2 Days in May That Shattered Korean Democracy

The US response to a dictatorship’s repression in Gwangju in 1980 was even worse than we thought.

On May 18, South Koreans paused to mark the 40th anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, one of the most traumatic days in their history. The 10-day revoltwas triggered when students and citizens protesting a military coup by a renegade general were attacked by airborne special forces with a viciousness and cruelty that Koreans had not experienced since the darkest days of the Korean War.

The armed resistance by Gwangju’s Citizen Militia liberated the city from the marauding troops. The townspeople, freed from decades of military rule, kept their city running, buried their dead, and transformed themselves into a self-organized system of mutual aid they now call the Gwangju Commune.

Those who died in Gwangju “believed that the survivors would manage to open up a better world” and “were convinced that the defeat of that day would become the victory of tomorrow,” President Moon Jae-in declaredon May 18 in the city square where protesters were killed in 1980.

But their dream of a just society was snuffed out on May 27 by Korean Army troops, who were released from their usual duties on the border with North Korea to reoccupy Gwangju. The official death toll from the uprising stands at 165, but residents believe that more than 300 people were killed, with dozens still unaccounted for.

Despite that defeat, Gwangju’s resistance is now seen as the first shot in the mass movement that, in 1987, swept aside a quarter-century of dictatorship to create one of the world’s most impressive democracies. After years of hostility by conservative governments and attacks on its legitimacy by South Korean rightists, the Gwangju Uprising is widely celebrated in art, music, literature, and film.

President Moon, who came of age as a political activist during South Korea’s authoritarian era, promised to give momentum to an independent truth commissionthat is investigating the Korean military’s use of force, including the question of who ordered the firing on civilians and sent a helicopter to strafe a building near Gwangju’s center. The commission, he said in an interview with the Gwangju affiliate of broadcast company MBC, would also seek to identify individuals who sought to “conceal and distort the truth” of the Gwangju Uprising.

That’s a tall order, because that trail leads straight to the United States and its president, Jimmy Carter, who ran for office in 1976 vowing to make human rights the centerpiece of American foreign policy. Sadly, he failed to do that in Gwangju, sparking the worst crisis in US-Korean relations since 1945. What happened there stoked years of anti-American sentiment, and Gwangju has remained a point of contention ever since.

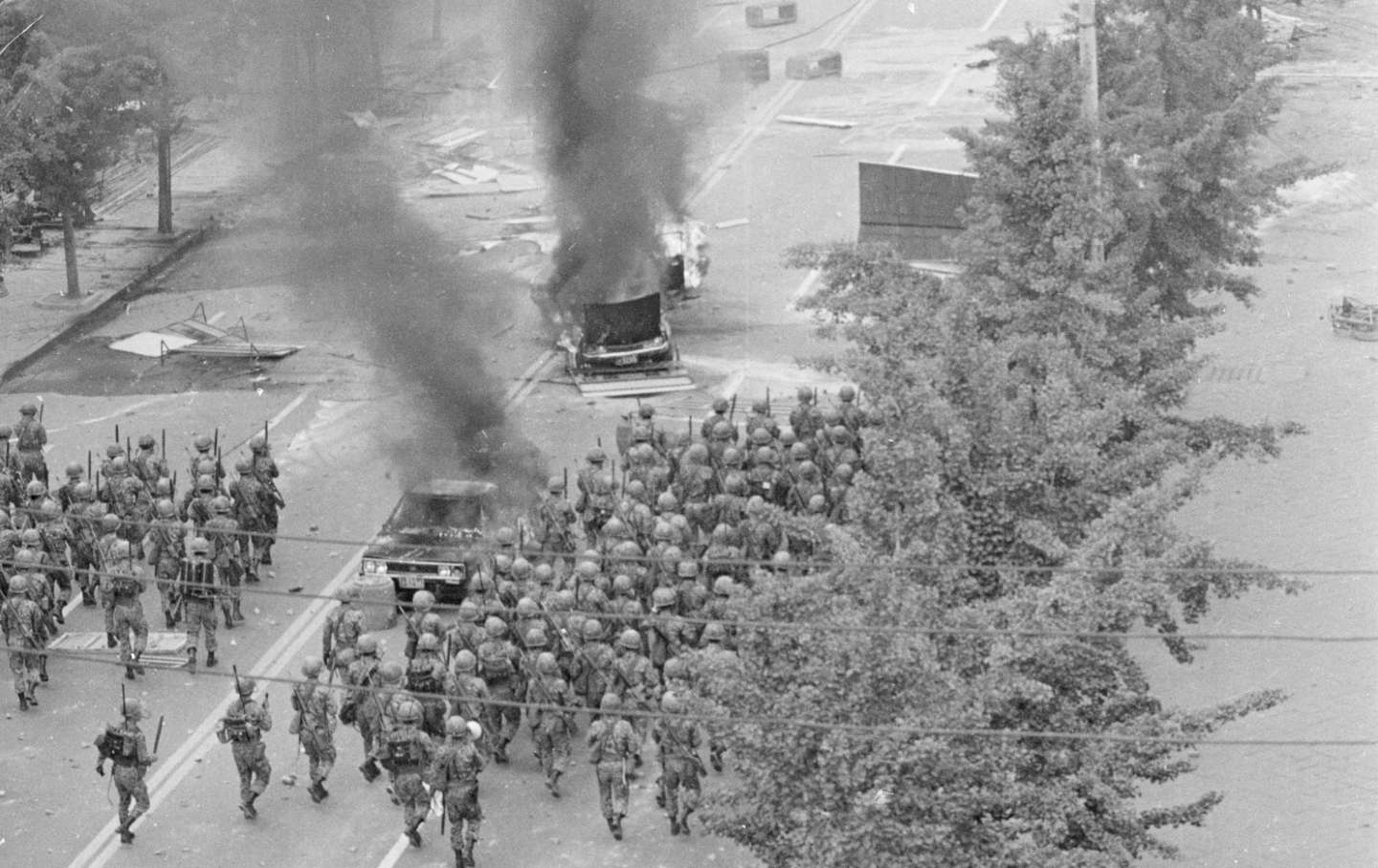

Geumnam-ro, where the airborne troops opened fire on protesters on May 21, 1980. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

As some Koreans are painfully aware, the Carter administration played an essential role in Gwangju by helping the coup leader, Lt. Gen. Chun Doo-hwan, crush the uprising. At a high-level White House meeting on May 22 that we first reported in 1996, Carter’s national security team approved the use of force to retake the city and agreed to provide short-term support to Chun if he agreed to long-term political change (that, of course, didn’t happen until he was forced out by massive protests in 1987).

The stakes were high, and were exacerbated for US policy-makers by the simultaneous crisis over the Islamic revolution in Iran, which eventually brought Carter’s presidency down. As the once-secret minutes to the White House meeting show, plans were also discussed for direct US military intervention in Korea if the situation in Gwangju spiraled out of control.

Within days of the May 22 meeting, the US commander in Korea, Gen. John Wickham, released two divisions of Korean Army troops from the US-South Korean Combined Forces Command (CFC) to retake the city. Fearing that North Korea could intervene, the Pentagon also asked the Korean military to delay its assault on Gwangju to give the US military time to dispatch an aircraft carrier and several spy planes to the peninsula, according to 1989 testimony by South Korea’s martial law commander at the time.

Under that cover, Chun’s forces reentered the city and killed the remaining rebels. Hundreds more were hunted down and tortured in a military prison in Gwangju (it’s now a museum where former prisoners work as guides).

Chun was tried and convicted in 1996 of treason and murder, but he was later pardoned. To this day, he continues to deny any responsibility for the mass killing. In its official statements about the incident, the United States has consistently described Gwangju as a domestic issue for South Korea. “When all the dust settles, Koreans killed Koreans, and the Americans didn’t know what was going on and certainly didn’t approve it,” a State Department official said in 1996 when the White House meeting was first reported.

Carter, who has won global praise for his humanitarian actions since leaving the presidency, has never spoken publicly about his actions in Gwangju (through an intermediary, he declined to comment for this article). His most extensive remarks came in an interview on CNN on June 1, 1980, when he was asked by the journalist Daniel Schorr if US policy in Korea reflected a conflict between human rights and national security.

“There is no incompatibility,” Carter snapped. South Korea, he said, typified a situation where “the maintenance of a nation’s security from Communist subversion or aggression is a prerequisite to the honoring of human rights and the establishment of democratic processes.” Shamefully, none of this was true.

As two of the principal journalists who have investigated US involvement in Gwangju, we know there is much more to the story. Over the past five years, we have interviewed dozens of participants and survivors of the uprising as well as many of the US officials involved in the decision-making that May.

Now, at a time of growing tensions between Seoul and Washington over North Korea and the cost of US military bases in the South, we have uncovered deeper evidence of US complicity in Gwangju and what the US government knew and when it knew it. The story is much worse than we thought.

- When Carter’s White House made the decision to support Chun’s crackdown on the rebellion, it knew that 60 people in Gwangju had been shot to death and over 400 injured just 24 hours earlier, and that Chun was directly responsible. We learned that from notes taken by a senior Pentagon official who was present at the critical White House meeting on May 22.

- General Wickham, the US commander, was fully briefed on the Korean Army’s planning for the May 27 assault on Gwangju in a May 21 meeting with Gen. Lew Byung-hyun, the CFC’s deputy commander. Lew, in turn, told the US general that he was carrying out the wishes of Chun and the coup leaders. Wickham himself confirmed this.

- The US contingency plans for Gwangju included sending additional US ground forces into Korea, a volatile proposal that has never been disclosed before and indicates how seriously US commanders and the Carter administration viewed the situation. If it had escalated, “we would have been much more aggressive” and asked for “additional support from the Pacific Command to suppress the unrest,” General Wickham told us.

- The prime mover in the May 22 meeting was Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, who had been deeply involved over the previous three years restoring once-frayed ties between the US and South Korean militaries and strengthening the Cold War alliance between the US, Korean, and Japanese armed forces.

The Gwangju Uprising was the culmination of a series of events that unfolded in South Korea after the assassination of the former dictator, Park Chung-hee, on October 26, 1979. Fed up with 18 years of harsh dictatorship, Korean students and workers began agitating for a return to democracy. As tensions escalated over the next six months, General Chun and a small group within the military launched a rolling coup, taking over the military, the Korean CIA, and then, on May 17, the government itself.

Protesters and paratroopers clashed for 3 days in Gwangju’s streets. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

“This might have been the longest coup d’état in world history,” says Prof. Kwang Ho Chun, a military strategy specialist and professor of international studies at Jeonbuk National University in North Cholla Province.

In the months before the coup, US officials, led by diplomat (and liberal icon) Richard Holbrooke, tried to find a middle ground between the martial law forces and the pro-democracy movement [see Shorrock, “Debacle in Kwangju,” The Nation, December 9, 1996]. “The United States had at least five months to support Korean democracy,” but failed, Professor Chun said in his interview. While the US emphasis during Gwangju on Korean security was understandable, he said, US officials should have recognized that “sometimes democracy can improve a security situation much faster” than military action.

In fact, as the rebellion intensified, Carter and his advisers began to see it as a much greater threat than Chun’s violent takeover of the government. The situation came to a head over a 48-hour period between May 21, 1980, when Chun’s forces opened fire on the people of Gwangju, and May 22, when the United States threw its support behind the Korean generals.

“May 21, 1 pm, was a very critical point,” Lee Jae-eui, an activist and writer who witnessed the massacre in front of Gwangju’s provincial capitol building, told us as he stood on the exact spot of the firing years later.

For three days, Chun’s paratroopers had used boots, clubs, bayonets, and even flamethrowers to terrorize the city, filling the morgues with the dead and overwhelming the hospitals with bodies ripped apart by the violence. Angered and shocked beyond measure, the people, led at first by young students and joined by taxi drivers, bus drivers, shopkeepers, gangsters, and prostitutes, fought back with vehicles and their own handmade weapons.

By midday, hundreds of thousands of furious Gwangju residents surrounded the paratroopers, who had made their stand at the old capitol building. Suddenly, and without warning, Lee says, the troops opened fire.

Repeated volleys from M-16s turned Gwangju’s now-famous Geumnam-ro Street into a scene of carnage. “I saw so many people killed, so many injured, with blood everywhere,” recalls Lee. “I suddenly had a very strange feeling, that I had to join the struggle to fight the military.” The massacre was indelibly sealed in Korean memory in A Taxi Driver, the acclaimed 2018 film starring Song Kang-ho, the beloved character actor from the Academy Award–winning Parasite.

In the hours that followed, Gwangju residents raided police stations and armories in nearby towns and grabbed carbines and other weapons, and by that evening had taken over the city. But tragically, as recounted in Lee’s famous book about the uprising, Kwangju Diary: Beyond Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age, many of the fighters naively believed that the United States, as the champion of democracy, would come to their aid.

Then came the invasion on May 27. “The citizens of Gwangju felt completely betrayed by the US government and believed that US statements about human rights only extended to the right kind of people and not to them,” says David Dollinger, a former Peace Corps volunteer who was one of the few Americans who remained in the city during the uprising and spent time with the armed rebels in the hours before they were killed.

According to Dollinger, who now lives in London, Gwangju’s hopes for US assistance were raised when people in the city heard reports that a US aircraft carrier had been deployed to Korean waters. But their optimism faded when they learned that troops had been moved from the DMZ and were headed for the city. “By that time, they knew there would be no peaceful ending,” he said. They were right: The Carter administration had already decided their fate in the meeting on May 22.

“At that time, the belief [in Washington] was that 60 were dead and 400 wounded,” said Nicholas Platt, who was a deputy assistant secretary of defense and a senior aide to Defense Secretary Brown. Platt is one of the few people still alive who attended the May 22 White House meeting. During an interview in 2017 at his office at the Asia Society in New York, he pulled out a sheaf of notes he had taken during the meeting and allowed us to film him reading them; their contents are explosive.

At the meeting, Platt recalled, “Gwangju was the main issue.” Yet, judging from his notes and the official minutes, there was no discussion whatsoever about what the people of Gwangju had suffered. Instead, the entire discussion revolved around security. “There was unrest in Gwangju and the Korean military was moving troops in,” said Platt. “We were worried whether they would be able to restore order. There were units that had been moved from the DMZ and we thought that might lessen our ability to deal with the North Koreans.”

Lee, when shown Platt’s notes, was shocked to hear that US officials had such detailed numbers on casualties only 36 hours after the firing on Geumnam-ro. “That number was concealed by the coup leaders,” he said last week, and was not even known to the Korean public until South Korea’s newly elected National Assembly held hearings in 1988.

Hundreds of people in Gwangju were killed by Chun Doo-hwan’s paratroopers. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

We also interviewed General Wickham about his meetings with General Lew, his deputy commander at the CFC (then, as now, the US commander of the CFC controls all US and Korean troops during times of war). Significantly, they met on the afternoon of May 21, within hours of the mass shooting in Gwangju.

“Lew and I met several times a day on Gwangju,” Wickham said in an interview at his home in Texas in 2017. The gist of his conversations, he said, were then relayed via “secure phone” to the other members of the US country team in Seoul, Ambassador William Gleysteen and CIA station chief Robert Brewster.

“General Lew was worried about Gwangju morphing into warfare around the country, and he wanted to tamp it down the best he could. That’s why he and I talked about how to do that with minimal force [and] what’s the best way to do it” said Wickham. But, in carrying out the operation, Lew and other Korean commanders understood they were doing the bidding of General Chun and the officers who had seized control of the army in December.

“The coup leaders were saying we have to suppress this, it’s a threat to our coup,” Wickham recalled of his conversation with General Lew (in 1981, after Chun became president, Lew was named South Korea’s ambassador to the United States, maintaining his role as a key liaison with Washington). Brewster and Gleysteen sent the information from Wickham’s meeting to Washington in top secret cables (which we later obtained) in preparation for the White House meeting the next day.

In a critical but highly redacted report, the CIA declared that “the insurrection in Kwangju…poses a serious challenge to the Martial Law Command’s authority.… Violence has spread to about 16 towns within a 50-mile radius of Kwangju, all in South Cholla Province.”

While “trying to negotiate a cease-fire,” the military “probably will have to use force to end the rebellion,” the agency concluded, adding that Korean generals “would be hard pressed to deal with simultaneous uprisings of the same magnitude in other areas.” These words were repeated almost verbatim by Gleysteen in his cables, who added this observation about Chun and his martial law group: “The December 12 generals obviously feel threatened by the whole affair.”

Given the overwhelming focus on a military response, it’s no surprise that, as Platt’s notes reveal, Defense Secretary Brown was the dominant figure in these deliberations. This was a natural progression from his role as the chief US interlocutor with the Korean military before and after Park’s 1979 assassination.

Brown and the Joint Chiefs were in constant contact with the Korean military leadership, even after General Chun seized control of the army in his December 12 coup. As shown in Platt’s notes, Brown’s forceful views overrode others who were deeply concerned about Chun, such as Warren Christopher, then the deputy secretary of state.

“Chun has done real harm and set the process back,” Christopher said at one point in the meeting. His boss, Secretary of State Edmund Muskie, agreed, saying that Chun “could become a liability,” and asking, “Aren’t we going to be hostage to them?” When David Aaron, an aide to National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, raised the possibility of urging Chun to step down, Brown intervened. “If he goes that will create a vacuum.” Brown said, according to Platt’s notes.

Worse, the defense secretary even seemed to admire Chun and his martial law group. “They have been quite good about using force,” he said. With Chun clearly in control, said Platt, Brown’s Pentagon even established “a special channel” between the general and the Joint Chiefs of Staff through Gen. John Vessey, the deputy chief of staff of the US Army who had been the US commander in Korea prior to Wickham and knew Chun well.

For Koreans, one of the most enraging aspects of this meeting was Brown’s statement, as recorded by Platt, that Koreans would accept the administration’s support for Chun because “Koreans go with who’s winning.” Months later, General Wickham would amplify this thought in public, saying that Koreans were “lemmings” who would follow any strong leader.

Such comments reflect the predominant thinking among US leaders at the time that Koreans were simply not ready for democracy and would easily accept another military strongman, even after 18 years of dictatorship. Brown, who died in 2019, did not respond when we contacted him in 2017.

Brown’s official biography portrays him as a valiant fighter for Korean democracy, emphasizing his forceful meeting with President Chun in December 1980 to persuade him not to execute Kim Dae-jung, the dissident leader who would later be elected president. As for the White House meeting about Gwangju on May 22, 1980, the bio blandly notes that participants “decided that the ROK had to resume authority in Kwangju” before the United States could resume its pressure for liberalization. That’s an interesting euphemism for helping to put down an insurrection against brutality.

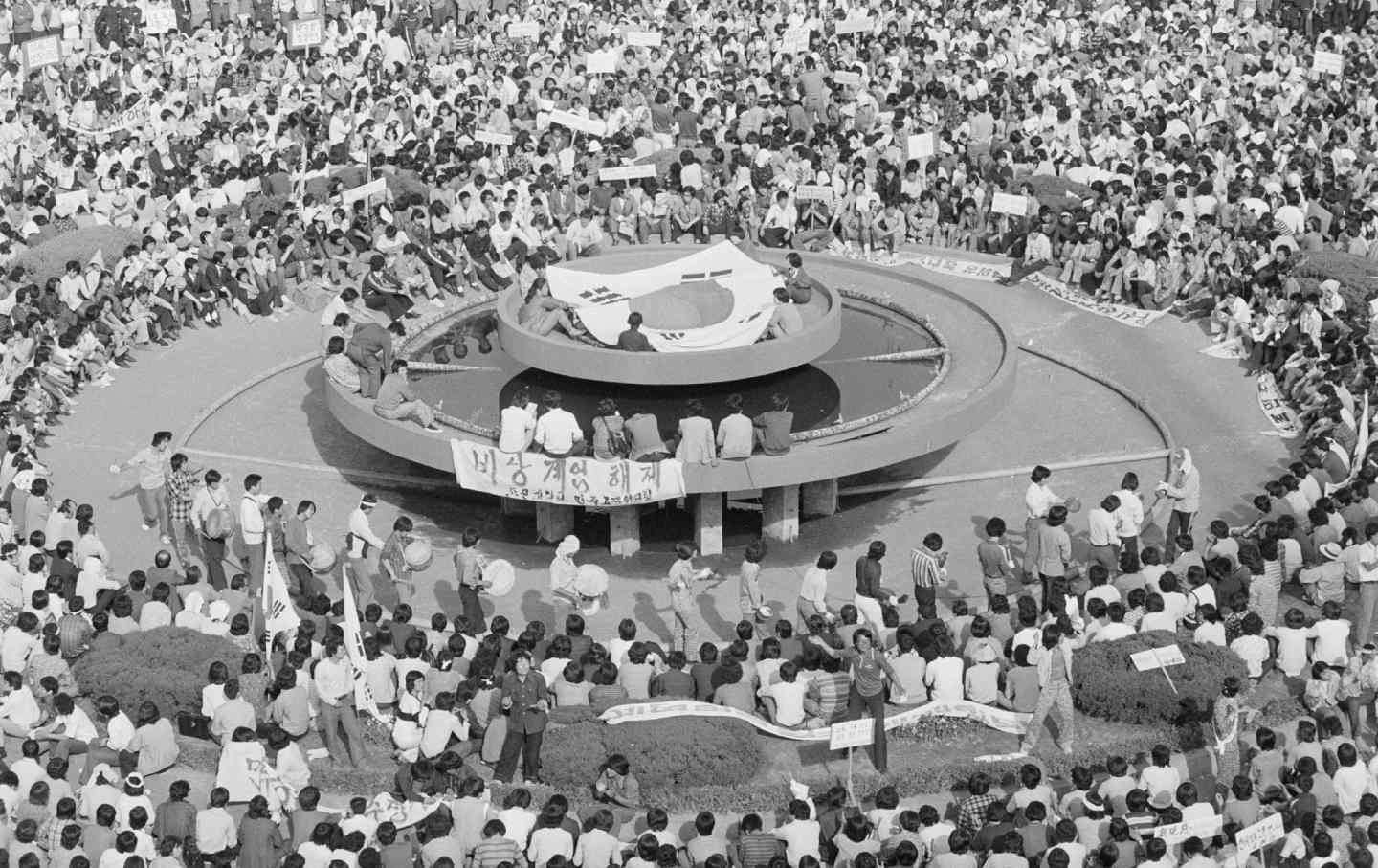

This traffic circle was the center of the uprising. Today it is known as Democracy Plaza. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

This May 11, as this article was being prepared, the State Department, acting “in the spirit of friendship and cooperation between allies,” released several dozen newly declassified documents related to Gwangju to the Moon government in Seoul. Many were first released in redacted form 24 years ago, and most are fairly innocuous, apparently designed to put US policy in the best light possible. But one of the cables illustrates the kind of disinformation that the Carter administration relied on to make its decisions about Gwangju.

On May 18, 1980, Gen. Lee Hui-sung, the martial law commander, toldAmbassador Gleysteen that if the uprising in Gwangju was not contained, South Korea ”would be communized in a manner similar to Vietnam.” Given what had inspired the uprising, this statement was ludicrous, but it was apparently enough to convince Carter and his advisers that they were on the right course. A spokesperson for Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, asked to comment on Carter’s policy at the time, said she had “nothing to add” to previous US policy statements.

Ironically, the CIA may have had the best understanding in the US government about Chun. In 1987, as anger was building in Seoul over Chun’s repressive rule, the agency informed the Reagan administration that Chun’s crackdown in Gwangju had led many Koreans to believe that his military was a greater threat to their security than North Korea.

“A tarnishing of the military’s image—the result of its close association with the highly unpopular rule of [Chun] and the Army’s brutal suppression of riots in Kwangju in 1980—has convinced many officers that South Koreans have grown antagonistic toward them and complacent about the North Korea threat,” the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence wrote in a secret assessment of the Korean military.

But only after the protests in the summer of 1987 threatened to create another Gwangju did Chun agree to step down and allow direct presidential elections for the first time. Out of that struggle, and inspired by the Gwangju democratic movement of 1980, South Korea’s democracy was born.

The Korean people did it again with the Candlelight Revolution of 2016–17, which led to the impeachment of another unpopular president, Park Geun-hye (the daughter of former dictator Park Chung-hee) and the subsequent election, in May 2017, of Moon Jae-in. The real “winners” of Korean history, in other words, were the citizens of Gwangju. But, sadly, they and many other Koreans had to suffer under military dictatorship for seven more years after their uprising.

Should the United States apologize for what happened in Gwangju in 1980? The Nation put that question to President Moon in an interview in Gwangju three days before his election. Moon, characteristically, rejected the notion. “It doesn’t matter, because we have moved on, and established democracy for ourselves,” he said. An official in Moon’s Blue House, citing the “government to government” discussions going on about the investigation into May 18, would not comment.

But given what we know now about US actions during Gwangju, the time has come for a formal apology, those who survived the uprising say. “They have to give a sincere apology,” says author Lee, who is famous in Gwangju for his continued activism on the issue. David Dollinger, the former Peace Corps volunteer, is adamant on the question.

“When I think about Gwangju, I am brought to tears and am truly embarrassed by my government from that time,” he says. That feeling, in part, reflects his anger over being forced to resign from the Peace Corps after he went public with his critique at the time of the uprising. An apology, he says, “should be done not through documents but by an official of the US government kneeling to the mothers and citizens of Gwangju asking for forgiveness. It should then apologize to all the people of Korea, for not listening to its citizens.”

No comments:

Post a Comment