Murder, rape and abuse in Asia’s factories: the true price of fast fashion

"Jeyasre Kathiravel had always dreamed of a life beyond the garment factories of Dindigul, a remote corner of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

Despite the meagre wages she was earning – about £80 a month – Kathiravel knew she was lucky to have a job at Natchi Apparels, a local factory making clothes for H&M and other international brands.

Like many Dalit women in her community, a job at the factory had provided her family with a stable salary. Yet she wanted more. So, with dreams of escaping the deprivation and caste discrimination that had stalked her family for generations, the 20-year-old studied for the civil service exams by night before leaving her home each morning to work long shifts sewing clothes for other, luckier, young women thousands of miles away.

Kathiravel never escaped the factory floor. On 1 January 2021, she failed to return home from work. Despite her family’s frantic attempts to find her, four days later her decomposing body was discovered by farmers just a few miles from her village.

When her supervisor, a man named by Indian media as V Thangadurai, was arrested for her murder, few of her intimate circle were surprised. Thangadurai has since been charged with her murder and is in jail awaiting trial.

For months before Kathiravel’s death, her family and co-workers say that Thangadurai was perpetrating a relentless campaign of sexual harassment towards her, which she felt powerless to report or stop.

“She said this man was torturing her but she didn’t know what to do because she was so scared of losing her job,” says her mother, Muthuakshmi Kathiravel.

“She was such a good girl, she was the best of all of us. She was always helping me and supporting the family, but wanted to do different things with her life.”

Workers at Natchi interviewed by the Observer in the weeks after her murder say Thangadurai was known to be a sexual predator operating with impunity at the factory.

“We all knew what he was doing to Jeysare but nobody in management cared,” says one woman who worked alongside Kathiravel. “If she complained she was scared she would lose her job or that men from the factory would visit her family and say she was a troublemaker.”

A year later, Kathiravel’s family are still deep in grief. In their home, Kathiravel’s face smiles down at them from a photo on the wall and they say they can never fill the hole she has left behind. Yet they now believe her death has not been in vain.

In the weeks after her murder, dozens of other women working at the factory came forward to claim that they too were being harassed and assaulted at Natchi. Their bravery set off a chain of events that could transform the lives of the 3,000 women working at the factory and provide a blueprint for how global fashion brands can stop the epidemic of sexual violence that has taken hold in fast fashion supply chains.

The inexorable rise of the multi-billion pound fast fashion industry has conditioned consumers to expect rock-bottom prices and a constant churn of new products, ramping up the pressure brands place on their overseas suppliers to produce ever-higher volumes of clothing in less time – with garment workers on poverty wages facing the consequences on the factory floor.

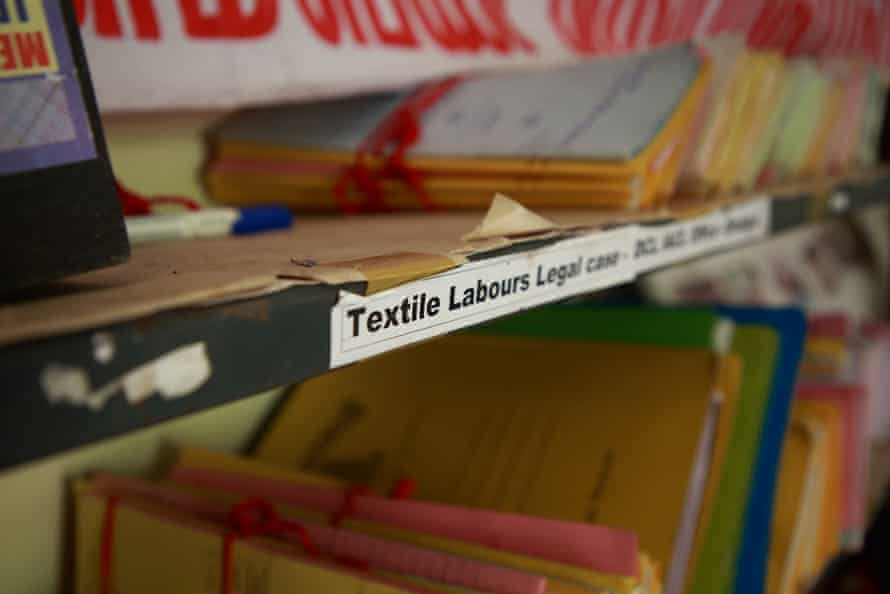

“The sexual harassment the women are facing in the garment industry is directly linked to their desperation to keep their jobs at all costs,” says Thivya Rakini, president of the Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union (TTCU). “Their fingerprints are all over the clothes that people in rich countries wear, but their suffering is being silenced.”

Despite the factory’s denials after the allegations were made public, the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), a global organisation investigating labour abuses, launched an independent investigation into Natchi.

Its findings, shared exclusively with the Observer ahead of publication by the WRC, are a grim read.

In a detailed report, investigators say that multiple interviews and evidence gathering with more than 60 workers led them to conclude that Kathiravel was not the first garment worker to have been murdered at Natchi.

Investigators say they are confident that at least two other female workers besides Kathiravel were killed while working at Natchi between 2019 and 2021.

The WRC says it is “virtually certain” that a company-contracted bus driver and labour recruiter murdered a female worker following a sexual relationship that began while they were both working at the factory.

The report claims there is a “high likelihood” that a migrant worker was also murdered on factory grounds by an unknown perpetrator and her body dumped in a shipping container. The report claims that multiple Natchi employees, including an eyewitness, testified that the murder had occurred on factory property and that afterwards managers had told workers not to talk about the incident.

The WRC has made it clear that investigators did not find concrete evidence to hold Natchi management directly responsible for these alleged killings or for the death of Kathiravel.

However, the report argues, multiple murders of female Natchi employees by men working for Natchi in supervisory or quasi-supervisory roles could not be detached from the environment of gender-based violence and harassment that Natchi management had allowed to flourish at the factory.

WRC investigators concluded that over the past decade, women working at Natchi had been subjected to “pervasive” physical sexual harassment, verbal sexual harassment, non-verbal sexual harassment and sexual coercion, with male supervisors propositioning female workers at the workplace for sexual relationships by coercive means.

Women workers told investigators that their male supervisors routinely bullied and publicly humiliated them for missing production targets and they were subjected to constant verbal abuse and sexual slurs. Investigators also found that factory management tolerated an environment of caste discrimination, where workers from the lowest Dalit castes were shunned by employees from higher castes.

Eastman Exports, which owns Natchi Apparels, says it “disputes the accuracy of a number of statements in the WRC report” and denies that the murder of a migrant worker occurred on Natchi premises.

However, the company says it has taken all the allegations seriously and “has created systems, processes and procedures to protect and promote the rights of female workers”.

“We have listened very carefully to our women workers and we are going to make sure that no woman ever feels unsafe again in one of our workplaces,” says Subash Tiwari, chief executive of Eastman Exports, who says he was shocked by the murder of Kathiravel and that his top priority was ensuring the safety of his female workers.

Last month, groundbreaking legally binding agreements were signed between Eastman Exports and the TTCU – a local female-led garment worker trade union that represents women at the factory – as well two international worker rights groups, the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) and Global Labor Justice-International Labor Rights Forum (GLJ-ILRF). Among other provisions, the agreement will overhaul the factory’s internal complaints process, install TTCU members on the factory floor to ensure women are safe at work and operate a zero-tolerance approach to harassment and verbal and physical abuse.

Despite cancelling its orders at Natchi, H&M has signed a separate agreement with the TTCU, AFWA and GLJ-ILRF and has committed to staying at the factory to help with implementation. It is the first time a brand has signed up to an initiative to tackle gender-based violence in Asia’s garment industry, where women make millions of tonnes of clothing for UK high streets every year.

If the agreement is properly implemented, the WRC says that Natchi could become one of the safest places for women to work in Tamil Nadu, a region notorious for dangerous working conditions for women.

“Our report documented serious abuses at this facility; however, because Natchi has made enforceable commitments to protect workers, it now presents a lower risk to buyers than just about any other supplier they might use,” says Rola Abimourched, deputy director of investigations and gender equity at the WRC.

Yet the labour rights groups involved in the Natchi case say the abuse that was uncovered should not be seen as an isolated incident. Instead, it is an indication of how sexual violence has flourished and become deeply embedded into the production model of fast fashion.

“What we are facing is an epidemic of gender-based violence in the global fashion industry, but because it is happening to poor women working thousands of miles away it isn’t considered the huge human rights scandal that it is,” says Abimourched.

In Tamil Nadu, the TTCU is investigating 29 other cases where women have died non-natural deaths while working in garment factories supplying brands sold in the UK. It says that in many cases, the women were murdered by male colleagues after alleged rapes and campaigns of sexual harassment.

“The abuse and harassment that was happening at Natchi is just everyday life in the factories where we work,” says Rakini. “We have seen many cases of women dying in garment factories across the region and nothing being done to investigate or seek justice.”

Anannya Bhattacharjee, international coordinator at the AFWA, says her organisation has catalogued multiple cases of egregious gender-based violence at garment facilities across Asia.

“Over the years, across production countries, we have witnessed and documented women garment workers being verbally and physically harassed, assaulted, threatened with retaliation for refusing sexual advances and denied basic rights,” she says.

Interviews with female workers by AFWA researchers in 2021 paint a horrifying picture of the scale and impunity of the sexual violence faced by the women who make our clothes.

“I have worked in this industry for more than 20 years and I have seen terrible things happen within these factories – rapes, suicides and even murders,” one woman working in a factory in India producing clothing for foreign brands told AFWA researchers.

“Women workers have no power to oppose the men in power – be it supervisors or managers. They can do anything to any woman – we are all at their mercy and we have no one to support or stand for us.”

Female workers in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka also spoke to AFWA researchers about similar conditions at their factories. They spoke of managers forcing women to take pills to delay their periods in order to meet production targets, male workers coercing women into sexual relationships to get their sewing machines fixed and women being fired if they complained about sexual harassment.

“We keep silent due to fear of losing our jobs … the mental stress reached the point of breakdown – I was feeling almost suicidal,” says one woman at a factory in Pakistan that the AFWA says was making clothing for multiple brands selling in the UK.

For years, campaigners have warned that the fashion industry’s use of ethical codes of conduct and factory inspections to flag up human rights abuses don’t work; instead they allow brands to swerve responsibility for abuses that their production model and profit margins have created.

In the weeks after Kathiravel’s murder, women workers at Natchi told the Observer that the factory inspections conducted by brands were a sham. “The management knows when the auditors are coming and they tell us what to say,” said one young woman. “They say if we complain the factory would close and we would lose our jobs.”

When abuses are uncovered, especially sexual violence, this allows brands to “cut and run”, pulling their business from suppliers and protecting their reputation.

“When trade unions raise issues of gender-based violence in a garment supplier factory to a brand, they generally just cut sourcing from that supplier. When they do this women lose jobs, are doubly victimised and become fearful of speaking out about what is happening to them,” says Bhattacharjee.

The WRC says that in the case of Natchi, brands that sourced from the factory had a moral responsibility to keep their business there.

“H&M has committed to support this vital programme to combat gender-based violence and harassment by signing the agreement. If H&M does not restore orders soon, it will gravely undermine the success of its own programme,” says Abimourched.

She also says that brands, including Marks & Spencer and Walmart, that were sourcing from the factory in the period of time when workers testified to experiencing sexual abuse had an obligation to resume orders.

“If they do not place orders now to support this process, it will be clear that their claims about respecting worker rights are meaningless.”

H&M says that while it had stopped orders at Natchi, “our focus and hope is that the agreement reached will contribute to sustainable and lasting change for the industry as a whole beyond one individual company”.

Marks & Spencer says it ceased trading with Natchi in January 2020 and will not be working with the factory nor signing up to the agreement.

“We have not sourced from Natchi Apparels for over two years and had ceased the relationship prior to the WRC investigation. Ethical trading is fundamental to how we do business and we fully support the principle of remediation to improve working conditions,” it said in a statement.

Walmart did not respond to a request for comment.

In Dindigul, the TTCU says it is working with women across the region who are now coming forward to ask for help.

“We are all human beings, all of our lives matter,” says Rakini. “We have to make sure that Jeysare’s death is the start of something that could prevent other women from also losing their lives because those in power simply don’t care.”

Sign up for Her Stage to hear directly from incredible women in the developing world on the issues that matter to them, delivered to your inbox monthly:

Sign up for Her Stage – please check your spam folder for the confirmation email

No comments:

Post a Comment