Living With Karens

A white woman calls the police on her Black neighbors. Six months later, they still share a property line.

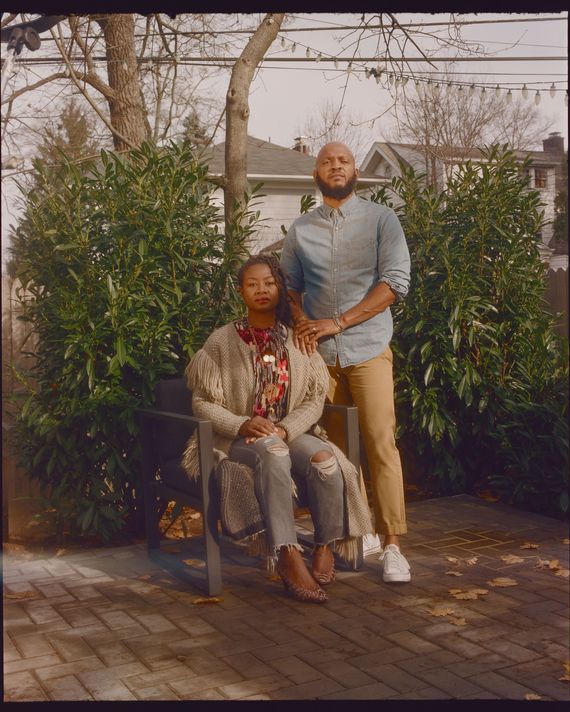

Norrinda Brown Hayat and Fareed Hayat on their patio. Photo: Photograph by Kendall Bessent for New York Magazine

When it came time to relocate from near D.C. to the New York tristate area, Fareed Hayat thought, I’m certainly going to Brooklyn. It was the summer of 2017. He and his wife, Norrinda Brown Hayat, had both gotten new jobs — he would be teaching criminal law at CUNY, and she had taken a position as the director of the Civil Justice Clinic at Rutgers — and Fareed had dreams of brownstones fueled by a viewing of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It reboot on Netflix. They considered whether the city could be a suitable substitute for their suburban existence in Maryland, but while looking at homes with their two young sons, the eldest, Kingston, kept asking questions like “Where is the other floor to the house?” and “Are all of the houses just on top of each other?” “He was so extra,” Fareed said.

A few of Norrinda’s new colleagues lived in Montclair, New Jersey, and suggested she look there. Here’s the brochure copy: Only 40 minutes from New York by train. Not suburban, but “urban suburban.” An art museum there recently hosted a Kara Walker exhibit. Stephen Colbert is on the board of the annual film festival and still lives in town. Oh, and did you hear the rumor about the swinger parties? Parts of it are very affluent — Upper Montclair has been ranked as the wealthiest community in New Jersey. It leans heavily Democratic and has great restaurants, great public schools, a young Black mayor, and a really cute pie shop. And the kicker: Montclair is 24 percent Black.

Well, technically, the latest Census estimate has it at 22.3 percent Black, but ask a real-estate agent, a town resident, and a politician what’s unique about Montclair and eventually they’ll all trot out that 24 percent figure. For Montclair, diversity is a matter of local pride. New Yorkers could move there and find they wouldn’t have to sacrifice the reasons they had chosen to live in a city in the first place. In 2019, the New York Post wrote, “Montclair is the only suburb true New Yorkers will even consider.” Brooklynites move there with such regularity it has been called “Park Slope with backyards,” along with other epithets that are equally insufferable. To set a Zillow alert to Montclair (versus, say, Glen Ridge, a nearby suburb with comparable median property values but a significantly more homogeneous, white population) is to actively choose diversity and progressiveness in addition to that manicured lawn and the driveway with space for two cars. It is choosing to adopt what some residents half-jokingly call the “Kumbaya” Montclair mentality.

Fareed and Norrinda, who are now both 43, settled into a six-bedroom house in Upper Montclair. Norrinda recalled, “One of my colleagues, their high-school daughter was like, ‘You know, you really live in the whitest part of town,’ because young people just say whatever’s on their mind. I’m just like, ‘Look. It’s very competitive to land a house. You just have to go where you land,’ ” which for them was Norman Road, where, one day in late summer, I met Fareed as he was unloading groceries from the trunk of his Tesla. After he delivered a fresh bouquet of sunflowers to his wife inside, we set off on a walking tour of their part of town. He pointed out a great mid-century-modern furniture store, Modclair, and a coffee shop, where we got chocolate croissants. We darted past masked patrons waiting in socially distant lines at farmers’-market booths before settling down in a sprawling park.

When they had first moved in, Fareed researched paint colors on Pinterest and decided he wanted his house to be black. He wanted something stylish, not “cookie cutter” — and he liked the idea of “the only Black family on the block in a black house,” he explained. (Norrinda objected. They settled on more of a charcoal with black trim.) But their private joke on suburban Black exceptionalism didn’t quite hold up on Norman Road. They weren’t the only family of color on the block. There were several interracial families. Corner to corner, there was diversity of age, race, and sexuality, unified by self-selection. “The diversity was the biggest thing,” Fareed said. “You know, 24 percent African American population here in Montclair.” They sent their sons to a public Montessori school that has a Black principal, and both boys have four or five Black teachers. It’s been over two years of block parties, PTA meetings, dinners, and birthday gatherings, of making friends and stitching themselves into the community. Norrinda was made president of the PTA for this school year.

As we walked, I noticed that everyone, white, Black, whatever, gave us a nod as we passed. Of course, no town is perfect; there were some things, some experiences, some people, that had bothered them, explained Fareed. But then he told me a story meant to illustrate just how much being a Black family in Upper Montclair wasn’t a thing. One day, he was out fixing some uneven concrete on the sidewalk in front of his house. A white woman, a neighbor, stopped to ask about the work he was doing. At the end of their conversation, she said, “You remind me so much of my ex-husband.” Fareed assumed the husband was Black, but no — her husband was white. A Black man had reminded a white woman of her white ex-husband. Imagine that! Well, in Montclair, you could.

Recently, though, after the incident in June when a video Fareed had posted of an altercation with a white neighbor went viral, he was thinking about the time he spent in the Caribbean. It’s where he did his study-abroad program when he was a college student at UCLA studying history. He remembered the joy he felt at being surrounded by Black people. The cops there didn’t have guns. He rarely felt like the other. He didn’t feel out of place.

It’s not that he felt that out of place in Montclair. He knew what it meant to feel really, truly out of place in his neighborhood, he said. He’d been out of place when he first moved from L.A. to Silver Spring to go to law school at Howard University. Before deciding to pursue law, he had done well investing in properties in L.A., enough that he could buy a home with a pool for himself and his brothers and nephews. Yet he felt under suspicion from the moment he parked his Range Rover in the driveway. “It was always a question of legitimacy,” he said. But here in Montclair, their moving truck was met by cupcakes dropped off by a white man, who chatted him up about the schools. “You know, this space is a creation,” Fareed said. “White people come to this space to be around a diverse space. So I recognize that, and I don’t feel out of place in that way.”

He knows you have to be able to fulfill certain economic requirements to pay off a mortgage and the insanely high property taxes in these areas of Montclair. If you can do that, it makes you a certain kind of acceptable, which isn’t to say the cupcakes-bearing white neighbor wouldn’t have been as welcoming if the Hayats weren’t two accomplished lawyers. “There’s been a lot of intentionality about creating a space that’s welcoming to a person like myself economically and education-wise,” Fareed said.

But since that altercation with a white neighbor, he has been on a half-serious campaign to convince his wife that — since school was remote anyhow, and their jobs were remote anyhow — didn’t it sound nice to just rent a two-bedroom apartment in Barbados or St. Lucia or South Africa? To ride out the pandemic in a place where he didn’t feel like his Blackness was the center of the conversation, where he didn’t have that consciousness every single moment? Where he wasn’t just part of the 24 percent.

Susan Schulz, caught on video by Norrinda Brown Hayat during the incident in June. Photo: FAREED NASSOR HAYAT/FACEBOOK

The incident on Marion Road, as people call it now, even though it occurred on Norman Road, happened in late June during that pileup of stressors: COVID and the peak of the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests in response to the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Like many in a financial position to do so, the Hayats, realizing they would be home all summer, had decided to make a few upgrades to their yard and started work on a stone patio out back. It was a weekday. Their two boys had just gotten home from forest camp and were inside having lunch, while their parents remote-worked in different parts of the house. The landscaper and her crew were outside planting a garden and installing the new patio.

Susan Schulz, a neighbor who lived one street over on Marion, approached the landscaper. Schulz’s and the Hayats’ properties are separated by a wooden fence, ’90s-sitcom style. They could have popped their heads over it to share a quick conversation, had they been friendly enough to do so. Schulz noticed work being done in the neighboring yard and went to investigate. She approached the landscaper with such deliberateness that the landscaper assumed she was going to ask for a business card. Instead, Schulz began to inquire about the work being done: What was being built? Did the Hayats have a permit? Was this a patio? Can this be done without approval from the city?

Norrinda was standing on the porch on a call and heard Schulz outside. It was the second time she had come by that day. Norrinda sighed, paused her work, and leaned out to tell Schulz she would speak to her when she was off the phone. Schulz left and came back again with the same question: Did they have a permit for this work? She left and came back three times in under an hour, according to several people on-site that day. “Let me go because my neighbor’s trying to talk to me, and she’s a firecracker,” Norrinda said to her colleague.

She went to talk to Schulz and dispatched Fareed to tell the landscaper it was okay to keep working. When Fareed got outside, Schulz was interrogating his wife.

“At this point, Norrinda is becoming more offended,” Fareed recalled. The questions from Schulz — did you get a permit? Will you stop working until you have one? — were becoming more aggressive. It’s legal in Montclair to build an unraised patio in your own backyard without a permit. Still, they went back and forth, back and forth, about a permit that nobody needed. Schulz also accused the Hayat children of throwing balls into her yard. Eventually, Fareed had had enough.

“At a certain point, I’m not being friendly over here,” he recalled. To Schulz, he raised his voice: “You know what, you should just leave.”

But Schulz refused. “I’m not going anywhere,” she said, according to Fareed. He repeated his request. Again she refused.

It was then that a handful of neighbors started to come out of their houses to see what was going on. One white neighbor, who was passing by on her daily walk, heard Fareed saying, “I’m asking you to please leave our property.” “He was really polite, but there was an urging,” she said. “That’s when I felt like something might be really wrong.” She decided to stick around with the others. The landscaper put down her work and joined them.

The already heated talk began to escalate into an actual shouting match. Fareed became more adamant that Schulz get off his property, and Schulz began walking backward down the driveway. She lost one of her flip-flops. She noticed the neighbors watching. She stood in the middle of the street as the argument continued. Then Schulz pulled out her phone and called 911, and Norrinda pulled out hers and started recording.

“I’m calling the police,” she said.

“Okay, we expect that of Amys,” Norrinda can be heard saying, her voice shaking. “Of course you are.”

While on the phone, Schulz paced in a circle. She approached a neighbor on the sidewalk, perhaps looking for someone to corroborate her story, perhaps just looking for sympathy. “Did you just see him physically push me?” she yelled.

“Oh, he absolutely didn’t push her,” reported the neighbor who had walked by. “I think she was looking to me — honestly, it did feel like a look of incredulity. Can you believe what he’s saying to me? I understand she was upset, but that’s just an insane trope that goes back so many hundreds of years of white women saying that Black men are assaulting them. And it was just really unbelievable she thought she would get away with that with witnesses.”

Over the phone, Schulz told the police, “I need an officer … the gentleman who is taller than me pushed me off his property.”

Neighbors began to yell things like “Shame on you” and “In this climate, you’re doing this?” while Schulz continued her defense, sometimes to the neighbors, sometimes to Norrinda and Fareed. “He pushed me ten feet … I came over here alone. I should have brought my son … Are you gonna say you didn’t put your hands on me?”

“It was like, Yo, this woman really believes what she’s saying,” Fareed recounted. “I feel like, in her mind, she really did start believing that she was assaulted. Maybe she was affronted by being told no. But for her, that affront was synonymous with me physically assaulting her. There was no difference in her mind.”

Norrinda began to plead with her husband, “So our kids don’t have to see the police, please just go inside with them.”

Schulz walked over to a neighbor across the street. “Look at my arm,” she said, holding up her forearm. She turned to Norrinda. “Can you please stop recording?”

“This is for the people so they can see,” Norrinda replied. “Even in Montclair, this is what we are living with.”

We rarely see what happens after the STOP button is hit. That day, the cluster of Norman Road neighbors stood waiting, wondering what would happen when the cops actually arrived. Some of them exchanged information just in case — of what? Not sure, but it felt like the right thing to do.

“Who was that person?” the neighbors wondered. She didn’t live on their street. “Which house is it? Who came over to yell?” someone asked. Someone pointed to Schulz’s house, where she lives with her partner and kids. Someone else chimed in, “Oh, we know her. She’s the beer-pong mom. She lets her high-schoolers have parties in the backyard past curfew.”

Within ten minutes, three cars from the Montclair Police Department showed up. Two stayed. They spoke with Schulz first and the Hayats next, moving to the backyard for a private conversation. Then they left. Later, the deputy chief, Wilhelm Young, released a statement in which he called it a “dispute between neighbors” and revealed that neither party had filed a police report.

Many of the neighbors I spoke to in the months following the incident didn’t know Susan Schulz well. There was the beer-pong-mom rumor. Someone reported seeing her at a block party once or at a soccer game years ago. She lived a block over, so people on Norman Road didn’t know her. Her kids were older, so she wasn’t part of the main social fabric of her stretch of the block. Was she a Republican? Didn’t she harass the previous renters, a multi-racial family who eventually moved? It was as if she were the Boo Radley of Upper Montclair. Except it was worse: She was their Karen.

Was there anything worse to be called in the summer of 2020 than a Karen? (Well, yes, but if you were white, apparently not.) An internet term for a complaining white woman who is caught weaponizing her racial privilege, a Karen calls the cops on a person of color for something she perceives to be offensive. Sometimes she exaggerates the situation, sometimes she flat-out lies. The stories Karens tell the police, the world, and themselves go unchallenged because the women are white. There has been much debate about whether the term is sexist — there’s no direct male equivalent, and its meaning has been so diluted that it often seems synonymous with “bitch” or “woman who has an opinion I don’t like.” There has also been debate about whether the term is racist against white people and if you can even be racist against white people. But for all the discourse, there is general agreement that you don’t want to be labeled a #Karen. Because while the hashtag makes it lighthearted enough, it’s rooted in white supremacy and the history of Black people getting killed because of it.

The heightened racial tension of the summer resulted in an extreme sensitivity for those white people who were only now learning about Karens and weren’t quite sure if they had ever been Karen-y. Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist and Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism sold out on Amazon, and local small Black-owned bookshops were overwhelmed with orders for the tomes of anti-racist reading. “How to help Black Lives Matter” and “How to donate to Black Lives Matter” were among the top Google searches of 2020 in the U.S. Black people who knew white people in any capacity at all became anti-Karen tutors, exhausted by the questions and the light-bulb-on revelations of liberal white people considering, perhaps for the first time, the nuances of systemic racism. Suddenly, it was clear, you weren’t immune from having been racist if you voted for Obama or had one Black friend or even more than one Black friend.

Only a month before Marion Road, a woman named Amy Cooper, a.k.a. Central Park Karen, had called the police on a Black man named Christian Cooper, who recorded the incident. The video went viral, but, in a rarely seen twist, Amy Cooper was held accountable for her actions. She lost her job at an investment firm, and the animal shelter from which she had adopted her dog briefly took it back. She now faces criminal charges, and New York State legislation was passed in direct response to the incident. Maybe it was because she faced consequences both personally and legally that this Karen made a lot of white people stare into the mirror and wonder if a Karen stared back. It also changed something about the way many Black people saw social media as a tool for racial redress — for the first time in American history, they could ask to speak to the manager too.

That night, Fareed watched the video from that afternoon. He watched the wild-haired woman shouting at him, watched the way she went to each of the white neighbors and held up her arm as invisible physical proof that Fareed had allegedly pushed her. And at each attempt, she was rejected: by white people.

“I thought the video just captured the moment,” he said. “Not even speaking about our moment, but it fulfilled all of the benchmarks of what we have been talking about in the community in terms of the Karen phenomenon. In terms of calling upon the power of the state to suppress Blackness. What many of the other videos don’t capture or don’t demonstrate is the white rejection of that. I thought it actually coalesced into an amazing teachable moment. It was like a play.”

After he watched it, Fareed posted the video to his Facebook page with a lengthy message: “It has happened again,” he began, before launching into a detailed account of the incident, including a careful, passionate explanation of how Schulz had “invoked centuries of brutality in her call to the police and sought to put her black neighbors back in their place.” He ended the post with a declaration: “Her type, the racist, must be rejected and ostracized like she was today by Norrinda and I, but equally important, by our white neighbors here in Montclair and our white and non-white allies worldwide.” He named her Permit Karen.

Views began percolating almost immediately. Over on the Secret Montclair Facebook group, the moderator decided to break the “no shaming videos” rule because she felt it necessary that people see what had happened in their own community. Comments overwhelmingly supported the Hayats (“I’m so sorry this happened to this family,” “Shame on you Susan!”). The owners of a local gelato shop banned Schulz from entering and told her to “move to Florida where you belong.” A few fights broke out regarding public shaming, which quickly turned into shaming a woman who had called out shaming. There was a lot of admiration for the white neighbors (“Shout out to the white allies!”), some innocent discussions of “What is a Karen?” and “Why Karen, not Permit Patty?” that devolved into some nastiness, and several gripes from people named Karen who hoped to distance themselves from the “Karen” characteristics. Many comments registered shock at this happening in Montclair, and many registered no shock at this happening in Montclair, because Montclair is in America.

The Hayats’ across-the-street neighbor Lisa Korn has lived on the block for six years and in Montclair for 28, relocating here from Chelsea because she really didn’t “want to live in a lily-white all-Christian suburb.” She was on the street the day of the incident and, as Schulz approaches, can be heard yelling, “Don’t you come near me without a mask!”

“Norrinda just broke my heart,” Korn said of her conversations with the Hayats in the immediate aftermath. “She said, ‘I just didn’t think in this town — we moved here because of this town. Because we thought it would be safe.’ And I said to her, ‘It is safe, Norrinda. This is not the norm here,’ ” she said emphatically. “ ‘This is not who we are.’ ”

Neighbors like Korn weren’t blind to Montclair’s problems. As often as they list the ways they are proud of their town, Montclarions can recite the ways in which, “of course, the town is not perfect.” The wealthier communities are segregated from the non-wealthy ones. There is an achievement gap in schools they speak of often. They have formed countless committees to address things like why there aren’t more students of color in AP classes. Then there was the local NAACP meeting about Montclair policing at which the cops displayed a thin-blue-line flag, a symbol associated with Blue Lives Matter, and everyone was outraged.

There are also subtler ways in which the Black experience in Montclair is fundamentally different, ways Black Montclarions experience race and racism their white neighbors probably aren’t aware of, ways that can’t be mass-addressed with town halls or seminars or marches or anti-racist reading lists supplied by the Montclair library. Both Christina Joseph Robinson and her husband are from Black families that have lived in Montclair for decades. It’s a town she feels comfortable in as a Black woman. “But you still have to kind of hunt out where the Black people are,” she said. “You know, historically, in the Fourth Ward there are more Black people than there are in other sections of town. Everywhere else, you might be the only one on your block, you know? I’m sure there’s people that probably have never even been to certain parts of town or that may not know where the good Caribbean-food spot is or the hair-braiding spots. ‘Oh, I never even knew that was there.’ I hear that all the time.”

Which is why I was so surprised that Norrinda had expressed such a level of incredulity in that conversation with her neighbor. In addition to being a Black woman, her whole career is dedicated to thinking, writing, and teaching about race in our culture. And yet over email, she told me that, yes, she too had been blindsided by Schulz. “I should not have been, but I was,” she wrote, sounding almost sheepish.

Norrinda grew up in a Black middle-class area of Philadelphia that she describes as “really supportive and full and communal and [with] a lot of Black businesses.” She had white friends at school, but her family didn’t know their parents or interact with them on weekends. “They went back to their world, and me to mine.” It’s different for her kids, who “live, go to Cub Scouts with, have parties with, and travel with a diverse group. And they have since preschool.”

“I am not opining on which is better,” she added. “I think there is good to be had in both scenarios.” But they chose Montclair because it was a community that would allow her children to have this specific upbringing, maybe even with the underlying hope that they could grow up there without ever having a run-in with a Karen.

The day of the Schulz interaction, Norrinda and Fareed’s two boys had been watching from a window. The couple had to explain the situation but avoided going into great detail. They didn’t want a single incident to affect how comfortable and happy their children felt in their community.

“More than anything, we tried to downplay it with them,” explained Fareed. “I certainly tried to talk about how this neighbor was misinformed and made a bad decision, not really talking about the larger institutional implications of what motivated her to do that … really just trying to make her out to be just a bad actor as opposed to a part of a system. I wanted them to know they were in a safe space.” Yes, they had talks with their children about race and racism and the history of systemic racism, Fareed said, but this was different. This was the kind of consciousness that could upend the way they saw themselves in their own world.

The residents of Montclair applied the same sort of logic to the Hayats in general. They wanted them to know that Schulz was just one bad actor; it wasn’t the whole Montclair system. One Karen didn’t spoil the whole town. “What it was, it was a galvanization,” said Korn. “We galvanized around them because I think we had to.”

Perhaps because the video was so reminiscent of the Amy Cooper–Christian Cooper incident, Montclair residents were quick to see it as a rare chance to both talk the talk and walk the walk. Karen doesn’t get to be an invisible figure. You find out where she works, where she lives. You call for her to be fired. You call for her to be run out of town. You call for her to be arrested. As people started to sleuth out and post details of her identity, there was some confusion about which Susan of Marion Road it was, as Lorraine Agostinelli, who lived down the block from Schulz, noticed when she went to watch the video on Facebook that night.

“I commented, ‘That’s not the Susan you think it is!’ We have about five Susans on this street!” she said. Eventually, the commenters got it right: her position at the EPA, her address. The next day, after the video had lived on Facebook for less than 24 hours, a handful of high-school students rang the Hayats’ doorbell. “They were the most respectful, you know, ‘Mr. Hayat,’ and they were socially distant,” Fareed said with a laugh. “They said, ‘We’re just letting you know we’re organizing a protest, and we’re going to tell her she must go.’ ”

That afternoon, some 60 residents, mostly denim-shorts-clad teens from Montclair High, started marching up and down Marion Road chanting “Hey, hey! Ho, ho! Your racist self has got to go!” They hoisted signs that read BLACK LIVES MATTER and WHITE ENTITLEMENT IS VIOLENCE. They marched back and forth for about five or ten minutes, according to Diego Goldfrank, 17, who had helped his three friends get the word out about the march. People came out to watch and film. “It was very moving,” recalled one neighbor. “But it’s not a very long block.”

A portion of the group wound up in front of Schulz’s house, where they wrote BLACK LIVES MATTER and #NOTHERE in chalk on the asphalt for another 15 or 20 minutes. The cops came just as it was already dying down. Goldfrank said police told them someone had reported that people had thrown a brick at her house. (They did not, said Goldfrank.) It was peaceful and small and, of course, captured by iPhones and reporters and even by Schulz, who stood on the sidewalk recording the protesters with her phone.

The story became local news, then national news when TMZ covered it. The Hayats felt compelled to make a statement from their driveway to a group of reporters. Standing in front of their charcoal-gray house, they formed a perfect portrait: two hip, well-dressed young Black professionals and parents — not that it should matter, but of course it did.

As attention grew, a cop car was posted outside the Hayats’ house and another outside Schulz’s to monitor the situation. BLACK LIVES MATTER signs propagated on neighborhood lawns. Even some of the white neighbors picked up in the video became local celebrities, recognized by passersby who wanted them to recount what had happened.

A June protest went by Schulz’s house in Montclair. Schulz, in blue, stood watching. Photo: Chanda Hall.

Norrinda maintains it was never her intention for her video to go viral. It wasn’t even her intention to share it at all. “I took that video because my family was at risk. I don’t desire visibility in that way at all. I study race; I don’t want to be the subject of my own studies. And I find that to be a conflict professionally for me,” she explained.

But there was a certain kind of visibility Norrinda was seeking — not national attention but the relief of Now you can all finally see what we’ve been dealing with. There’s a beat in the video when Norrinda can be heard saying in a wavering, frustrated voice, “She’s been waiting two years to do this to us.” The video was proof of this moment, yes, but also proof of many moments that people never saw, moments the Hayats weren’t even sure they had seen themselves.

The run-ins had started as soon as they moved in. When the Hayats were painting the house their carefully selected not-quite-black color, Schulz made comments about their choice, said Fareed. “Why would you paint a rental house?” she asked. And, you know, it was possible she had assumed they were renting because the house was a rental for a number of years before they bought it. But why even ask the question? There was a small thought in Fareed’s mind that perhaps she wouldn’t have asked a question with such an obvious answer — we painted it because we own it — of a white family.

Some months later, once they had settled in, Fareed wanted to re-create the tree house his children had had in their yard in Maryland. He hired someone to disassemble the tree house, plank by plank, and drive it up to Montclair so he could rebuild it, plank by plank, in the big tree in their new yard. While he was building it, Fareed recounted, Schulz asked questions like “Isn’t that dangerous for children?” And she told them the tree house actually hung over into her property. Fareed went so far as to move the tree house again to make sure it was clearly in his yard. And when he put up lights outside to decorate for Norrinda’s 42nd-birthday party, Schulz inquired if the lights would stay up. He wasn’t sure why it was her concern. These were the only kinds of conversations they ever had.

There’s no way to really prove the interactions were racially motivated. But there was something in the tone that the Hayats recognized, something that was uncomfortable to explain to outsiders, uncomfortable even for them to fully admit to themselves. The interactions were reminiscent of ones Fareed has had his whole life, from those neighbors in Maryland who arched their eyebrows at his homeownership, all the way back to the time he was thrown in jail for a night because a cop falsely reported that Fareed had assaulted him. (That was the incident that made him want to go to law school.) There was a sense of entitlement in the way Schulz asked the questions. A sense that, if she asked, they had to answer. And they had answered, every time, for the sake of keeping the peace. They would let it slide and then they would let it slide again, but now it was June 2020. The world was crazier. The woman was crazier. People were paying attention. It was no longer possible — or necessary — to let it slide.

For a while, it was the gossip on Facebook groups, neighborhood email chains, and the local streets. It helped that there wasn’t much else to do over the summer besides walk dogs and talk to the neighbors you saw on these walks. The family became the center of mostly positive, but sort of uncomfortable, attention. The doorbell would ring, and someone — maybe from the neighborhood, maybe from the surrounding town — would drop off a basket of cookies or a bottle of wine as if offering their condolences. They were sent heartfelt apologies and declarations of support written on greeting cards and personal stationery decorated with ornate blue-and-white flowers or carefully typed up and printed on computer paper like a school report. “We promised a Black friend we would speak up,” began one letter. A woman in Portland, Oregon, wrote to say she was appalled and offered to send a letter to Schulz, too. (She enclosed a copy of what she intended to say.) The owner of one of the more popular restaurants in town offered them a discount whenever they wanted to come in and said Schulz was no longer welcome.

At the monthly town-council meeting, reduced to a Zoom because of COVID, at least four residents — talking over users who had forgotten to mute themselves and the constant be-bop-boop-boop of people joining the call — spoke of how disturbed they were by the incident, how ugly it all was, and how disappointed they were; most important, they insisted that something be done. Couldn’t an ordinance be passed making false 911 calls illegal? Couldn’t they find a way to punish Karen/Susan?

Town representatives explained multiple times that a New Jersey state law already criminalized false 911 calls, but it didn’t address racial bias the way the New York State law did. A few days later, Dr. Renee Baskerville, a former Montclair councilwoman from the Fourth Ward, wrote an impassioned op-ed for a local website, Baristanet, again encouraging the town to take legal action in the Marion Road matter. Town leaders should look to New York, she wrote, where Amy Cooper had been successfully charged. They should explore legal action against Schulz, perhaps involving the Department of Justice if necessary.

Through all of this, Susan Schulz didn’t speak. She didn’t respond to multiple requests to speak for this story. Her friends and people in her circle all declined to speak too. One neighbor refused because she saw the situation only as a property dispute, but mostly she just wanted it to go away. Another friend, who is close to Schulz, wanted to make sure I read comments on Patch.com that supported Schulz and blamed the Hayats. (One was written by a Black woman named Karen who was mostly mad that “Karen” was being used as a slur; another, written by a “Lisa K” — not Lisa Korn — called the Hayats rude and unfriendly and said there are no white supremacists in the neighborhood.)

Agostinelli, who lives on the same block as Schulz, provided the most information anyone seemed to have on her. “I’ve had pleasant conversations with them. They’re not offensive people,” she said of Schulz and her partner, Theresa. “I think there’s a lot of soul-searching that’s going on in that house, I’m assuming.”

One night around 9:30 p.m., shortly after the encounter, the Hayats’ doorbell rang. It was a friend of Schulz’s delivering an apology letter on her behalf. “She said she now understands how calling the police could have become a much bigger deal,” Fareed recalled. “That’s the best she could give. That she shouldn’t have done it because she understands how it could become a bigger deal. She never acknowledged anything else beyond that. She did indicate that she wanted to move forward peaceably and that we wouldn’t have any additional problems. She’s stood by that.”

Schulz didn’t come to the block parties and didn’t join the socially distant neighborhood toast the night Joe Biden won, when everyone came out into their yards and hoisted glasses of booze together because finally the country was going to change. Some of the rumors that had circulated about Schulz turned out to be overblown or at least more ambiguous than had been suggested. The multiracial family who lived in the house years ago, the ones she had supposedly harassed, recalled a single interaction in the time they lived there. They had never spoken to her, but one day the husband was trimming a tree in the yard and stacked the branches at the border of the property. Schulz rang their bell and requested that they remove the logs because they were touching her fence. There was no greeting, they recalled, and it felt unusual and not friendly. And that was it.

But the less she spoke, the more she became a synecdoche for all of racism. She was Permit Karen. In that letter the woman from Portland wanted to send to Schulz, she wrote, among some other insults and admonishments, “I don’t know what happened to you to make you this way.”

There was something I recognized in those letters the Hayats received. That same summer, every white person I knew offered to march alongside me at rallies. I got texts from “Maybe: Susanna,” a person I didn’t really remember, dredging up a racial transgression I definitely didn’t remember. Borrowing the newly learned language of anti-racism, she apologized for any micro-aggression she had committed and apologized for making it my responsibility to explain HBCUs to her. I wrote back and told her “no sweat.” (It later turned out she had confused me with another Black colleague.) She was one of many who reached out to ask how they could be a good ally and wondered if there were times they hadn’t been. My phone was constantly buzzing with texts from white friends apologizing, checking on my well-being, offering me Venmo reparations and sympathy and empathy. I was appreciative but wary. They said they wanted to know about my experiences, but mostly they wanted to feel they had acknowledged that I’d had experiences with racism that they might have ignored, without exposure to all the grisly details.

In talking to Fareed, I often felt he was holding two opposing thoughts in his mind: relief that he lives in this intentional community that discusses race, that embraces the 24 percent, and loneliness at being at the center of a conversation in which everyone sees you and no one does. There can be an oppressiveness to sympathy, a way in which a newly galvanized community doesn’t let in room for doubt — for wondering whether the community would have been quite so galvanized if it hadn’t been the peak of a summer of racial-justice protests, if you still had locs or a shitty car in your driveway, or didn’t have a law degree, or your wife wasn’t the president of the PTA. When everyone is working so hard, when everyone is so vocally on your side, so apologetic for your experience, it’s easier to accept “Kumbaya” Montclair than to wrestle with those questions and ask other people to wrestle with them too.

In August, New Jersey governor Phil Murphy signed a bill criminalizing false police reports that are used as a form of racism or bias intimidation. Around that time, the Montclair Police Department approached the Hayat family and asked them to give a statement. The Essex County prosecutor was considering bringing criminal charges against Schulz.

Nobody really discusses the incident on Marion Road anymore, and people seem to be relieved to move on. “People remember that house on Marquette as the ‘Russian-spy place’ because the family that inspired The Americans lived there,” Agostinelli told me on the phone one day when I asked her if this has changed the neighborhood. “But I don’t know if people are going to remember Marion Road as ‘Oh, that’s where the Karen was.’ We had three houses that just flipped on our street.” By August, a Facebook commenter was asking, “Whatever happened to this?” By September 22, the moderator begged on a post, “Can we stop with the dumb Karen comments?” By October, when the Hayats took me to the backyard and showed me the patio, some BLM signs had been removed in favor of Halloween decorations.

Yes, the patio. It was small and manicured, a ten-by-ten-foot rectangle in their sizable yard, just big enough to hold a few nice chairs around a coffee table and firepit. They had recently put in three tall shrubs that blocked the view of Schulz’s yard.

“It’s the smallest patio anyone’s ever seen,” said Norrinda when we sat down. “I really wish it was bigger, at this point, because everybody in the world wanted to see it. People would be like, ‘We’re going to come hang out on your patio … Oh.’ It’s too much. They’re like, ‘Oh, it’s cute.’ ”

Ah, yes, I joked, the patio that started all the conversation.

“It shouldn’t have started any conversation,” Norrinda replied. The Hayats spent most of the summer hoping the conversation would die out, if she was being honest. In the end, they didn’t write back to the people vowing to curse Schulz on their behalf; they didn’t take that discount at the restaurant. They chose not to cooperate with the prosecutor. “Personally, I think if [Schulz] had been prosecuted and found guilty in any way, even just paid a $500 fine, I think this would have gone away for her a lot faster,” suggested a Montclair resident who had tracked the situation.

“I find it embarrassing, the entire ordeal,” Norrinda emailed me one night. “Didn’t Toni Morrison say, ‘The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.’ I should be grading papers right now, but I am writing you.” That was the rub. “What is Susan doing right now? Not this. Not explaining herself six months later. We didn’t press charges because then we become the wrongdoer. We don’t believe in the criminal legal system. We believe in restorative practice. I would be happy if she moved. It would not make me happy if she was in jail.”

Fareed posed a question in one of our talks: “White supremacy that’s alive and well and a part of all of us,” he said, “and the question is, How much of it are we going to reject? And how much are we willing to sacrifice ourselves in order to continue to move forward?” He asked it from an intellectual distance, as if he were delivering closing arguments or posing a question to his class. But at close range, the question simply is, Would my neighbors step up to defend me again? And will they continue to want to have this conversation about race now that the immediate drama is over?

It’s a partial yes. Norrinda recently passed the baton as chair of the anti-racism group that is part of the PTA. Now it’s run by a white person. The last time I spoke to Fareed on the phone, on a weeknight in December, he was multitasking, trying to rally his son into a just-drawn bath while facilitating an online conversation for his anti-racist film group. That night, the group was watching America to Me, a documentary about institutional racism in a town similar to Montclair. “A majority in the group are white women,” he told me. “People are participating more and are attempting to do something about it.”

As for Schulz, Norrinda thought she once saw her in the grocery store. Fareed told their boys they needed to be careful with the balls in the yard. He doesn’t want things to escalate. They finally have peace. Everyone wants it to stay that way.

But sometimes, well, often, when he’s standing in his house, looking out over the fence, he sees Schulz in her yard, or even just the empty yard, and it hits him. Just for an instant. Maybe it was silly or naïve or too optimistic, but there was an expectation that in Montclair he could be aware of the reality of being Black in America without having to confront it or acknowledge it in his daily life. But now, “we do actively acknowledge it,” he said. “It’s just a reminder of that reality.”

No comments:

Post a Comment