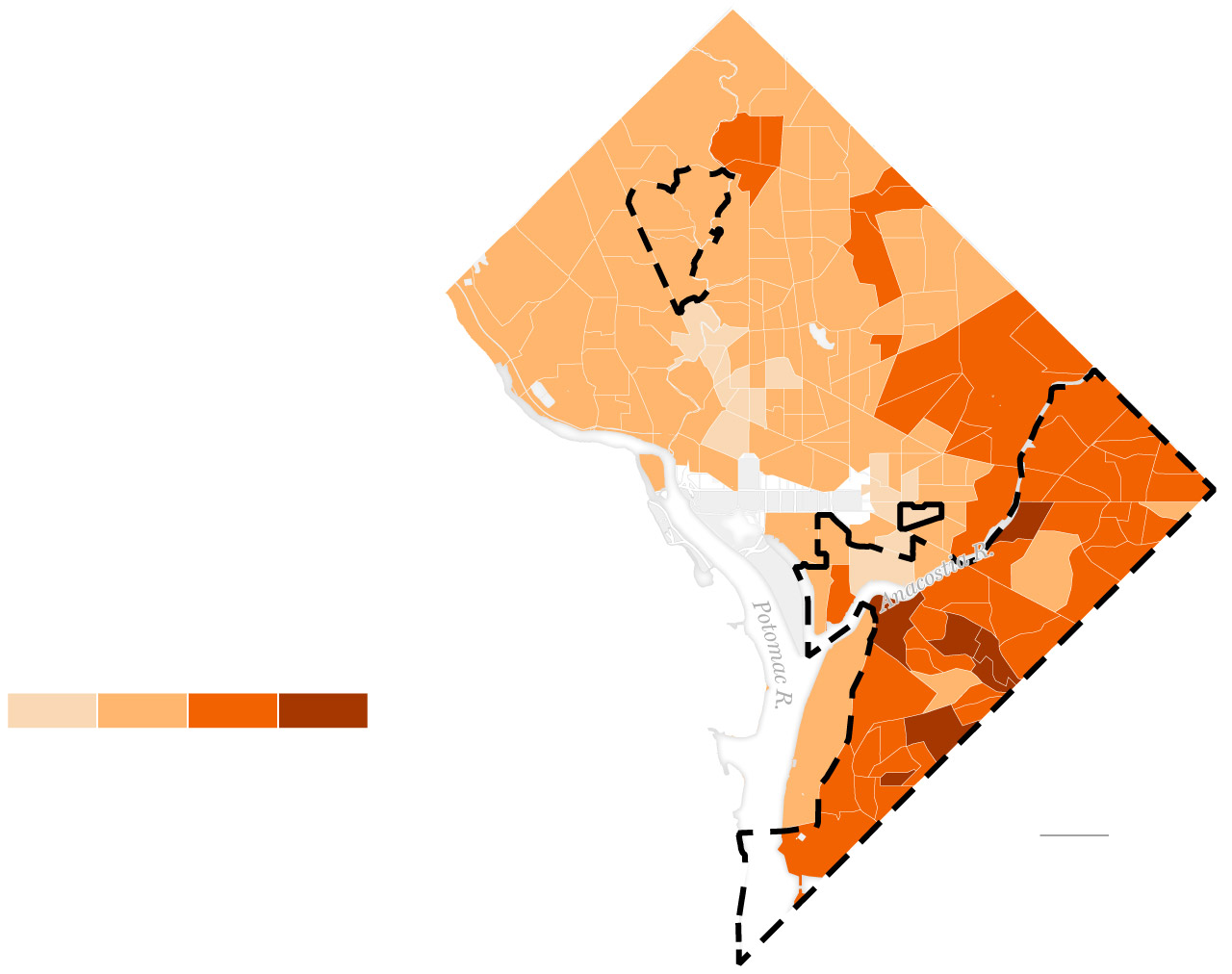

Rate of adult diabetes by census tract in 2021

Medically

underserved

area

Historic

Anacostia

The average rate of diabetes in medically underserved areas is

six percentage points higher than other areas of the District.

Congress

Heights

In addition to diabetes, residents of medically underserved areas experience higher likelihoods of obesity, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Open Data DC

While many other racial groups saw increases across causes of death during the pandemic, none approached the level experienced by Black residents. A record rate of Black Washingtonians died in each year from 2020 to 2022, hitting a mark not seen since the 1960s.

And while a new hospital under construction in one of the poorest parts of the city could be a catalyst for sweeping change, District officials say targeted interventions are needed to restore trust among the city’s most marginalized residents and meet their needs.

Sizable disparities in health outcomes between White and Black people is not a problem unique to the District. And across the country, Black U.S. residents on average have shorter lives than their White counterparts, a disparity that was amplified by the pandemic.

But the issue is especially acute in D.C., even when compared with the city’s immediate neighbors.

Data analyzed by The Post shows that a large percentage of Black residents in D.C. face more challenges with health-care access than those in Maryland and Virginia. Across the region, about 21 percent of Black residents live in medically underserved areas compared to D.C.’s 49 percent.

With 27 percent of D.C.’s overall population living in a medically underserved area, data shows the District places 18th among 35 U.S. cities with more than 500,000 residents.

D.C. government officials over the years have taken a wide breadth of actions to improve health-care access for the neediest residents, perhaps most notably by expanding health-care options to residents who lacked insurance coverage. They have also commissioned numerous studies to prescribe solutions, established an office of health equity and looked to target the endemic conditions that have hit Black communities the hardest, like AIDS. But disparities in health outcomes between Black residents and other races have only widened.

“It’s intolerable — it’s actually unacceptable — to be in the nation’s capital and have so many of our residents suffering,” said Tonia Wellons, president and CEO of the Greater Washington Community Foundation, a D.C.-area funding organization that was selected to facilitate the city’s $95 million Health Equity Fund. “Giving up is not an option. I believe there is the political will, the social will, and there is the capacity to shift the tide on some of these issues we’re experiencing now.”

The differences in health outcomes are starkest in neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River. In 2017, residents in Ward 8 — which contains the city’s highest concentration of Black residents — lived 16 fewer years on average than residents of Ward 3, the Whitest and most affluent ward in the District, according to city data. Their plight has been further complicated by increased rates of gun violence compared with the rest of the city and fewer options for nutritious, affordable food. Until 2022, there was no urgent care center in Wards 7 or 8.

Black population

in D.C. wards

Percentage by census tract

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Open Data DC

Some residents, like 63-year-old Christy Webster, say the shaky reputations of medical facilities in the immediate area have caused them to delay care or seek help elsewhere, even if it’s inconvenient.

Dealing with a cascade of health problems in recent years, Webster has frequently tried to treat them on her own because of what she describes as a lack of trustworthy and reliable health-care options around her economically underserved neighborhood in Ward 8’s Congress Heights.

When pain in her colon became unbearable last year, she drove 10 miles west to a more affluent sector of the city to see a specialist, citing insufficient options near her that accepted her Medicaid insurance.

“I have to get a colonoscopy soon, and I have to go across town, as opposed to going somewhere around here,” Webster said. “If I could just go up the street to go to a medical center, I could get home by myself.”

The United Medical Center, the only full-service hospital in Southeast Washington, will soon close permanently following years of complaints related to financial mismanagement and patient care. In 2017, after regulators detected a series of dangerous mistakes, the United Medical Center shut down its obstetrics ward.

Wayne Turnage, D.C.’s deputy mayor for health and human services and director of the Department of Health Care Finance, expressed frustration that poor health outcomes have worsened in the city’s low-income communities, even though, he noted, the District probably has more inpatient beds, primary care doctors and specialty care doctors than any comparable jurisdiction in the country.

A 2018 primary care needs assessment by the D.C. Health Department found there were plenty of doctors around — an “abundant overall supply,” in fact — but they were not evenly distributed. In Ward 2, there was one full-time physician for every 262 patients. In Ward 7, the ratio was one physician for every 4,358 residents. Similar shortages of primary care providers were observed in parts of Ward 8.

Medical services are concentrated west of the Anacostia River, Turnage said, and at United Medical Center, which serves Wards 7 and 8, most patients enter the hospital through the emergency room rather than through physician referrals.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt that the lack of a comprehensive health-care system in Ward 8 has had an adverse impact on health outcomes,” he added.

Colonial

Village

Columbia

Heights

Medically

underserved

area

Adults with poor physical health for

14 or more days in 2021

Congress

Heights

Percentage by census tract

Sources: CDC, U.S. Census Bureau, Open Data DC

Nine of 10 residents in Ward 8 rely on Medicaid, an income-based insurance program that is a stand-in for poverty. Yet while the District has more than 300,000 members in its Medicaid program, a little more than half the city, the 2018 study noted that 76 percent of D.C.’s Medicaid patients typically traveled outside their ward to receive primary care. Researchers found at the time that 40 percent of Medicaid enrollees did not receive any primary care in a given 12-month period.

Turnage and city health leaders have also pointed to the propensity of low-income people to seek emergency room care over navigating the primary care system, which requires making appointments and taking time off work — all of which could end with referrals to more doctors or a hospital stay. Last year, D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser (D) noted that the city’s 911 call volume increases annually, including calls for non-emergency medical services. To keep phone lines free for urgent health emergencies, the District more than five years ago enabled 911 operators to divert callers seeking medical help to a registered nurse through a dedicated triage line.

The nurses can help callers make telehealth appointments with a doctor, set up an appointment to visit a clinic and even arrange for transportation.

“There is a gap in making sure that people feel confident about finding a medical home,” Bowser said at the time when asked about the disparate health outcomes for Black residents. “I definitely hear it east of the river, that people want to have a hospital that they’re comfortable in. And for too long they haven’t had one.”

Public health officials and advocates say D.C.’s inequities are more heavily influenced by an array of social and economic factors like housing, education, transportation and income, drivers that affect the opportunity to have good health and also vary widely by a resident’s neighborhood.

A 2018 health equity report from the city found that social health determinants drive 80 percent of the city’s health outcomes compared with 20 percent related to clinical care — and in a place like D.C. where poverty is largely concentrated in the easternmost neighborhoods, negative health outcomes have followed a similar pattern.

The report adds: “Your zip-code may be more important than your genetic code for health.”

The battle against HIV is one example of the city’s efforts at addressing Black health disparities, with an uneven outcome. D.C. emerged as a national leader in efforts to prevent the spread of AIDS not long after the first U.S. cases were reported in the early 1980s. The city was among the earliest to appoint an AIDS director and create a dedicated office for care.

But by the mid-’90s, city officials were being scrutinized for their prevention efforts as the number of deaths from the virus rose drastically and increasingly among Black residents; in D.C., unlike many other cities, Black residents had always made up at least half of those infected with AIDS, The Post reported in 1993. Former mayor Tony Williams, who served from 1999 to 2007, fired the director of his HIV/AIDS administration in 2005 soon after the D.C. Appleseed Center for Justice and Law issued a report criticizing city leaders for their handling of the epidemic. The Appleseed report also accused the District or being 10 to 15 years behind schedule in creating an effective effort to mitigate the spread of HIV.

“We weren’t getting any kudos for [our HIV management], and for justifiable reasons,” Williams said in an interview.

Around 2009, D.C.’s rate of HIV infection was still the highest in the nation — greater than some countries in West Africa. A Post exposé found the city’s efforts to throw millions of dollars at the problem were largely mismanaged; $25 million awarded by D.C.’s HIV/AIDS Administration from 2004 to 2008 went to nonprofits that delivered questionable or substandard services. And even though Wards 7 and 8 were the hardest hit by the virus — one-fourth of residents with the disease in 2009 lived east of the Anacostia River — just 6 percent of $100 million earmarked for prevention and treatment services went to groups that specialized in these neighborhoods.

Families east of the Anacostia River seeking HIV services were forced to scramble for care in other parts of the city as a result, The Post found.

Today, D.C. has reduced the number of new cases of the disease. Officials have credited the overall reduction in new HIV diagnoses to the success of the city’s needle exchange program — which had been blocked by Congress for a decade — and increased uptake of PreP, a pre-exposure pill that greatly reduces the risk of HIV infection.

But that’s still the most HIV cases per capita and nearly three times the national rate, according to a KFF analysis of CDC data. And Black residents are still disproportionally infected with the virus: The city also found in February that 71 percent of the 11,904 people that were living with HIV in the city in 2021 were Black — and the vast majority of those cases are still concentrated east of the Anacostia River.

Ayanna Bennett, director of the D.C. Health Department, said the sheer size of the District’s Black population commands attention from city leaders, unlike in San Francisco where she previously was the health equity officer. There, she said, negative outcomes for the relatively small Black and Pacific Islander communities could get lost in data that portrayed a healthy city on average.

Cedar Hill Regional Medical Center, the new hospital affiliated with George Washington University Hospital under construction east of the Anacostia River, promises to begin to reverse long-standing disparities. Bennett said resources must be put into addressing child care, flexible scheduling and health-care literacy for residents — such as when to seek care and why — for the hospital to make a lasting impact on the health of the community.

“What we often do is we give a resource … [without] putting sufficient resources into fixing the barriers that would prevent people from using it. Then we regret having done it because, ‘Oh my God, we put all that money in and they didn’t use it,’” Bennett said.

Before the pandemic changed everything, she said, health outcomes and life expectancy for Black residents were beginning to improve thanks to Medicaid expansion and a concerted focus on equity.

“We took four steps forward,” Bennett said. “And now we’ve taken two, three, five, six steps back depending on the community you’re talking about, but to me that means we can move forward.”

Sitting in her home on a recent sunny afternoon, Webster wondered if the new hospital will live up to its promise. A former educator for children with special needs, she recalled that some of her peers in the field were hesitant to work in Southeast Washington, where residents’ incomes were generally lower.

“I’m curious if we’ll still get the same type of care as other facilities, or is it going to be minimal? Is it going to be somewhere that can be trusted? Will we get the best?” Webster asked. “A lot of therapists that did the same work that I did didn’t want to come to my side of town. I wonder if that would be the same with doctors — will they choose to come over here?”

In 2021, Bowser convened the city’s first Health Equity Summit aiming to explore the connection between health disparities exposed by the coronavirus with structural racism and social health determinants like housing, transportation and income, which were described by summit organizers as “the root cause of most health inequities.” While the city’s median household income is about $104,000, the average income for Black households is $75,000 (it is $160,000 for White households).

That same year, as part of a legal settlement with the District, Bowser announced that the insurance company CareFirst had agreed to establish D.C.’s first Health Equity Fund, with a mandate to distribute $95 million to community-based nonprofits over five years to explore ways to mitigate these systemic issues.

The Greater Washington Community Foundation, which oversees the fund, has also made health determinants an emphasis in its process. The foundation in its first two rounds of funding has awarded grants to dozens of nonprofits with initiatives in the realms of improving economic mobility and direct services, as well as organizations focused on shifting legislative policy in the D.C. Council.

The health equity grants add to the long list of city initiatives to reduce disparities. In 2022, Bowser announced a $92 million investment in several capital projects focused on creating more balanced health-care access, including the expansion of Whitman-Walker, a community health center with expertise in HIV/AIDS health care, into Ward 8. During a Dec. 11 news conference to celebrate an additional $22.5 million from the U.S. Treasury to support Whitman-Walker’s expansion, Bowser and health leaders highlighted how it would help Whitman-Walker support thousands of new patients — but also help address social health determinants.

The development will help create more than 100 new jobs in the ward with the city’s highest unemployment rate, and contain community spaces for workshops related to interviewing and building résumés, said Bowser, who acknowledged feedback from the Ward 8 community about barriers to accessing health care.

“Fundamentally, what Whitman-Walker is trying to do is be part of the solution, with District partners, to eradicate health disparities in Ward 7 and Ward 8,” said Naseema Shafi, CEO of Whitman-Walker Health. “This is a once-in-a-generation chance to advance health equity.”

But even as those efforts come to fruition, experts note the city will need to re-earn the trust of longtime residents who feel forgotten, like Webster, who has battled depression ever since physical ailments took over her life a few years ago. Her colonoscopy is now set for February, and the grandmother said she is eager to start feeling healthy again.

Black mortality rates could continue to grow disproportionately. Bowser recently declared a public health emergency on another issue disproportionately killing Black Washingtonians: opioid overdoses. Advocates stress the need for stable housing before treatment and recovery can be part of the discussion.

“We can’t hide the fact that as the city has progressed, certain populations and people have been marginalized, displaced and not included in that progress. And while we’ve made some strides over the years, important investments, it’s not been enough and it’s not been consistent or sustained,” said Wellons, the community foundation’s president. “That’s why we’ve seen things worsening.”

For this analysis, The Washington Post used a combination of data from the U.S. Census Bureau and a database of communities deemed medically underserved that is maintained by the Health Resources & Services Administration.

The Post highlighted the prevalence of health risk factors — like heart disease and physical health — for each ward in D.C. using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 500 Cities Project.

That data, which contains tract-level geographies, was merged with both non-medically and medically underserved tracts to compare the rates of risks against both. Lastly, the rate of mortality was calculated using CDC’s Wonder database, using age-adjusted data to account for the varying ages of D.C. residents.

Story editing by Jennifer Barrios. Photo editing by Mark Miller. Copy editing by Colleen Neely and Shay Quillen. Design by Jennifer C. Reed. Data editing by Anu Narayanswamy.

No comments:

Post a Comment