Anti-abortion pregnancy centers are deceiving patients – and getting away with it

“Patricia Henderson stood in the parking lot next to the Florida Women’s center in Jacksonville, wearing a white lab coat and greeting patients as they emerged from their cars. Their abortion appointments, she told them, were in the flat-roofed building across the road.

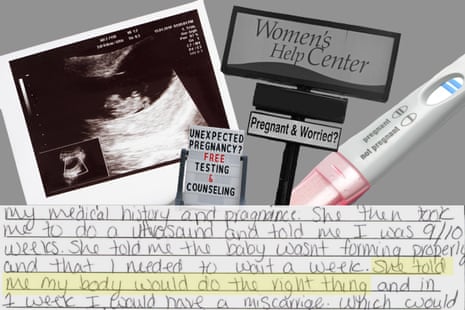

Once inside, Henderson handed them three pages of paperwork to fill out – questions about everything from their highest level of education to the date of their last period. State investigative documents lay out what clients say happened next: she led them to a pink-walled ultrasound room, where she would reveal their pregnancies in grainy images that, according to leading medical groups, only a licensed physician or a specially trained advanced practice nurse should interpret.

Henderson told one woman that abortion causes breast cancer – a claim widely disputed by medical research.

She informed another that she was not pregnant and just had a stomach virus. According to the state report, that wasn’t true.

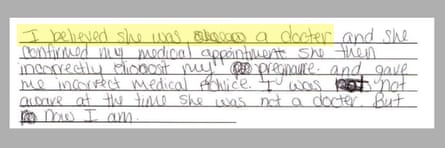

Henderson allegedly told a third woman not to bother getting an abortion because her nine-week-old embryo wasn’t “forming properly” and she would probably lose the baby anyway. “She told me my body would do the right thing and in one week I would have a miscarriage. Which would save me $555!” the woman wrote in her complaint to the state. A doctor later determined that the pregnancy was normal.

In the most serious accusation against her, Henderson told yet another woman that “the baby was stuck” in her fallopian tube, a potentially catastrophic complication known as an ectopic pregnancy. If not treated immediately, the condition can lead to major hemorrhaging and, sometimes, the mother’s death. But Henderson allegedly advised the woman to “relax at the beach” and come back in a few days. Fortunately for the woman, Henderson was wrong. The five-week-old embryo was where it should be, in the uterus.

The women later discovered they weren’t at the abortion clinic they’d intended to visit, but at the similarly named Women’s Help center, one of more than 2,500 crisis pregnancy centers across the US that aim to discourage people from getting abortions. Henderson, then in her early 70s, wasn’t a “cancer doctor”, as she allegedly informed one client, or indeed any type of licensed medical professional. Her only medical experience was as a radiation therapy technologist, and her license had expired 10 years earlier.

Nor was there a doctor on hand to review the ultrasound images Henderson took, as is considered best practice by mainstream medical organizations and the pregnancy center industry itself. The Women’s Help center – which has four locations in the Jacksonville area – did have a volunteer medical director, according to tax filings, a family practitioner then in his mid-80s. But he wasn’t involved in daily operations – “never saw clients and did not provide medical advice,” the clinic’s executive director, Nancy Basham, told Florida department of health investigators in 2018, according to a never-before-published reportobtained by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting. Basham declined to comment.

Anti-abortion pregnancy centers like the Women’s Help center have proliferated in recent decades, with many aiming to expand their capacity now that Roe v Wade has been overturned. By design, an increasing number look and operate much like traditional OB-GYN providers, offering ultrasounds, tests for sexually transmitted infections and, in some instances, even some prenatal care. Many boast of having medical directors and other licensed staff. Dozens include the word “medical” in their names.

But as the newly unearthed Jacksonville case highlights, beneath the veneer of medical professionalism is an industry that state and federal authorities have done almost nothing to regulate.

Only a few states require pregnancy centers that provide medical services to be formally licensed as clinics, a Reveal investigation has found. And, because their views are grounded in a particular ideological viewpoint, the centers aren’t subject to many other rules designed to protect patients – rules that would require them to be transparent about their operations and medical credentials.

The lack of significant regulation means that in most of the country, for the hundreds of thousands of clients whom pregnancy centers serve every year, there is no one playing an oversight role to make sure that centers are offering high-quality care and accurate information or that staff are licensed and adequately trained. No one protecting clients’ ultra-sensitive personal information or inspecting facilities and equipment to verify that they’re clean and up to date. No one taking substantive action if clients are mistreated or deceived.

Yet for decades, misleading consumers has often been a key part of pregnancy centers’ business model, numerous researchers and advocacy groups have found. One well-known tactic is to open shop near abortion clinics – sometimes even mimicking their names and logos – in an attempt to intercept their patients. Basham acknowledged this strategy in a seven-minute video targeted to Women’s Help center donors. Women who already have an abortion scheduled, she says, “come to us thinking we are the abortionist.” (The abortion clinic next door to the center closed in November when its medical director retired.)

Anti-abortion groups have fought hard against attempts to rein them in, arguing that the first amendment shields them from increased scrutiny under consumer protection laws. In 2018, the US supreme court agreed, throwing out a California law that required pregnancy centers to disclose if they weren’t a licensed medical provider and ruling that the law violated their right of free speech.

The result is what Teneille Brown, a law professor and bioethicist at the University of Utah, calls “a regulatory dead zone” that allows pregnancy centers “to dodge all of the legal safeguards that attach to actual health care without being held to even basic consumer protection standards”.

The consequences extend far beyond the reproductive health front, Brown added. “It muddles medical trust,” she said. “They trade on the goodwill of legitimate medicine to defraud patients.”

The Women’s Help center case is an egregious, and unusually well-documented, example of just how little authorities are doing to hold pregnancy centers accountable, even when the evidence – and the risks to women – are significant.

The center came to the attention of state investigators after an abortion patient filed a complaint in early 2018. The Florida department of health ultimately documented seven incidents involving Henderson from February 2016 to March 2018, issuing a cease-and-desist notice in April 2018 that prohibited her from providing health care without a medical license. The department said its action against Henderson was the most it could do in an “unlicensed activity investigation”. There was one other avenue for accountability: practicing medicine without a license is a felony in Florida. The department referred the case to the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office, but investigators there decided the behavior wasn’t “criminal in nature”.

It’s unclear whether Henderson is still involved at the center; she is not listed on its websites or in its tax filings. She didn’t return calls seeking comment.

Meanwhile, the center didn’t face any apparent repercussions for permitting Henderson to perform diagnostic medical procedures without a valid license.

Even as the state investigation was under way, Henderson was meeting with – and deceiving – abortion seekers. In one incident that isn’t in the state report, an abortion patient accused Henderson of collecting her private medical information under false pretenses, then refusing to hand over the paperwork after she realized she had been lied to.

By the time the young woman found her way to the abortion clinic next door, she had missed her appointment. She was able to reschedule, but four years later, the trauma lingers. “I was sobbing,” she recalled in a recent interview. “I was so upset.”

How pregnancy centers moved into medical services

The first pregnancy centers were founded in the late 1960s as grassroots charities that opposed abortion on religious grounds. They offered spiritual counseling and free items such as maternity clothing and diapers.

The move into medical services began more than a decade later, as centers started offering free pregnancy testing. After a client sued, a California judge ruled that organizations administering or interpreting such tests needed to be medically licensed. But centers quickly found a workaround: giving out tests for women to take and interpret on their own.

The medicalization of pregnancy centers became a core strategy of anti-abortion activists in the 1990s following the advent of the ultrasound machine. They saw its potential to change women’s minds by offering a so-called “window to the womb”. “Mothers contemplating abortion will have the opportunity to see the wonderful handiwork of the Creator move, kick and dance in celebration of life,” the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates, which provides legal and education support to the pregnancy help movement, enthused on its website.

Since then, centers have ramped up their medical services as a way to expand their reach and build credibility with clients, communities and donors. These days, 79% of centers provide free ultrasounds and 30% offer testing for sexually transmitted infections, according to the Charlotte Lozier Institute, an anti-abortion thinktank.

Even as pregnancy centers have become more medicalized, complaints about their deceptive tactics have intensified. But there’s been very little scrutiny of how these centers operate under the regulatory radar.

So Reveal set out to understand how pregnancy centers have managed to get away with practices that would get other types of healthcare providers into trouble with regulators and consumers.

We examined the publicly available materials for about two-thirds of pregnancy centers in the US – nearly 1,700 centers in 27 states. Our analysis included reviews of state laws, federal tax filings, center websites, professional licenses and how-to information for pregnancy centers seeking to add medical services.

We found that there’s shockingly little oversight of the pregnancy help industry. The vast majority of states don’t require centers that provide medical services to be licensed or inspected. In many states, tanning salons, massage parlors and even pet stores face significantly stricter oversight.

Instead, pregnancy centers typically recruit licensed doctors, nurses and sonographers as part of their teams of staff and volunteers, then piggyback on their professional licenses to legally provide medical services. It’s a system that works for other types of medical clinics because they face many additional levels of oversight. These include the federal patient privacy law known as Hipaa, regulations that govern Medicaid and Medicare, and accreditation rules for the larger hospital systems to which many traditional clinics belong.

But because the vast majority of pregnancy centers don’t charge for their services and aren’t part of hospital systems, they escape those layers of scrutiny, too.

Contrast that with the level of regulation faced by the very abortion clinic the Women’s Help center went to such lengths to mimic. For years, Florida abortion providers have been subject to annual inspections and visits from investigators at the whiff of potential problems; those inspection records are easily accessible to the public online. Under state law, there are rules about dressing rooms, ventilation, “adequate lighting” and “appropriate lavatory areas”. Abortion clinics even have to post their current state licenses “in a place that is conspicuous to all patients”.

Yet Florida investigators ended up at the Women’s Help Center only after one patient finally came forward, triggering a broader review. Even when the state department of health did substantiate those complaints, it did not make the report public. The case came to light only after Reveal filed a series of public records requests with Florida agencies.

Other notable findings from Reveal’s analysis:

Most pregnancy centers don’t list a medical director in their publicly available documents. According to the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates, pregnancy centers that provide ultrasound services should have a medical director who is a licensed physician. But in Reveal’s examination of websites and tax filings for centers that advertised ultrasound services, only a third explicitly noted having a medical director – and many of those directors maintain their own practices or work as volunteers, raising questions about how much time they spend supervising centers’ services. Some centers said they had a licensed physician on staff or working as a volunteer, though not in the medical director role.

Medical directors at many centers specialize in fields outside of reproductive health. While most of the directors identified by Reveal are OB-GYNs or family medicine doctors (whose training includes women’s health), others have careers in internal or emergency medicine. We also found six pediatricians, a urologist and a rheumatologist.

Centers often make it difficult to find out who works there and to check their credentials. The vast majority of center websites provide no information about medical staff. Many other centers disclose staffing information only on tax filings or donor-focused websites that use sophisticated search optimization tools to make themselves less visible to consumers.

The reports from the Women’s Help Center echo stories told by OB-GYNs from around the country, underscoring how reproductive health providers are often held to higher medical standards than abortion foes.

“In any other field of medicine, this would not be tolerated,” said Dr Jasmine Patel, an OB-GYN in California associated with Physicians for Reproductive Health. “How can you just set up shop and claim to be medical but have no medical training?”

Why ultrasounds should be performed by professionals

In the early prenatal period, ultrasounds are used to confirm and date the pregnancy and detect early signs of a heartbeat; later, they show whether bones and organs are growing normally and reveal the baby’s sex. Early-pregnancy ultrasounds are invasive, involving a probe inserted into the patient’s vagina and strict protocols to avoid spreading germs and STIs.

Only four states have laws requiring sonographers to be licensed. But because the technology is so complex and the stakes are so high, mainstream medical groups like the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine state that only technicians or nurses with training in obstetric sonography should perform prenatal ultrasounds, while a physician or an advanced clinical provider should interpret those results.

The pregnancy help industry echoes those standards in its written materials going back at least two decades. The three leading national groups subscribe to a “Commitment of Care and Competence” that they encourage members to post prominently in their centers. It pledges that medical services will be provided “under the supervision and direction of a licensed physician,” in accordance with “pertinent medical standards” and “all applicable laws”.

“Ultrasound is a diagnostic procedure that must be supervised and directed by a licensed physician experienced in ultrasound,” the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (Nifla) says on its website.

The groups wouldn’t say how they hold their affiliates accountable for failing to follow that pledge. Nifla did not respond to written questions and declined requests for an interview. In a written statement, Heartbeat International, the largest pregnancy center network in the world, acknowledged that “it is important that medical professionals operate with licenses to help protect clients and patients from being harmed”, but it didn’t explain what it does to uphold its standards.

Meanwhile, mainstream women’s health providers say, ultrasound technology has proven to be especially susceptible to misuse and manipulation by pregnancy center staff. It’s common for patients to receive incorrect gestational ages, several doctors told Reveal.

“They’re trying to just run out the clock,” said Dr Nisha Verma, a Georgia OB-GYN who testified before Congress this summer on the impact of overturning Roe. “They tell people that they’re earlier so that they think that they have more time [to obtain an abortion]. And then people come to us. They’re like: ‘Oh my goodness. That is not what I was told. I was not told I was 15, 16, 17 weeks. I was told I was seven weeks.’”

How the supreme court thwarted attempts to force transparency

The issue of regulation is more urgent than ever in the post-Roe era. As abortion providers have shuttered in conservative states, pregnancy centers are trying to fill the gap in some core reproductive services. In areas that continue to allow abortion, centers are doubling down on efforts to deter women – many from out of state – from following through with plans to end their pregnancies.

Women’s health advocates have been especially concerned that sensitive health information collected by pregnancy centers could be weaponizedagainst abortion seekers. That’s because women are sometimes tricked into providing their personal information, as happened at the Women’s Help center in Jacksonville. And because most centers aren’t subject to the same privacy rules as medical clinics, advocates warn that information could be shared and used to harass or, in anti-abortion states, even prosecute patients, their family members and their abortion providers.

“In the current political environment,” said Lois Uttley, a senior adviser at Community Catalyst, a national healthcare advocacy group, “pregnant people need to be able to get care in a confidential manner and with assurance that it is the highest standard of care.”

But the supreme court’s 2018 decision in the California case presents monumental roadblocks for states and local jurisdictions seeking to protect women and hold centers accountable.

In 2015, California passed a law to protect low-income people who relied on the freebies pregnancy centers provide. The Reproductive Fact Act didn’t apply just to the state’s nearly 200 centers; it required any clinic “providing family planning or pregnancy-related services” to let clients know that the state also offered free or low-cost reproductive services, including abortion, and to notify clients if it wasn’t licensed to provide medical care. Pregnancy centers challenged the law, arguing that it infringed on their free speech rights.

California claimed it was seeking to regulate only “professional speech”, not religious or political speech. And reproductive rights advocates pointed out that many conservative states have laws that regulate what abortion providers can say. But the court’s conservative majority, led by Justice Clarence Thomas, rejected those arguments, ruling that the law violated the first amendment. The decision essentially freed crisis pregnancy centers and their employees from restrictions that apply in other medical contexts.

The ruling created huge new hurdles to passing laws protecting center clients, said Stephanie Toti, a constitutional lawyer who has argued reproductive rights cases before the supreme court. It “caused a lot of jurisdictions that would like to regulate pregnancy centers … to pause those efforts or move more slowly.”

Still, Connecticut lawmakers tried a different approach last year, passing a lawthat authorized the state’s attorney general to levy civil penalties against centers engaging in deceptive marketing. Three months after the statute took effect, a pregnancy center associated with Care Net, a faith-based network with 1,200 affiliates, sued in federal court to block enforcement, arguing that this legislation, too, infringes on religious liberty and free speech. The case is pending.

But the overturning of Roe is reviving interest in regulation, Toti said. This past summer, a group of US senators co-sponsored the Stop Anti-Abortion Disinformation Act, which would authorize the Federal Trade Commission to crack down on deceptive or misleading marketing practices at pregnancy centers. In November, the Los Angeles city council unanimously adopted an ordinance that allows the city to fine centers that falsely advertise their services and clients to sue if they have been misled. The law applies to any business offering pregnancy-related care.

Teneille Brown, the Utah law professor and bioethicist, said the California ruling is far more consequential than many people realize. “The supreme court has said that because they’re not only fake clinics, but religious and ideological ones, they can mislead consumers – something basic, non-ideological businesses cannot do,” she said. “They are not even required to correct the very confusion that they helped to create.”

Brown draws an analogy to the pandemic. Imagine going to a clinic that says it offers vaccines, she said: “They make it look like it’s a Covid clinic and they have signs outside saying ‘Covid vaccines here.’ You fill out a little clipboard, and someone who looks like a nurse comes out and they give you a shot.” But it turns out the clinic is run by anti-vaxxers who object to vaccines on religious and moral grounds. The staff isn’t licensed; the injection was nothing but sugar water.

Now, imagine if California passed a law forcing those clinics to let people know there are places where they could actually get a free vaccine. “And the supreme court says, ‘No, you can’t even do that. You’re not allowed to correct the misinformation where they think that they’re getting the Covid vaccine.’ ”

“That is just bananas,” Brown said. “In any other context, we would say you don’t get to do that … because you are defrauding people and that is putting their health at risk.”

This article was produced by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit investigative newsroom. Subscribe to their weekly newsletter to get new investigations directly in your inbox. Farah Eltohamy, Soraya Ferdman, Grace Oldham and Anya Syed contributed to this story.

Have you received services at a pregnancy center? Have you volunteered or worked at one? We’d like to hear your stories. Email reporter Laura C Morel: lmorel@revealnews.org.“

No comments:

Post a Comment