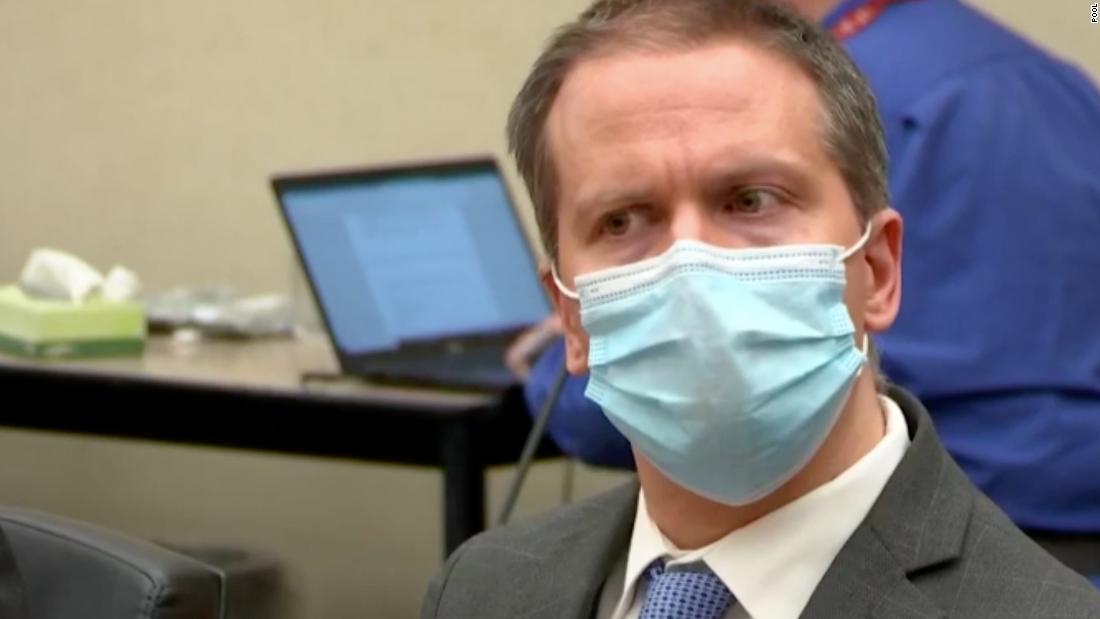

It was the look of indifference in Chauvin's eyes on May 25, 2020, as he casually drained the life out of George Floyd. That was as chilling as his knee on Floyd's neck. And what it represents could pose the biggest challenge to broader police reforms ahead.

That look was freeze-framed in what the prosecution dryly called "Exhibit 17." It shows Chauvin, the White Minneapolis police officer who was found guilty on all three counts in Floyd's death, glancing at a crowd of onlookers while bearing down on an unconscious Floyd, who is handcuffed and pinned face-first to the pavement.

The look on Chauvin's face is one of bored disinterest. His sunglasses are perched on his head and his hands rest in his pocket. He doesn't seem to notice Floyd at all. The only flicker of emotion on his face is his annoyance at the crowd that has gathered to plead for Floyd's life.

That will go down as one of the defining images of our era because it tells a story about racism that many people don't want to hear.

When we talk about racism, we often focus on spectacular acts of cruelty. The ghoulish

photo of Emmett Till's face in an open coffin. The

lynching postcardsthat some White Americans used to mail to one another. The

snarling faces of White students who surrounded a young Black woman who tried to integrate an Arkansas high school.

But the look of disinterest in Chauvin's eyes is a reminder that indifference -- not just hate -- is a critical part of how racism works.

The late Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate

Elie Wiesel once

said, "The opposite of love is not hate, it's indifference."

Wiesel

said that to the indifferent person, "his or her neighbor are of no consequence... Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the Other to an abstraction."

Why indifference can be more harmful than hatred

There is a peculiar pain to being ignored, to not even being seen. Most Black people have experienced this. That's why if you talk about racism to some in unguarded moments, you'll hear something strange.

Some find it

easier to deal with the open hatred of overt racists when compared to those White people who don't even see them. At least the racists recognize that they exist -- they see them, even if their vision is clouded by hate.

To not be seen is another, more insidious variant of racism that can be infuriating. Perhaps that's why one of the best novels about racism by a Black author is titled "

Invisible Man."

And that's why it's no accident that it was White indifference -- not hatred -- that seemed to

anger the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. the most.

King didn't write his epic "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in 1963 in response to the hateful actions of White segregationists. He addressed it to a group of White moderates who he thought were indifferent to the suffering of Black people living under segregation, and who were "more devoted to order than to justice."

Racism needs indifference like a plant needs water and sunlight.

White indifference is

why slavery and Jim Crow lasted so long.

White

indifference to police brutality is why so many Black men continue to die like Floyd.

White indifference is why

it's harder for Black and brown people to vote in some states than for White people.

It's White indifference that

allows so many Black and brown students to go to racially segregated public schools with fewer resources. It's White indifference that

allows so many people in the medical profession to believe that Black people don't feel pain like others.

Indifference makes Black pain invisible -- just as it did with Floyd.

Violent acts of White racism grab the headlines. But the most pervasive forms of racism take root when White judges, cops, politicians and ordinary people look the other way to not see what is happening right in front of their faces.

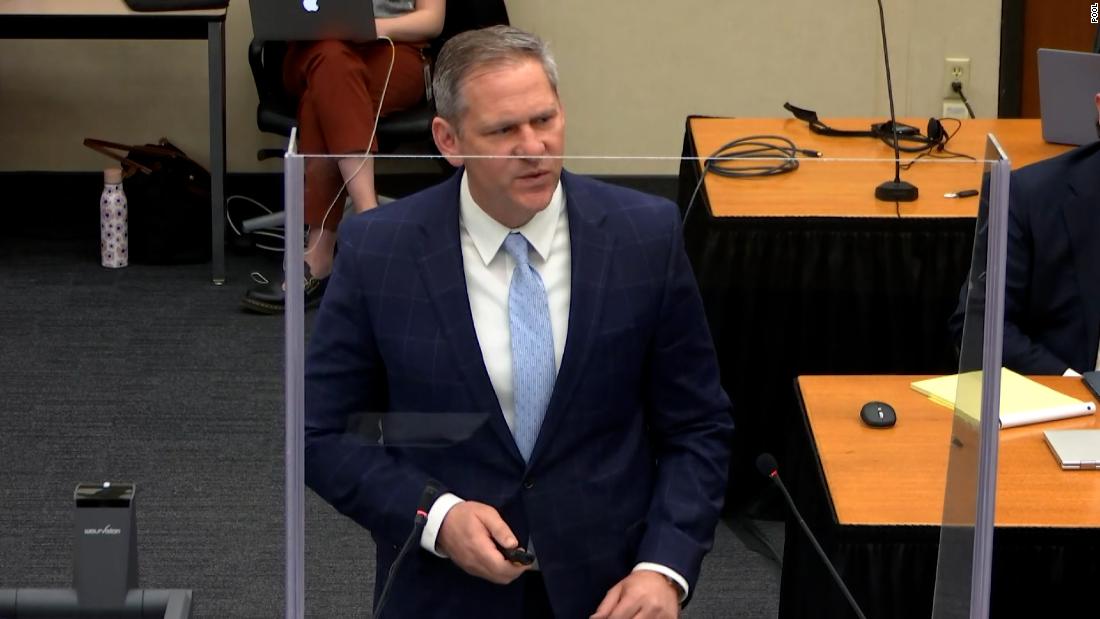

Prosecutors used Chauvin's indifference against him

It's hard, though, to dramatize White indifference. Photos of indifference don't go viral.

But then Chauvin came along. And the prosecutors at his trial recognized that it was his indifference, not just his cruelty, that was a big part of why Floyd died.

They

focused relentlessly on Chauvin's casual body language during his arrest of Floyd and the lack of concern on his face as he pinned Floyd to the ground. They told jurors Chauvin showed "

indifference" to Floyd's pleas for help. They said Chauvin and other officers at the scene talked about the smell of Floyd's feet and

idly picked stones from a vehicle's tire while Floyd died in front of them.

The prosecutors built a case where they forced the jury to see Floyd as a human being and not as an abstraction.

"There was no superhuman strength that day. There was no superhuman strength because there is no such thing as a superhuman," prosecutor Steve Schleicher

said in his closing arguments. "...Just a human, just a man lying on the pavement being pressed upon, desperately crying out. A grown man, crying out for his mother."

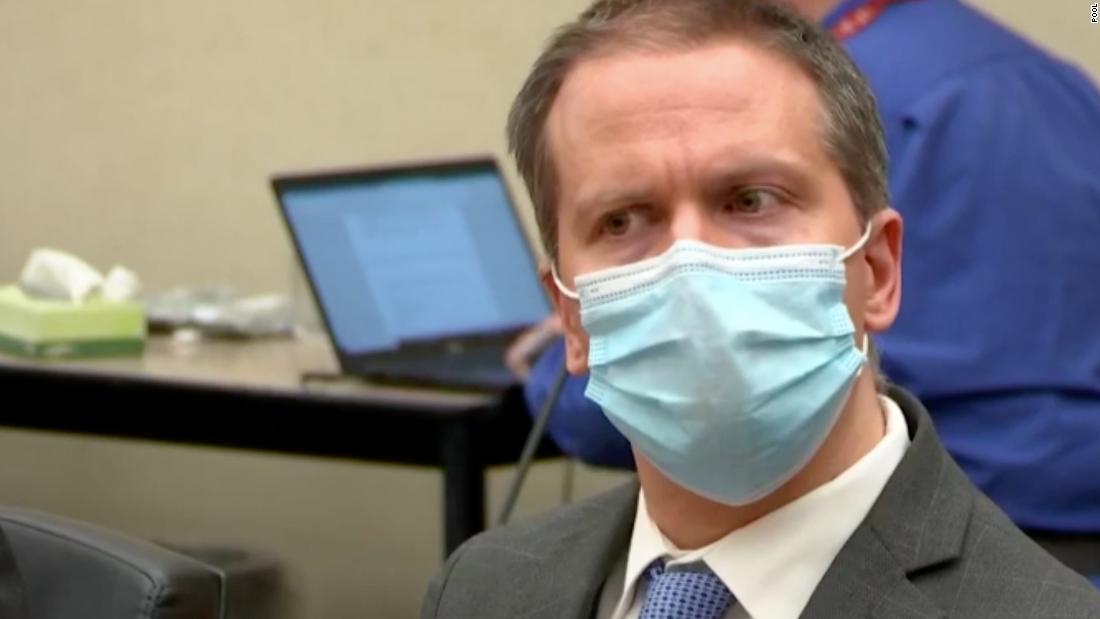

There was one moment, however, when Chauvin's look of indifference broke.

It came at the end of his trial, when the judge read the guilty verdict. Chauvin's eyes darted about in panic. They widened in disbelief. And maybe in that moment, as he was handcuffed and led away, he got a glimpse of the terror that so many Black and brown men have felt.

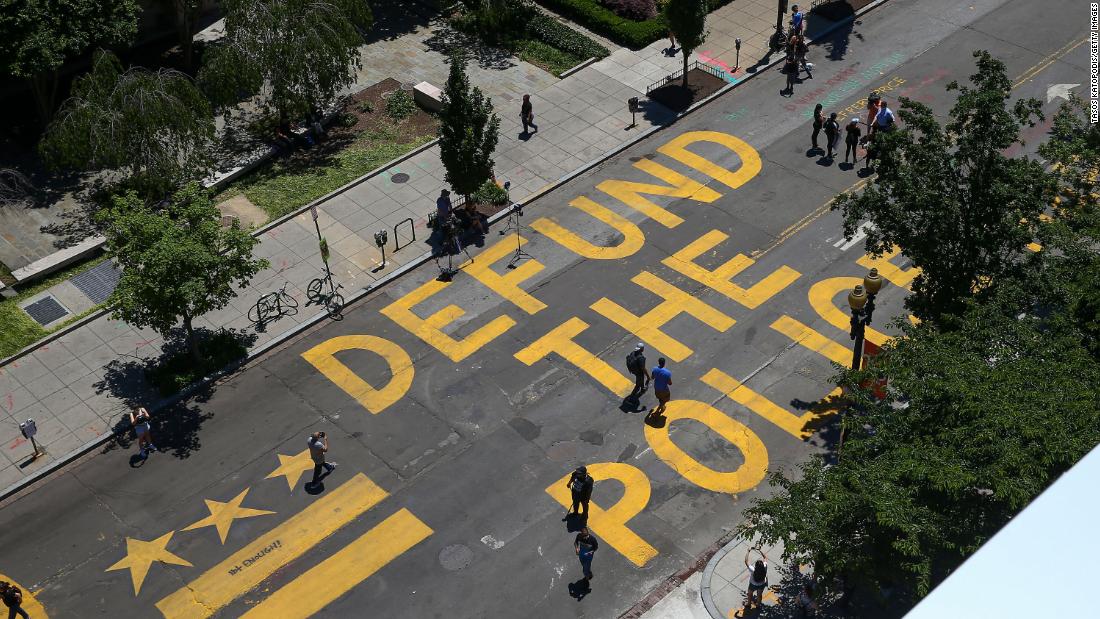

Why this indifference poses a challenge for the future

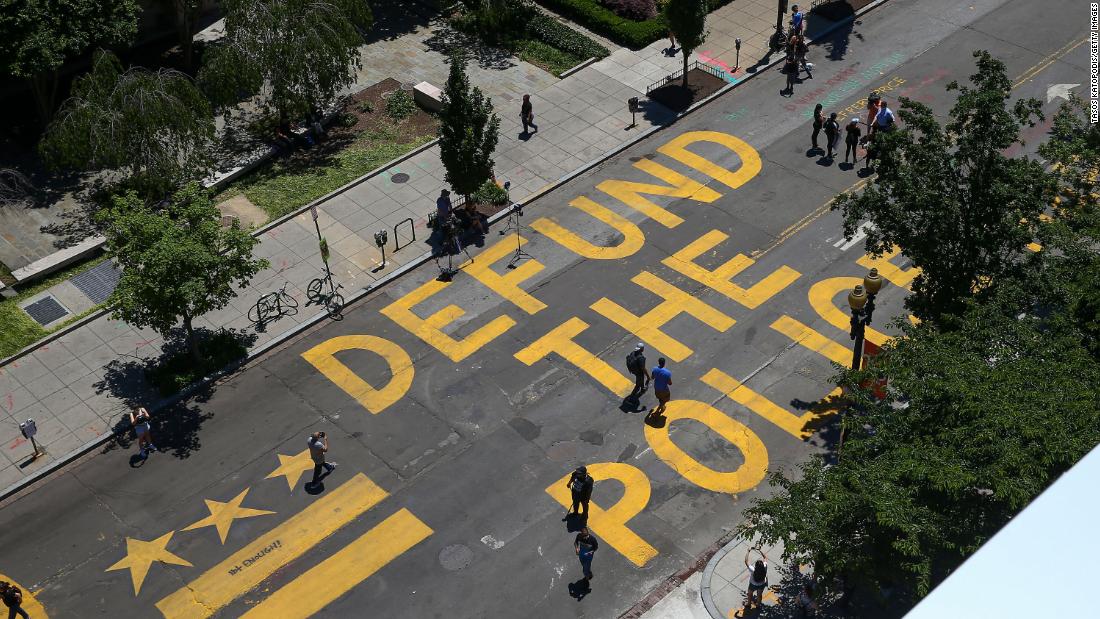

As activists use momentum from the Floyd verdict to press for more police reforms, this wall of indifference may be their biggest challenge. There are plenty of complicated proposals to reform policing: a federal ban on chokeholds and no-knock warrants, challenging authorities' immunity from civil suits and stopping the militarization of local police.

Much of the progress on police reform, though, will boil down to this: Will enough lawmakers and judges see Black and brown people who are being brutalized by the justice system as fellow human beings? Or will some they continue to see them as thugs, predators, or superhuman?

History suggests that this will be a huge challenge, because the resiliency of White indifference is often underestimated. Its strength is in its anonymity -- it doesn't typically call attention to itself, and its perpetrators are often unaware that they see certain people as the Other.

In his

book, "Race in the Mind of America: Breaking the Vicious Circle Between Blacks and Whites," psychologist Paul L. Wachtel

wrote that what is often called racism can be more precisely described as indifference.

"Perhaps no other feature of White attitudes... is as cumulatively responsible for the pain and privation experienced by our nation's Black minority at this point in our history as is indifference," he wrote. "And at the same time, perhaps no feature is as misunderstood or overlooked."

Perhaps

Exhibit 17 of the Chauvin trial will change that.

Many people can't muster the strength to watch the entire Floyd video. It's just too painful. But plenty of people saw that image of Chauvin looking bored as a Black man's life ebbed away beneath him.

As activists press for more changes in the wake of the verdict, Chauvin's face could serve as a sober reminder.

Indifference -- not hate -- may be the biggest obstacle to police reform.”

No comments:

Post a Comment