Americans seeking to renounce their citizenship are stuck with it for now

"As many as 30,000 citizens living abroad have been unable to secure a ‘loss of nationality’ interview during the pandemic

In recent years, Michael has come to regard the United States, the nation of which he has been a citizen all his life, as an abusive parent.

“I can acknowledge my past association with that person while at the same time wanting to keep future association to a minimum,” he said.

Michael – the name is false as he requested anonymity to avoid being inundated with hate mail – found his disaffection with his native country reach crunch point in 2020. The chaotic end of the Donald Trump era combined with the inequities exposed by the Covid pandemic made him despair of being an American.

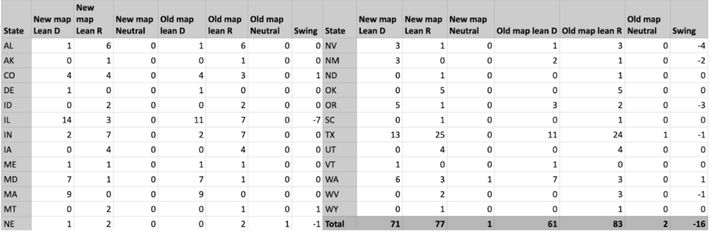

“Coronavirus made me realize that in the US, if you’re not a member of the moneyed elite you’re left to fend for yourself with virtually no help from the federal government,” he said. “The farcical presidential campaign made me realize that I don’t want to be a member of a society in which my vote is made irrelevant by gerrymandering or the electoral college.”

And so Michael decided to renounce his US citizenship. Having moved to Finland 10 years ago, he would break the ties that officially bound him to a country whose values he no longer recognised.

That’s when Michael’s troubles really began. He discovered that along with thousands of other US citizens living abroad, he was caught in a Kafkaesque trap.

For almost two years, since the pandemic struck in March 2020, most US consular missions around the world have suspended their expatriation services for those wishing to give up US citizenship. The US embassy in London, the largest of its sort in western Europe, announces on its website that it is “currently unable to accept appointments for loss of nationality applications” and is unable to say when services will resume.

The US state department says giving up citizenship requires a face-to-face interview with a government official, and that it is too risky given coronavirus.

Delays have led to a growing mountain of disgruntled citizens. By some calculations, there may be as many as 30,000 people among the 9 million US citizens living abroad who would like to begin the renunciation process but can’t.

Joshua Grant is one of them. He was born and raised in Selma, Alabama, until he moved to Germany when he was 21 to learn the language.

He has been there ever since. He lives in Lower Saxony and married a German citizen last year. Grant, 30, feels ready to acquire German citizenship, but under German law he must let go of his US passport. Easier said than done.

He submitted a pile of paperwork to the US embassy in July 2020. Nothing has happened. He has written emails to the embassy staff, with no reply.

He contacted the office of US senator from Alabama Richard Shelby. They passed him on to the state department, which in turn passed him back to the bureau of consular affairs, which mentioned the pandemic.

“It’s very taxing. My whole life in Germany is on hold,” he said. “It’s funny: people in Germany tend to see the US as a liberal country where the rule of law was established, but I can’t even find anyone in the US government to talk to.”

Nine US citizens abroad who have found themselves unable to give up their nationality are now suing the state department in a federal court in Washington. The suit, brought on the plaintiffs’ behalf by the French-based group Association of Accidental Americans, likens the situation to feudal times.

“The US appears intent on preventing its citizens from exercising their natural and fundamental right to voluntarily renounce their citizenship,” it says.

Some people want to give up US citizenship because the government has been making the burden of being an American more onerous for those abroad. In 2010 the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) was passed, requiring foreign banks and other financial institutions to report on any clients they suspect of being American to the IRS.

The US is also one of only two countries (the other is Eritrea) that tax people on their citizenship rather than where they live. That forces Americans abroad to declare their global income to the IRS, with possible tax implications.

The impact of these burdens is reflected in the number of people who renounce each year. Between 2000 and 2010 it remained relatively steady at less than 1,000 people, but after FATCA came in, the numbers rose sharply to a peak last year of almost 7,000.

Some of the would-be renouncers are “accidental Americans”, having acquired citizenship because they were born in the US though they have lived elsewhere all their lives.

That label could be applied to the UK prime minister Boris Johnson, who was born in New York but has not lived in the US since he was five. Johnson renounced his citizenship in 2017, having said he was outraged a few years earlier by having to pay the US tax authorities for gains on the sale of his London home.

Marie Sock, the first woman to stand as a presidential candidate in the Gambia, was forced to pull out of the race recently after she failed to get any response to her request to renounce her US nationality from the US embassy.

She explained in a video posted on Facebook that under Gambia election law, presidential candidates must be sole Gambian nationals.

James – also not his real name – was born in Texas but has not lived in the US since he was four. He now lives in Singapore.

He became disillusioned when he learned that because his son was born outside the US he would not be eligible for US citizenship, and yet because of James’s citizenship he would treated as if he were a US taxpayer. That struck him as a modern form of taxation without representation.

“The double standards really annoy me,” he said.

For the past year he has been trying to get through to an official who will help him renounce his citizenship, without success.

“I never asked for US citizenship, and now I’m not even allowed to give it up.”