I publish an "Editorial and Opinion Blog", Editorial and Opinion. My News Blog is @ News . I have a Jazz Blog @ Jazz and a Technology Blog @ Technology. My domain is Armwood.Com @ Armwood.Com.

What To Do When You're Stopped By Police - The ACLU & Elon James White

Know Anyone Who Thinks Racial Profiling Is Exaggerated? Watch This, And Tell Me When Your Jaw Drops.

This video clearly demonstrates how racist America is as a country and how far we have to go to become a country that is civilized and actually values equal justice. We must not rest until this goal is achieved. I do not want my great grandchildren to live in a country like we have today. I wish for them to live in a country where differences of race and culture are not ignored but valued as a part of what makes America great.

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Monday, June 29, 2020

Governor extends public health emergency, COVID-19 guidelines

Governor extends public health emergency, COVID-19 guidelines

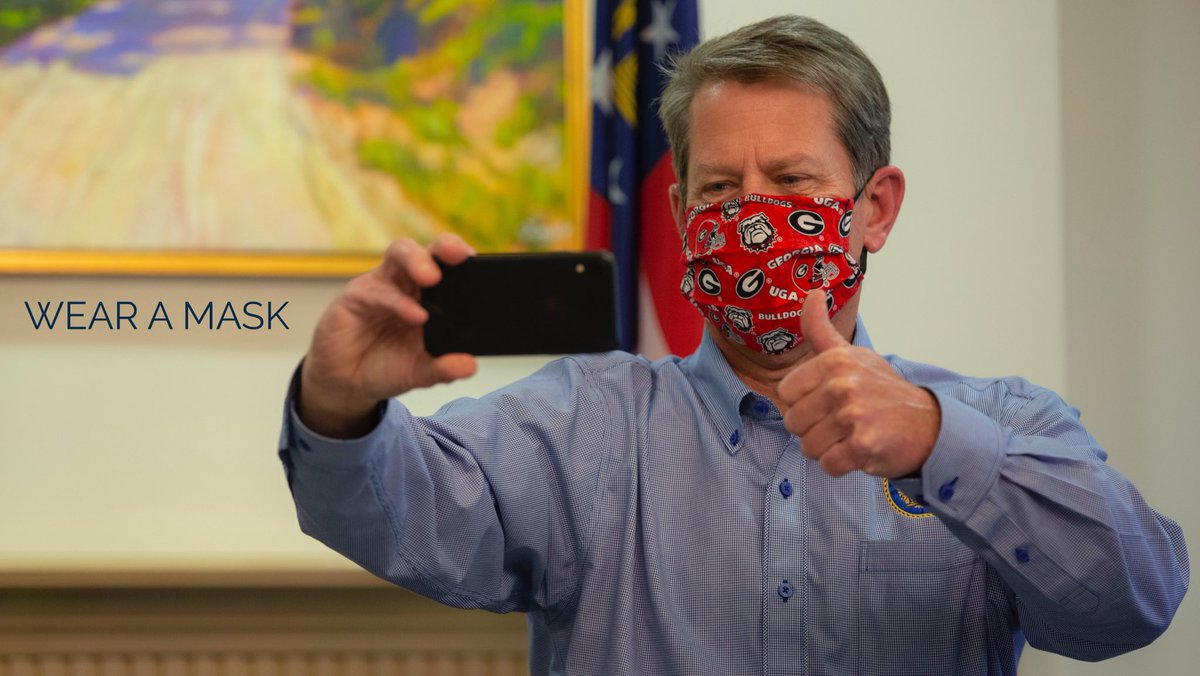

ATLANTA — Gov. Brian Kemp has issued a new executive order extending the state’s public health emergency over COVID-19.

Kemp said in a news release Monday that the new order extends the emergency until August 11, 2020.

“As we continue our fight against COVID-19 in Georgia, it is vital that Georgians continue to heed public health guidance by wearing a mask, washing their hands regularly, and practicing social distancing,” Kemp said. “While we continue to see a decreasing case fatality rate, expanded testing, and adequate hospital surge capacity, in recent days, Georgia has seen an increase in new cases reported and current hospitalizations.”

The governor has also extended social distancing guidelines until July 15.

“Executive Order 06.29.20.02 continues to require social distancing, bans gatherings of more than fifty people unless there is six feet between each person, outlines mandatory criteria for businesses, and requires sheltering in place for those living in long-term care facilities and the medically fragile,” Kemp said. “The order also outlines that the State Board of Education must provide ‘rules, regulations, and guidance for the operation of public elementary and secondary schools for local boards of education’ in accordance with guidance the Department of Public Health.”

The latest numbers from the Georgia Department of Public Health show there are 79,417 confirmed cases in Georgia.

As of Monday, 1,359 people have been hospitalized because of the virus and 2,784 people have died from the coronavirus across the state.

The current executive order allows live event venues like the Fox Theater to reopen.

The Fox told Channel 2 investigative reporter Justin Gray that they’ll be staying closed for now. The Cobb Galleria Center said it plans to open for business again July 13.

But the Atlanta Convention Visitors Bureau told Gray that conventions, for the most part, are still off.

“In the short term when you have a risk that you are going to have a meeting and not many people are going to show up, I think meeting planners have decided to focus on 2021,” said William Pate, head of the Atlanta Convention Visitors Bureau.

As Georgia continues to roll back COVID-19 restrictions, Georgia State University public health professor Dr. Harry Heiman said with the increase in COVID-19 cases, the governor should be doing the opposite.

“For a public health person it’s very disturbing because I know where this story goes,” Heiman said. “The data is very clear that we’re moving in the wrong direction and without strong policy action on the part of our political and public health leaders, it’s going to go from bad to worse.”

Kemp remains against rules requiring people to wear masks or face coverings.

“There’s some people that don’t want to wear a mask and I’m sensitive to that,” Kemp said.

But the governor is launching a new push to encourage face masks.

He tweeted on Monday, “Wear a mask, practice social distancing, wash your hands.”

Kemp plans to travel to towns across the state this week, such as Albany, Dalton and Savannah, to encourage Georgians to wear face masks.

This week the state will also distribute three million cloth facial coverings to local governments and schools.

Six Flags White Water reopens after COVID-19 closure for months

Three Words. 70 Cases. The Tragic History of ‘I Can’t Breathe.’ The deaths of Eric Garner in New York and George Floyd in Minnesota created national outrage over the use of deadly police restraints. There were many others you didn’t hear about.

Three Words. 70 Cases. The Tragic History of ‘I Can’t Breathe.’

The deaths of Eric Garner in New York and George Floyd in Minnesota created national outrage over the use of deadly police restraints. There were many others you didn’t hear about.

By Mike Baker, Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Manny Fernandez and Michael LaForgia

By Mike Baker, Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Manny Fernandez and Michael LaForgia

June 29, 2020

“Please. I can’t breathe. I can’t relax. You gotta take this mask off, dude. Please.”

“I can’t take it off, sir. I’m sorry.”

“Please. I already told you earlier, I have [expletive] problems, dude.”

“That’s what the medication is for. It’s gonna help calm you down.”

“All right, well, I can’t chill like this. Please take it off, take it off. Aww man, dude. Dude, please take it off, take it off, take it off!”

“Please take the mask off! I cannot breathe. Please.”

James Brown died in custody on July 15, 2012.

“Willie. Willie. Stop!”

[mumbles]

“No, sir.”

“I can’t breathe.”

“OK.”

“I can’t breathe!”

“You can breathe.”

“If you’re talkin’, you’re breathin’. I don’t want to hear it.”

Willie Ray Banks died in custody on Dec. 29, 2011.

“Get cuffs, I got his hands. Get cuffs. Get cuffs.”

“I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”

“Yeah, ’cause you’re [expletive] tired of running.”

“OK, I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”

“We’re on VC-71. Code 4. Lift the red. One in custody.”

“I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”

Byron Williams died in custody on Sept. 5, 2019.

As the sun began to rise on a sweltering summer morning in Las Vegas last year, a police officer spotted Byron Williams bicycling along a road west of downtown.

The bike did not have a light on it, so officers flipped on their siren and shouted for him to stop. Mr. Williams fled through a vacant lot and over a wall before complying with orders to drop face down in the dirt, where officers used their hands and knees to pin him down. “I can’t breathe,” he gasped. He repeated it 17 times before he later lapsed into unconsciousness and died.

Eric Garner, another black man, had said the same three anguished words in 2014 after a police officer who had stopped him for selling untaxed cigarettes held him in a chokehold on a New York sidewalk. “I can’t breathe,” George Floyd pleaded in May, appealing to the Minneapolis police officer who responded to reports of a phony $20 bill and planted a knee in the back of his neck until his life had slipped away.

Mr. Floyd’s dying words have prompted a national outcry over law enforcement’s deadly toll on African-American people, and they have united much of the country in a sense of outrage that a police officer would not heed a man’s appeal for something as basic as air.

But while the cases of Mr. Garner and Mr. Floyd shocked the nation, dozens of other incidents with a remarkable common denominator have gone widely unacknowledged. Over the past decade, The New York Times found, at least 70 people have died in law enforcement custody after saying the same words — “I can’t breathe.” The dead ranged in age from 19 to 65. The majority of them had been stopped or held over nonviolent infractions, 911 calls about suspicious behavior, or concerns about their mental health. More than half were black.

Dozens of videos, court documents, autopsies and police reports reviewed in these cases — involving a range of people who died in confrontations with officers on the street, in local jails or in their homes — show a pattern of aggressive tactics that ignored prevailing safety precautions while embracing dubious science that suggested that people pleading for air do not need urgent intervention.

In some of the “I can’t breathe” cases, officers restrained detainees by the neck, hogtied them, Tased them multiple times or covered their heads with mesh hoods designed to prevent spitting or biting. Most frequently, officers pushed them face down on the ground and held them prone with their body weight.

Not all of the cases involved police restraints. Some were deaths that occurred after detainees’ protests that they could not breathe — perhaps because of a medical problem or drug intoxication — were discounted or ignored. Some people pleaded for hours for help before they died.

Among those who died after declaring “I can’t breathe” were a chemical engineer in Mississippi, a former real estate agent in California, a meat salesman in Florida and a drummer at a church in Washington State. One was an active-duty soldier who had survived two tours in Iraq. One was a registered nurse. One was a doctor.

In nearly half of the cases The Times reviewed, the people who died after being restrained, including Mr. Williams, were already at risk as a result of drug intoxication. Others were having a mental health episode or medical issues such as pneumonia or heart failure. Some of them presented a significant challenge to officers, fleeing or fighting.

Departments across the United States have banned some of the most dangerous restraint techniques, such as hogtying, and restricted the use of others, including chokeholds, to only the most extreme circumstances — those moments when officers are in fear for their lives. They have for years warned officers about the risks of moves such as facedown compression holds. But the restraints continue to be used as a result of poor training, gaps in policies or the reality that officers sometimes struggle with people who fight hard and threaten to overpower them.

Many of the cases suggest a widespread belief that persists in departments across the country that a person being detained who says “I can’t breathe” is lying or exaggerating, even if multiple officers are using pressure to restrain the person. Police officers, who for generations have been taught that a person who can talk can also breathe, regularly cited that bit of conventional wisdom to dismiss complaints of arrestees who were dying in front of them, records and interviews show.

That dubious claim was photocopied and posted on a bulletin board at the Montgomery County Jail in Dayton, Ohio, in 2018. “If you can talk then you obviously can [expletive] breathe,” the sign said.

Federal officials have long warned about factors that can cause suffocations in custody, and for the past five years, a federal law has required local police agencies to report all in-custody deaths to the Justice Department or face the loss of federal law enforcement funding.

But the Justice Department, under both President Barack Obama and President Trump, has been slow to enforce the law, the agency’s inspector general found in a 2018 report. Though there has been only scattershot reporting by departments, not a single dollar has been withheld.

Autopsies have repeatedly identified links between the actions of officers and the deaths of detainees who struggled for air, even when other medical issues such as heart disease and drug use were contributing or primary factors. But government investigations often found that the detainees were acting erratically or aggressively and that the officers were therefore justified in their actions.

Only a small fraction of officers have faced criminal charges, and almost none have been convicted.

In the case of Mr. Williams in Las Vegas last year, Police Department investigators determined that the officers did not violate the law. But the death triggered immediate changes, said Lt. Erik Lloyd of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department’s force investigations team.

Officers are not medical doctors and may believe that someone who says “I can’t breathe” may be trying to escape, he said.

To alleviate potential dangers, officers are told now to promptly get detainees off their stomachs and onto their sides — or up to a sitting or standing position. They are also told to call for medical help if someone has distressed breathing.

“Since the death of Mr. Williams, our department has been extremely aware of someone saying, ‘I can’t breathe,’” Lieutenant Lloyd said. “We have changed the attitude of patrol officers.”

For the relatives of many of the men and women who died under similar circumstances in police custody, watching the video of Mr. Floyd’s arrest in Minneapolis has felt painfully familiar. Silvia Soto’s husband, Marshall Miles, died in 2018 in Sacramento County, Calif., after being pinned down by sheriff’s deputies at a jail. She said she had been feeling both heartbroken and comforted amid the national outrage.

“I don’t feel alone anymore,” Ms. Soto said.

‘You want to kill me?’

While there have been dozens of “I can’t breathe” deaths over the past decade, the emergence of body cameras and surveillance footage has eliminated the invisibility that once shrouded many of these deaths.

Videos from Mr. Garner’s death galvanized changes in neck restraint policies around the country, but problematic techniques for restraining people did not go away. In the six years since then, more than 40 people have died after warning, “I can’t breathe.”

Less than three months after Mr. Garner died, police officers went out to a tidy stucco home near Glendale, Ariz., to investigate a report of a couple arguing.

The officers found Balantine Mbegbu seated in a leather chair with his dinner. Both Mr. Mbegbu and his wife assured them that no argument had taken place. According to police reports, Mr. Mbegbu became indignant when they refused to leave.

“Why are you guys here?” he said, his voice rising. “You want to kill me?”

When he tried to stand, the officers slammed him to the floor, punched him in the head and shot him with a Taser. With Mr. Mbegbu on his stomach, officers put knees on his back and neck.

As his wife, Ngozi Mbegbu, watched them pile on top of her husband, she heard him say, “I can’t breathe. I’m dying,” according to a sworn statement she made. Records show he vomited, began foaming at the mouth, stopped breathing and was pronounced dead.

The county prosecutor’s office determined that “the officers did not commit any act that warrants criminal prosecution.”

Cases in which detainees protested that they could not breathe, before dying, continued to occur. Their words could be heard on audio or video recordings, or were otherwise documented in official witness statements or reports.

In 2015, Calvon Reid died in Coconut Creek, Fla., after officers fired 10 shots at him with a Taser.

In 2016, Fermin Vincent Valenzuela was asphyxiated after police officers in Anaheim, Calif., put him in a neck hold while trying to arrest him. His family won a $13 million jury verdict.

In 2017, Hector Arreola died in Columbus, Ga., after officers forced him to the ground, cuffed his hands behind him and leaned on his back, with one officer brushing off his complaints: “He’s fine,” he said.

In 2018, Cristobal Solano was arrested in Tustin, Calif., and then died after at least seven deputies worked together to subdue him on the floor of a holding cell, some with their knees on his back.

In 2019, Vicente Villela died in an Albuquerque jail after telling guards who were holding him down with their knees that he could not breathe. “Right, because they’re having to hold you down,” one of the guards said.

Matthew Vance

Then last week, the Police Department in Tucson, Ariz., released video of an encounter on April 21 with Carlos Ingram Lopez, who was naked and behaving erratically when officers forced him to lie face down on the floor of a garage with his hands handcuffed behind his back. Part of the time, Mr. Lopez’s head was covered with a blanket and a hood. He was held down for 12 minutes, crying for air, for water and for his grandmother. Then he, too, died.

‘If you can talk you can breathe’

One of the reasons such cases keep occurring may be the persistent belief on the part of police officers that a detainee who is complaining that he cannot breathe is breathing enough to talk.

Edward Flynn, the former police chief in Milwaukee, said in a deposition in 2014 that this idea was once part of training for officers there and persisted as a “common understanding” even if it was wrong. Other departments have told their officers the same thing, records show, and the notion shows up often in interactions with detainees.

“If you’re talking, you’re breathing — I don’t want to hear it,” a sheriff’s deputy told Willie Ray Banks, who was struggling for air after officers in Granite Shoals, Texas, restrained and Tased him in 2011.

But the medical facts are more complicated. While it may technically be true that someone speaking is passing air through the windpipe, Dr. Carl Wigren, an independent pathologist, said that even someone able to mutter a phrase such as “I can’t breathe” may not be able to take the full breaths needed to take in sufficient oxygen to maintain life.

The “if you can talk” notion has persisted even in places like the jail in Montgomery County, Ohio, which had to pay a $3.5 million settlement last year in connection with the 2012 death of an inmate named Robert Richardson, who had been jailed for failing to show up for a child support hearing.

A fellow inmate called for help after Mr. Richardson, 28, had what was described as a possible seizure. Sheriff’s deputies cuffed his hands behind his back and restrained him face down on the floor, pushing on his back and shoulders, and eventually on his head and neck, according to court documents.

Witnesses said Mr. Richardson repeatedly told deputies he could not breathe, until, after 22 minutes, he stopped moving. He was pronounced dead less than an hour later.

It was that jail facility where, six years later, the photocopied sign about being able to breathe if you could talk was posted on the bulletin board.

‘We literally had to sit there and watch my brother die’

Police officers often failed to seek prompt medical attention when a detainee expressed problems breathing, and that has proved to be a factor in several deaths. In some of these cases, the person in custody had recently been Tased or restrained, but other times they were suffering from acute disorders, such as lung infections, and languished for hours. Often, this appeared to be because officers did not take the detainees’ claims seriously.

When 40-year-old Rodney Brown told police officers in Cleveland he could not breathe after being Tased multiple times during a struggle in 2010, one of them responded: “So? Who gives a [expletive]?”

One of the police officers radioed for paramedics but later said he did so only because it was a required procedure when someone had been Tased; he did not convey that Mr. Brown had claimed he could not breathe.

A lawyer for the city in that case told a panel of judges that the officers did not have the medical expertise to know when someone was in a medical crisis or simply exhausted from a vigorous fight, according to an audio recording.

Another troubling case occurred in March 2019 when the police in Montebello, Calif., were called to the home of David Minassian, 39, a former vice president at a property management firm who had suffered a heroin overdose.

His older sister, Maro Minassian, a certified emergency medical technician, had given her brother a dose of naloxone, a medication that reverses the effects of opiate overdoses. He jolted awake but still appeared to have fluid in his lungs, and she dialed 911, anxious to get him to a hospital.

But it was the police, not paramedics, who arrived next. Ms. Minassian said three Montebello officers entered her family’s home as her brother was flailing on the floor.

At least two of the officers slammed him to the ground and put their knees into his back as they tried to cuff him, Ms. Minassian said, and remained on top of him until he stopped talking. “I told them, ‘My brother can’t breathe,’” Ms. Minassian said through tears. “We literally had to sit there and watch my brother die.”

‘Please take the mask off’

Despite years of concerns about some of the potentially dangerous techniques used to subdue people in custody, law enforcement agents have continued to use them.

In the 2018 case involving Ms. Soto’s husband, Marshall Miles, officers struggled to get him into jail after arresting him on suspicion of vandalism and public intoxication.

The Sheriff’s Department had produced training materials as early as 2004 warning about the dangers of suffocation when people were restrained face down or hogtied with their hands and feet linked behind their backs.

But those warnings apparently went unheeded. Mr. Miles, 36, was hogtied while being brought in by the California Highway Patrol, even though the Sheriff’s Department, which runs the jail, no longer allowed the restraint. Deputies removed him from the hogtie but held him face down for more than 15 minutes as he repeatedly said, “I can’t breathe.” They then carried him handcuffed and shackled to a cell, where at least three deputies put their weight on his facedown body while he groaned ever more faintly. About two minutes later, he fell silent and then stopped breathing, according to video of the death.

Sacramento Sheriff Media Bureau

An autopsy concluded that he died from a combination of physical exertion, mixed drug intoxication and restraint by law enforcement. Hogtie restraints were used in four other deaths over the past decade that were examined by The Times.

Another technique used in a series of cases with fatal outcomes, including at least two this year, has been the use of hoods or masks designed to prevent people from spitting on or biting officers. Law enforcement agencies around the world have grappled with whether to use them to protect officers despite concerns about whether the masks are safe.

Video from 2012 shows how one of the masks was used on James W. Brown, an Army sergeant stationed at Fort Bliss in El Paso who had a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sergeant Brown, 26, was supposed to serve a two-day sentence at the county jail for a drunken-driving conviction, but officials said he became aggressive after learning he would be jailed longer.

With his hands cuffed behind him, Sergeant Brown can be seen in a video seated in a chair, surrounded by guards in riot gear holding him down. Deputies had placed a mesh-style mask over the lower half of his face, and he wore it for more than five minutes before telling the guards and a medical worker that he could not breathe.

“Please take the mask off,” Sergeant Brown pleads. “I cannot breathe. Please!”

El Paso Sheriff’s Dept.

He passed out shortly afterward, and he was pronounced dead the next day. A county autopsy ruled that his death was caused by a sickle-cell crisis — natural causes — but a forensic pathologist later hired by the county concluded that his blood condition had been exacerbated by the restraint procedures.

Sergeant Brown’s relatives sued El Paso County, the jail and 10 officers for wrongful death and other claims. The case was later settled.

“I feel like they treated him like he was less than an animal,” said Sergeant Brown’s mother, Dinetta Scott. “Who treats somebody like that?”

Sunday, June 28, 2020

Masks Could Help Stop Coronavirus. So Why Are They Still Controversial? - WSJ

The key secret of Hong Kong’s success, Prof. Yuen said, is that the mask compliance rate during morning rush hour is 97%. The 3% who don’t comply are mainly Americans and Europeans, he said."As countries begin to reopen their economies, face masks, an essential tool for slowing the spread of coronavirus, are struggling to gain acceptance in the West. One culprit: Governments and their scientific advisers.

Researchers and politicians who advocate simple cloth or paper masks as cheap and effective protection against the spread of Covid-19, say the early cacophony in official advice over their use—as well as deeper cultural factors—has hampered masks’ general adoption.

There is widespread scientific and medical consensus that face masks are a key part of the public policy response for tackling the pandemic. While only medical-grade N95 masks can filter tiny viral particles and prevent catching the virus, medical experts say even handmade or cheap surgical masks can block the droplets emitted by speaking, coughing and sneezing, making it harder for an infected wearer to spread the virus.

Although many European countries and U.S. states have made masks mandatory in shops or on public transport, studies show that people are reluctant to wear them unless they have to.

Surveys have found that the willingness to wear masks in these regions has plateaued and in some cases begun to decline, and adoption remains far from universal.

Northern European countries’ residents seem more resistant to wearing them than their Mediterranean neighbors, who have been hit harder by the pandemic. In Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland, fewer than 10% of people said they wear a mask regularly, according to surveys published between February and late May by YouGov PLC.

In the U.S., questions over wearing face masks have fueled heated political debates. The chief health officer in Orange County, Calif., recently resigned after receiving death threats for ordering mask-wearing outside.

Male vanity also appears to be a powerful factor in rejecting masks. A study by Middlesex University London, U.K., and the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute in Berkeley, Calif., found that more men than women agreed that wearing a mask is “shameful, not cool, a sign of weakness, and a stigma.”

In the U.K., with one of the highest Covid-19 death rates globally, only a quarter of respondents to a June 14 YouGov survey said they regularly wear a face mask.

Jez Lloyd, a 56-year-old company director in London, said he would wear a face covering if he were using public transport, but said he doubted their effectiveness, because “they probably let you have a false sense of security.”

A study by the University of Bamberg in Germany published on April 30 found that “acceptance for wearing masks is still low in Europe—many people just feel strange when wearing masks.”

When Covid-19 spread to the West in February, key health-care institutions, such as the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Surgeon General argued against widespread use of face masks outside hospitals. Some experts dismissed simple masks that don’t stop viruses as dangerous, because they could induce a false sense of security in wearers.

U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams tweeted on Feb. 29: “Seriously people—STOP BUYING MASKS!” He has since apologized and now supports wearing them.

White House adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci said this month that he initially dismissed masks because medical workers were facing a shortage in supplies. He, too, is now an advocate.

“Naturally there is a lack of trust in health-care experts now, especially about masks,” said Jeremy Howard, a medical data scientist at the University of San Francisco who runs a pro-mask campaign.

In some countries, such doubts have added to older stigma surrounding other forms of face coverings. In Austria, France and Belgium, Islamic veils are banned. Other European countries have had bans on face masks during public demonstrations. Masks are often prohibited in banks for security reasons.

“I am fully aware that masks are alien to our culture,” said Austria’s Chancellor Sebastian Kurz in April, as he pleaded with citizens to embrace mask-wearing.

Dr. Karl Lauterbach, a German epidemiologist and legislator, said that in a culture of optimizing appearance, rejection of masks is related to identity.

“The acceptance of masks is very low—even as every student of medicine learns that masks prevent infection, which is why we doctors have been wearing them for over 100 years,” Dr. Lauterbach said.

A lack of role models among leaders has made things worse, he added.

Many GOP Lawmakers Back Masks, Tests

Rising Cases Strain Mask Supplies

As States Reopen, Workers, Executive

s Want Government to Make Masks Mandatory

Fauci Warns of Coronavirus Resurgence if States Don’t Adhere to Safety Guidelines (June 16)

Chancellor Angela Merkel, a scientist by training, doesn’t use a mask in public. President Trump has recommended masks but said he won’t wear one.

This reticence is in contrast to Asia, where countries such as South Korea and Taiwan limited the spread of the pandemic early and without instituting severe restrictions like in the West. In Asia, the majority of people voluntarily use face coverings and it is mainly Western expatriates who are reluctant to adopt them, said Prof. Yuen Kwok-Yung, a leading coronavirus expert who advises the Hong Kong government.

Hong Kong, with 7.5 million residents, is one of the most densely populated places on earth, but recorded only six deaths from Covid-19 despite having no lockdown and receiving nearly three million travelers a day from abroad, around half of them from mainland China, where the virus originated.

The key secret of Hong Kong’s success, Prof. Yuen said, is that the mask compliance rate during morning rush hour is 97%. The 3% who don’t comply are mainly Americans and Europeans, he said.

“The only thing you can do is universal masking, that’s what stopped it,” Prof. Yuen said.

Masks as tools of disease prevention go back to the plague doctors of the Middle Ages, while surgical masks were first used in 19th-century Germany. They were improved on and popularized in Asia by Dr. Wu Lien-teh—the first Chinese person to obtain a medical degree from the U.K.’s University of Cambridge—during the Manchurian Plague epidemic of 1910-1911.

Universal masking then became part of the culture in Asia, while Western countries slowly forgot about its benefits, said Dr. Rastislav Madar, an epidemiologist and senior government adviser to the Czech government.

The Czech Republic was the first European country to impose mandatory mask-wearing in some public spaces on March 18, before it recorded the first death by Covid-19. It has since reduced the number of daily new infections to below 50 and has one of the lowest coronavirus death rates in the world.

The country’s public figures, including Prime Minister Andrej Babis, have worn masks in public to encourage their use. Ministers and experts have appeared in online videos explaining their benefits.

One such video inspired Thomas Nitzsche, the mayor of Jena in Germany, to become the first mayor in the country to order mask-wearing in some public spaces—at a time when the federal government was warning against their use.

Jena had one of the region’s fastest infection rates when it imposed the order on April 6. Less than a month later, it was free of Covid-19. This past Monday, the town had one active Covid-19 case.

The masking order was preceded by two weeks of intense campaigning with support from opposition parties helping to overcome the public’s initial resistance, he said.

“The science was clearly in favor of masks, but in the end my decision was driven by common sense.” Mr. Nitzsche said. “This is a respiratory disease, and covering your mouth and nose prevents it from spreading.”

Masks Could Help Stop Coronavirus. So Why Are They Still Controversial? - WSJ

Saturday, June 27, 2020

Obamacare Faces Unprecedented Test as Economy Sinks - The New York Times

The battles over the health law have played out during a decade of continuous economic growth. How it performs as a safety net now may help determine its future.

Frequently Asked Questions and Advice

Updated June 24, 2020What’s the best material for a mask?

Scientists around the country have tried to identify everyday materials that do a good job of filtering microscopic particles. In recent tests, HEPA furnace filters scored high, as did vacuum cleaner bags, fabric similar to flannel pajamas and those of 600-count pillowcases. Other materials tested included layered coffee filters and scarves and bandannas. These scored lower, but still captured a small percentage of particles.

Is it harder to exercise while wearing a mask?

A commentary published this month on the website of the British Journal of Sports Medicine points out that covering your face during exercise “comes with issues of potential breathing restriction and discomfort” and requires “balancing benefits versus possible adverse events.” Masks do alter exercise, says Cedric X. Bryant, the president and chief science officer of the American Council on Exercise, a nonprofit organization that funds exercise research and certifies fitness professionals. “In my personal experience,” he says, “heart rates are higher at the same relative intensity when you wear a mask.” Some people also could experience lightheadedness during familiar workouts while masked, says Len Kravitz, a professor of exercise science at the University of New Mexico.

I’ve heard about a treatment called dexamethasone. Does it work?

The steroid, dexamethasone, is the first treatment shown to reduce mortality in severely ill patients, according to scientists in Britain. The drug appears to reduce inflammation caused by the immune system, protecting the tissues. In the study, dexamethasone reduced deaths of patients on ventilators by one-third, and deaths of patients on oxygen by one-fifth.

What is pandemic paid leave?

The coronavirus emergency relief package gives many American workers paid leave if they need to take time off because of the virus. It gives qualified workers two weeks of paid sick leave if they are ill, quarantined or seeking diagnosis or preventive care for coronavirus, or if they are caring for sick family members. It gives 12 weeks of paid leave to people caring for children whose schools are closed or whose child care provider is unavailable because of the coronavirus. It is the first time the United States has had widespread federally mandated paid leave, and includes people who don’t typically get such benefits, like part-time and gig economy workers. But the measure excludes at least half of private-sector workers, including those at the country’s largest employers, and gives small employers significant leeway to deny leave.

Does asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 happen?

So far, the evidence seems to show it does. A widely cited paper published in April suggests that people are most infectious about two days before the onset of coronavirus symptoms and estimated that 44 percent of new infections were a result of transmission from people who were not yet showing symptoms. Recently, a top expert at the World Health Organization stated that transmission of the coronavirus by people who did not have symptoms was “very rare,” but she later walked back that statement.

What’s the risk of catching coronavirus from a surface?

Touching contaminated objects and then infecting ourselves with the germs is not typically how the virus spreads. But it can happen. A number of studies of flu, rhinovirus, coronavirus and other microbes have shown that respiratory illnesses, including the new coronavirus, can spread by touching contaminated surfaces, particularly in places like day care centers, offices and hospitals. But a long chain of events has to happen for the disease to spread that way. The best way to protect yourself from coronavirus — whether it’s surface transmission or close human contact — is still social distancing, washing your hands, not touching your face and wearing masks.

How does blood type influence coronavirus?

A study by European scientists is the first to document a strong statistical link between genetic variations and Covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus. Having Type A blood was linked to a 50 percent increase in the likelihood that a patient would need to get oxygen or to go on a ventilator, according to the new study.

How many people have lost their jobs due to coronavirus in the U.S.?

The unemployment rate fell to 13.3 percent in May, the Labor Department said on June 5, an unexpected improvement in the nation’s job market as hiring rebounded faster than economists expected. Economists had forecast the unemployment rate to increase to as much as 20 percent, after it hit 14.7 percent in April, which was the highest since the government began keeping official statistics after World War II. But the unemployment rate dipped instead, with employers adding 2.5 million jobs, after more than 20 million jobs were lost in April.

What are the symptoms of coronavirus?

Common symptoms include fever, a dry cough, fatigue and difficulty breathing or shortness of breath. Some of these symptoms overlap with those of the flu, making detection difficult, but runny noses and stuffy sinuses are less common. The C.D.C. has also added chills, muscle pain, sore throat, headache and a new loss of the sense of taste or smell as symptoms to look out for. Most people fall ill five to seven days after exposure, but symptoms may appear in as few as two days or as many as 14 days.

How can I protect myself while flying?

If air travel is unavoidable, there are some steps you can take to protect yourself. Most important: Wash your hands often, and stop touching your face. If possible, choose a window seat. A study from Emory Universityfound that during flu season, the safest place to sit on a plane is by a window, as people sitting in window seats had less contact with potentially sick people. Disinfect hard surfaces. When you get to your seat and your hands are clean, use disinfecting wipes to clean the hard surfaces at your seat like the head and arm rest, the seatbelt buckle, the remote, screen, seat back pocket and the tray table. If the seat is hard and nonporous or leather or pleather, you can wipe that down, too. (Using wipes on upholstered seats could lead to a wet seat and spreading of germs rather than killing them.)

What should I do if I feel sick?

If you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus or think you have, and have a fever or symptoms like a cough or difficulty breathing, call a doctor. They should give you advice on whether you should be tested, how to get tested, and how to seek medical treatment without potentially infecting or exposing others.

Obamacare Faces Unprecedented Test as Economy Sinks - The New York Times