More people are dying in Puerto Rico as its health-care system crumbles

“Islanders died of chronic conditions and covid-19 in 2022 at numbers that surpassed even Hurricane Maria’s toll

Photography by Erika P. Rodríguez

Nov. 28 at 6:00 a.m.

AGUAS BUENAS, Puerto Rico — In a purple house along a narrow road in Puerto Rico’s Central Mountain Range, Margarita Gómez Falcón’s breathing suddenly grew labored one March evening. She called an ambulance and began a grim two-hour wait for paramedics to arrive.

Health services across this self-governing island have been deteriorating for years, contributing to a surge in deaths that reached historic proportions in 2022, an investigation by The Washington Post and Puerto Rico’s Center for Investigative Journalism has found.

The case of Gómez Falcón, 67, underscores the many ways a faltering medical system has contributed to elevated death rates. She had struggled with kidney disease, covid-19, and breathing problems requiring the use of oxygen. But access to dialysis and other specialized medical care had dwindled, especially since Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017.

Aguas Buenas, a small, working-class town in the central highlands, had one working ambulance for its 25,000 people when Gómez Falcón called for help, so dispatchers sent a private one that had trouble finding her home in the town’s winding back roads. As her breathing slowed, her family members said, they gathered around her and prayed for paramedics to arrive in time. When they finally pulled up, she was already dead.

“At one point, she just leaned back, closed her eyes and she was gone,” said her sister, Carmen Gómez, 62.

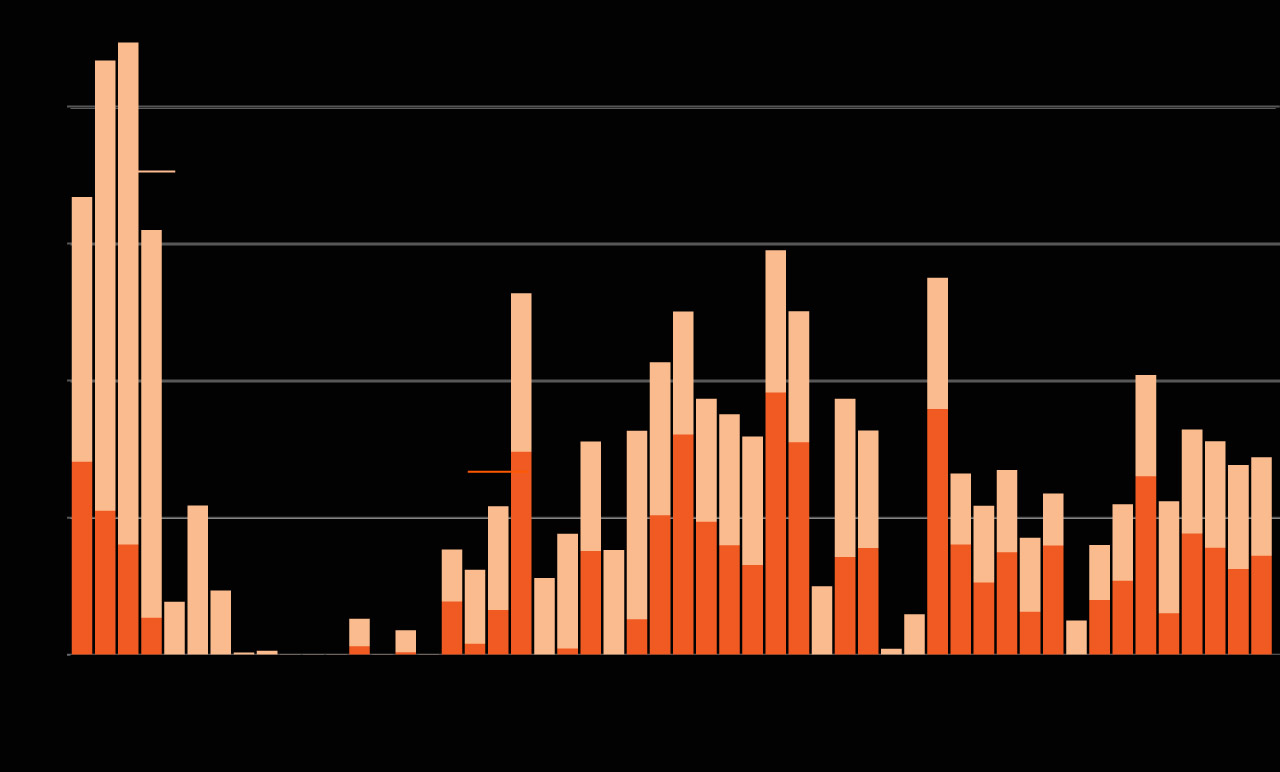

Puerto Rico, with a population of 3.3 million people, experienced more than 35,400 deaths last year. That’s nearly 3,300 more than researchers would ordinarily expect based on historic patterns, according to a statistical analysis by The Post and Puerto Rico’s Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI).

This “excess mortality” — a term scientists use to describe unusually high death counts from natural disasters, disease outbreaks or other factors — resulted in part from a covid spike early last year that killed more than 2,300 people, health data shows.

But elevated death rates continued in the months after covid subsided, indicating a broader breakdown as the island lost medical staff and services and younger Puerto Ricans moved away, leaving behind a population that is increasingly elderly and facing age-related health complications.

The recent jump in mortality is the latest warning sign that years of natural disasters and financial crises have taken a deadly toll. Last year’s spike was concentrated among Puerto Ricans over age 65, with other age groups dying at more typical rates, the analysis found. If Puerto Rico had a more typical population of younger people, the death rate in 2022 would have been the same or potentially even lower than in the rest of the United States, the statistical analysis showed.

“These types of events, both hurricanes and earthquakes, as well as pandemics, have made evident the vulnerability of many older adults who live alone, many of whom live below the poverty line, who do not have the most basic resources to face that type of adversity,” said José Carrión-Baralt, a professor in the gerontology program at the Recinto de Ciencias Médicas Graduate School of Public Health in San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital and biggest city.

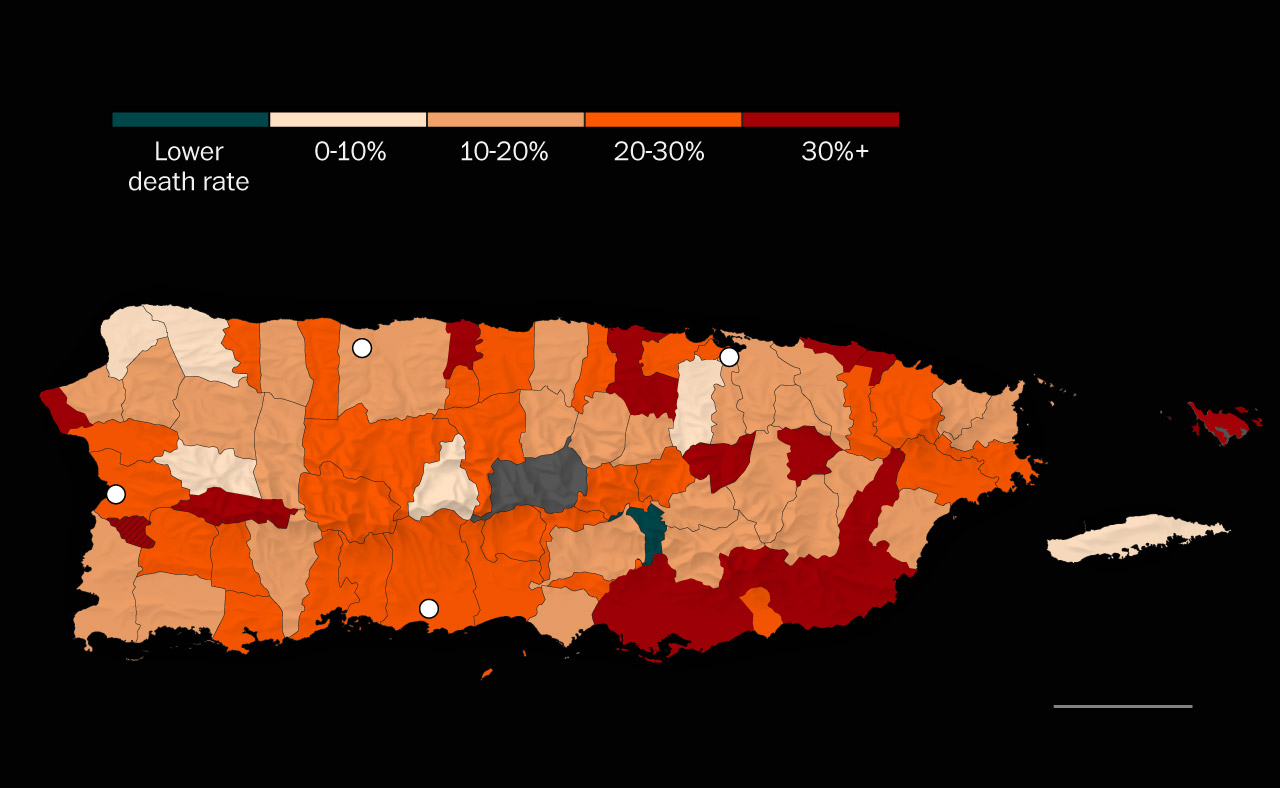

Last year, 110 Puerto Ricans died per 10,000 residents, a rate that is nearly 11 percent higher than in the United States overall. That marks a reversal from years past, when the island had lower or similar death rates compared with the United States as a whole. Even the wealthiest Puerto Ricans experienced death rates last year similar to those long suffered by poorer communities.

Puerto Rico’s death rate in 2022 surpassed that of any other year in the past two decades, including 2017, when Hurricane Maria devastated large swaths of the island, according to the analysis. The increase in deaths appears to have continued into 2023, with preliminary data for the first quarter showing that the death rate remained elevated.

“It’s been nearly six years since Maria, and nothing has been resolved,” said Nereida Meléndez‚ a community activist in Aguas Buenas. “Here there are bridges that no one has done anything for. There are damaged highways no one has done anything to fix. Here one says, ‘What about that money they sent us? Where is it? What are they doing with it?’”

Puerto Rico’s Health Department has acknowledged that the island’s mortality rate rose to unusual heights in 2022, although its statistics are slightly different from the ones found in this analysis because researchers used different estimates for each municipality’s population. Officials have said they believe covid played a role in the surge of deaths, as did the shortage of doctors on the island, but health officials did not investigate the causes in their analysis.

“Right now, the conversation has focused on the cause of greatest impact, covid-19, which triggered the highest number of hospitalizations and deaths,” said Melissa Marzán Rodríguez, chief epidemiologist for Puerto Rico’s Health Department.

The analysis by The Post and the Center for Investigative Journalism, which is the first to comprehensively examine the reasons for the surge in mortality, confirms the role of covid and the shortage of doctors, but also points to other problems.

Puerto Rico’s leading killers last year were covid, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, drug overdoses, kidney disease and dementia — most of which are potentially less lethal with routine medical care.

Health data shows that in 2022, compared with the historical average from 2015 to 2021, deaths from Alzheimer’s increased by 26 percent, heart disease by 11 percent and mental health causes by 53 percent, with most of those deaths from substance abuse or dementia. Alcoholism also was listed as a leading cause of death.

Reversing Puerto Rico’s surge in death rates, experts said, would require addressing social, economic and political problems that have undermined medical services for those who need them most.

The death rate in Aguas Buenas increased by nearly 50 percent in 2022 compared with the town’s historical average — the largest increase of any community in Puerto Rico.

Gómez Falcón’s death certificate said that she died of a heart attack and that she also suffered from respiratory and kidney failure. But her family is haunted by the thought that she might have survived.

The state agency that dispatched the private ambulance said the problem was poor communication, not a systemic decline of medical systems. “The delay was not due to a lack of resources,” said Javier Rodríguez, commissioner of the state Emergency Medical Corps, in a statement. “Paramedics tried but failed to reach the caller for directions or a point of reference to get to the right location.”

The family of Gómez Falcón, however, sees a cascading series of failures, with the delayed ambulance just one problem among many undermining the health of Puerto Ricans — especially older ones.

“I know my sister wasn’t the only person who experienced this,” Carmen Gómez said.

As Puerto Ricans strove to rebuild in the months after Maria struck, an estimated 120,000 people — most of them of working age — moved away, according to the U.S. census. Accelerated migration continued through the end of the decade, and birthrates also fell. Puerto Rico’s overall population fell by nearly 12 percent from 2010 to 2020.

Sicker and older adults were left behind, making Puerto Rico one of the most rapidly aging societies on the planet. More than 1 in 5 residents are now over 65, which is higher than the U.S. average, according to an analysis by Hunter College’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies.

The population of Aguas Buenas, a city founded in the 19th century and named in honor of the crystal-clear water that flowed through its springs, shrank by nearly 4,500 residents after Maria, a drop of nearly 16 percent from a decade earlier.

But the population of those over 65 grew by about 9 percent, a shift that by itself can increase death rates because elderly people are more likely to die in any given year than younger ones.

On the streets of Aguas Buenas, the graying of its residents is as vivid as the ruby blossoms of its flamboyán trees. Elders stroll through the plaza clutching word-puzzle books while matriarchs sit perched on balconies watching comings and goings. The waiting rooms of local clinics run three rows deep with seniors. And the neighborhood bakeries are havens for old friends comparing notes on blood pressure medications.

It’s not just Puerto Rico’s young who have left. Doctors, including some who saw their clinics damaged by hurricanes and earthquakes, increasingly are in short supply, with about half of the town’s 15 physicians having moved away, people here said.

“Aguas Buenas has been a ghost town,” said Mayor Karina Nieves Serrano, who won a special election for a vacated seat last year. “We are trying to find ways to reawaken its self-image.”

In Puerto Rico overall, government data shows there are more than 400 fewer doctors than in 2019. Less than a third of the island’s municipalities have hospitals with accessible beds, with some Puerto Ricans living up to 20 miles away from the nearest facility, according to data from Puerto Rico’s Heath Department. In 2022, municipalities with no hospitals saw greater death rates than their historical averages.

Aguas Buenas itself has only ever had one small emergency room, leaving residents to rely on a few small clinics. Mariemma Jiménez works for one of the newer ones, NeoMed, helping to identify and eliminate barriers to care. She roams the remote barrios, setting up preventive-health fairs, arranging transportation for patients and educating poor farmworkers.

She estimated that most of the clinic’s patients are over age 60 and managing serious chronic disease. Bus service also has been cut, making it harder for those without cars to seek care amid a general deterioration of public services and political turmoil.

“It’s a demoralized population with many transportation needs living in far-flung barrios. These are people who are used to going to the doctor only when they are sick or in pain,” Jiménez said. “That’s where I see the breakdown.”

Puerto Rico’s public health system was once the envy of the Caribbean. Then-Gov. Pedro Rosselló privatized it in the 1990s, in what became known as “La Reforma.” Most government-owned hospitals were sold in an effort to control costs and streamline operations. But the opposite took place: By 2006, Puerto Rico’s economy tanked and public debt ballooned — in part, because of government borrowing to cover skyrocketing health costs.

The massive flight of doctors began then. In 2010, there were approximately 19,000 physicians on the island. As of 2022, there were 10,846, of whom 3,000 have active medical licenses but also practice in the mainland United States, according to data from the Colegio de Médicos Cirujanos of Puerto Rico.

Heart disease is a leading cause of death in Puerto Rico, with rates increasing 11 percent in 2022. But there are only 95 cardiologists — or one for every 17,500 adults between ages 18 and 64 — to treat them. It’s the lowest ratio among all U.S. jurisdictions, according to the American College of Cardiology. The national average is one per every 7,000 adults.

Many of Puerto Rico’s cardiologists are themselves older than 65 but continue practicing because there are no younger physicians to take over their growing patient loads. Medical professionals leave the island largely because of low pay and poor working conditions, physicians and experts said.

It can take six to eight months, residents and physicians said, for patients to be seen. Urgent cases are managed as they come but interventions are sometimes too late, after more serious problems develop.

“All of that pressure weighs on you,” said cardiologist Luis Rosado Carrillo, who has 17,000 patients on his roster. He sees about half of them on a regular basis. “We are overwhelmed.”

During the pandemic, the terror of contracting covid kept geriatric patients away from the practice of family physician Belinda Rodríguez, who is based in Bayamón, a suburb of San Juan. Many opted for telehealth as their primary means of care, but when they returned for in-person visits as the pandemic waned, there was a “total decline” in their overall health, she said.

Their underlying conditions had worsened and many had developed insomnia, depression and anxiety, she said.

“It accumulates,” said cardiologist Luis Molinary Fernández. “And then you have a catastrophe.”

Patient advocates said the hardships of staying healthy in Puerto Rico push many to resign themselves to declining health.

“We all have to die of something,” said Wilfredo Ramos, 61, a stroke survivor who lives deep in the remote peaks of the Central Mountain Range, one of the most challenging topographies on the island.

In 2020, Ramos fell unconscious, and three days passed before someone found him bleeding near his bed after a massive brain hemorrhage inside his rural home, where he lived alone. He lost the use of one side of his body, can’t drive and has frequent fainting spells.

Karina Quiñones, who works with a community clinic, asked Ramos during a recent visit, “When was the last time you saw a doctor?” as she rummaged through a tub of seven prescription bottles.

“Maybe more than 18 months,” he replied. “Who’s going to take me?”

Quiñones, also a nurse, swallowed hard: “These scripts tell me you have high cholesterol.”

“And a heart condition,” Ramos added.

He said he was lonely and ashamed of his inability to fix anything in his life. His old house leaked after earthquakes left cracks in the kitchen. He had trouble being understood well enough on the phone with his insurer to schedule appointments. So he stopped trying to remedy his own health, apart from taking pills and some exercises to regain leg movement. Instead, he tinkered with what he could manage, repairing broken speakers and radios with his collection of old electronic parts.

“Sometimes I just sit in bed waiting for the hours to go by,” he confessed.

Some Puerto Ricans fashion workarounds and call in favors to coordinate health care, score lifesaving pills or get elusive cardiologist referrals. Families pay out of pocket for private ambulances or taxis because there are few public means to transport incapacitated loved ones to medical facilities. Some put fragile relatives into the back seat of whatever car is available for journeys to other cities for care.

“If we don’t do it, it doesn’t happen. It’s one problem after another that complicates health,” said Roberto Colón, 56, who lives in a city near Aguas Buenas and recently paid a private ambulance driver to bring his elderly mother home from surgery. “The Puerto Rican who loves this place will stay, but it will come with sacrifice.”

At the Cementerio Municipal 1 in Aguas Buenas, workers installed a new aboveground tomb on a recent afternoon.

The graveyard, like most in Puerto Rico, is at capacity, in part because of poor planning and limited resources, but also because too many people are dying. A patch of dirt the length of about two parking spaces is all that’s left for the municipality to construct additional plots.

Across the street from the cemetery is the Monte Santo funeral home, one of two in Aguas Buenas. The local Facebook page, “What’s happening in Aguas Buenas,” is maintained by the other funeral home director, Carlitos Román, who posts a seemingly endless stream of funeral notices.

“We normally do about 140 to 150 services a year,” said Monte Santo director Héctor Montañez, looking at his 2022 records. “We are at 201. That’s the highest number in the 40-year history of this business.”

Meléndez, the community activist, said she grows depressed thinking about how her mostly elderly neighbors and relatives fight to stay healthy amid mounting pressures.

“Everything here is just hard,” Meléndez, 66, said while wiping sweat from her forehead. “Don’t tell me that I need to go to the United States because here I don’t have what I need. We deserve better services and a higher quality of life here.”

Gómez Falcón once presided over a large extended family living on a sloping mountainside with panoramic views. As health services deteriorated, she battled an inherited kidney disease that required regular dialysis, with the catheter often getting misplaced or stuck. Bacteria sometimes found its way inside the artificial blood vessel under her skin. It was a lot to manage, family members said, but Gómez Falcón did it alone so as not to burden anyone else.

The strain grew far more severe when Hurricane Maria swept her wooden home off the face of the mountain in 2017. The Category 4 storm with winds of up to 175 mph flattened 1 in every 10 homes in Aguas Buenas, according to local estimates.

Gómez Falcón was hospitalized in the nearby town of Cayey, where she underwent dialysis — with generators powering her treatment — three times a week. She came home to nothing but debris.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency helped Gómez Falcón rebuild the family home. But she caught covid and was hospitalized with breathing difficulties during a trip to Ohio the following year to visit three of her children for Christmas. She was never the same after that, reliant on oxygen 24 hours a day, family members said.

By February 2022, she suffered a new setback when her oxygen levels dipped dangerously low. Gómez Falcón survived because she reached the hospital in time.

She was not as lucky the next time she called for the ambulance, just three weeks later.

Gómez Falcón was cremated. Her family said she was ready to be reunited with her late husband of nearly 50 years.

Her daughter Catherine Meléndez spent her grieving months rearranging her mother’s house and discarded the chair where she took her last breath. One day her grandmother — Gómez Falcón’s 88-year-old mother — handed Meléndez her mother’s wedding ring.

Meléndez slid it through a silver necklace, where it sits close to her heart.

correction

A previous version of this article incorrectly said that 110 Puerto Ricans died per 1,000 residents last year. The data shows that 110 Puerto Ricans died per 10,000 residents last year. The article has been corrected.

About this story

This report is the result of a joint investigation by The Washington Post and the Center for Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit news organization in Puerto Rico.

Methodology

The Post used National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) weekly counts of death by jurisdiction and age when calculating and comparing rates of death in Puerto Rico with the United States overall. For all other analyses, the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (Center for Investigative Journalism) and The Post acquired, cleaned and standardized mortality records data from the Puerto Rico Health Department’s Demographic Registry in conjunction with Census Population Estimates since 2015. The Post used historical data on all deaths from five years before the covid-19 pandemic to estimate expected weekly deaths for different age groups for all of Puerto Rico using a robust regression model. Using a robust regression ensures that outliers like deaths following natural disasters do not heavily influence estimates. When analyzing specific causes of death and municipalities, The Post compared 2022 figures with historical averages and rates between 2015 and 2021. For the investigation, data was analyzed based on standard groupings in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 113 major causes of death. Historical counts of doctors and current hospital counts per municipality were provided by Puerto Rico’s Health Department.

Credits

Video editing by Angela Hill. Photo editing by Natalia Jiménez. Design and development by Rekha Tenjarla. Design editing by Betty Chavarria. Copy editing by Vanessa Larson. Editing by Christine Armario, Renae Merle and Craig Timberg. Data editing by Anu Narayanswamy.“

No comments:

Post a Comment