I publish an "Editorial and Opinion Blog", Editorial and Opinion. My News Blog is @ News . I have a Jazz Blog @ Jazz and a Technology Blog @ Technology. My domain is Armwood.Com @ Armwood.Com.

What To Do When You're Stopped By Police - The ACLU & Elon James White

Know Anyone Who Thinks Racial Profiling Is Exaggerated? Watch This, And Tell Me When Your Jaw Drops.

This video clearly demonstrates how racist America is as a country and how far we have to go to become a country that is civilized and actually values equal justice. We must not rest until this goal is achieved. I do not want my great grandchildren to live in a country like we have today. I wish for them to live in a country where differences of race and culture are not ignored but valued as a part of what makes America great.

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Opinion | Coronavirus, Racism and Injustice: No One Is Coming to Save Us - The New York Times

"Eventually doctors will find a coronavirus vaccine, but black people will continue to wait for a cure for racism.

Contributing Opinion Writer.

After Donald Trump maligned the developing world in 2018, with the dismissive phrase “shithole countries,” I wrote that no one was coming to save us from the president. Now, in the midst of a pandemic, we see exactly what that means.

The economy is shattered. Unemployment continues to climb, steeply. There is no coherent federal leadership. The president mocks any attempts at modeling precautionary behaviors that might save American lives. More than 100,000 Americans have died from Covid-19.

Many of us have been in some form of self-isolation for more than two months. The less fortunate continue to risk their lives because they cannot afford to shelter from the virus. People who were already living on the margins are dealing with financial stresses that the government’s $1,200 “stimulus” payment cannot begin to relieve. A housing crisis is imminent. Many parts of the country are reopening prematurely. Protesters have stormed state capitals, demanding that businesses reopen. The country is starkly dividing between those who believe in science and those who don’t.

Quickly produced commercials assure us that we are all in this together. Carefully curated images, scored by treacly music, say nothing of substance. Companies spend a fortune on airtime to assure consumers that they care, while they refuse to pay their employees a living wage.

Commercials celebrate essential workers and medical professionals. Commercials show how corporations have adapted to “the way we live now,” with curbside pickup and drive-through service and contact-free delivery. We can spend our way to normalcy, and capitalism will hold us close, these ads would have us believe.

Some people are trying to provide the salvation the government will not. There are community-led initiatives for everything from grocery deliveries for the elderly and immunocompromised to sewing face masks for essential workers. There are online pleas for fund-raising. Buy from your independent bookstore. Get takeout or delivery from your favorite restaurant. Keep your favorite bookstore open. Buy gift cards. Pay the people who work for you, even if they can’t come to work. Do as much as you can, and then do more.

These are all lovely ideas and they demonstrate good intentions, but we can only do so much. The disparities that normally fracture our culture are becoming even more pronounced as we decide, collectively, what we choose to save — what deserves to be saved.

And even during a pandemic, racism is as pernicious as ever. Covid-19 is disproportionately affecting the black community, but we can hardly take the time to sit with that horror as we are reminded, every single day, that there is no context in which black lives matter.

Breonna Taylor was killed in her Louisville, Ky., home by police officers looking for a man who did not even live in her building. She was 26 years old. When demonstrations erupted, seven people were shot by police.

Ahmaud Arbery was jogging in South Georgia when he was chased down by two armed white men who suspected him of robbery and claimed they were trying perform a citizen’s arrest. One shot and killed Mr. Arbery while a third person videotaped the encounter. No charges were filed until the video was leaked and public outrage demanded action. Mr. Arbery was 25 years old.

In Minneapolis, George Floyd was held to the ground by a police officer kneeling on his neck during an arrest. He begged for the officer to stop torturing him. Like Eric Garner, he said he couldn’t breathe. Three other police officers watched and did not intervene. Mr. Floyd was 46 years old.

These black lives mattered. These black people were loved. Their losses to their friends, family, and communities, are incalculable.

Demonstrators in Minneapolis took to the street for several days, to protest the killing of Mr. Floyd. Mr. Trump — who in 2017 told police officers to be rough on people during arrests, imploring them to “please, don’t be too nice” — wrote in a tweet, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.” The official White House Twitter feed reposted the president’s comments. There is no rock bottom.

Christian Cooper, an avid birder, was in Central Park’s Ramble when he asked a white woman, Amy Cooper, to comply with the law and leash her dog. He began filming, which only enraged Ms. Cooper further. She pulled out her phone and said she was going to call the police to tell them an African-American man was threatening her.

She called the police. She knew what she was doing. She weaponized her whiteness and fragility like so many white women before her. She began to sound more and more hysterical, even though she had to have known she was potentially sentencing a black man to death for expecting her to follow rules she did not think applied to her. It is a stroke of luck that Mr. Cooper did not become another unbearable statistic.

An unfortunate percentage of my cultural criticism over the past 11 or 12 years has focused on the senseless loss of black life. Mike Brown. Trayvon Martin. Sandra Bland. Philando Castile. Tamir Rice. Jordan Davis. Atatiana Jefferson. The Charleston Nine.

These names are the worst kind of refrain, an inescapable burden. These names are hashtags, elegies, battle cries. Still nothing changes. Racism is litigated over and over again when another video depicting another atrocity comes to light. Black people share the truth of their lives, and white people treat those truths as intellectual exercises.

They put energy into being outraged about the name “Karen,” as shorthand for entitled white women rather than doing the difficult, self-reflective work of examining their own prejudices. They speculate about what murdered black people might have done that we don’t know about to beget their fates, as if alleged crimes are punishable by death without a trial by jury. They demand perfection as the price for black existence while harboring no such standards for anyone else.

Some white people act as if there are two sides to racism, as if racists are people we need to reason with. They fret over the destruction of property and want everyone to just get along. They struggle to understand why black people are rioting but offer no alternatives about what a people should do about a lifetime of rage, disempowerment and injustice.

When I warned in 2018 that no one was coming to save us, I wrote that I was tired of comfortable lies. I’m even more exhausted now. Like many black people, I am furious and fed up, but that doesn’t matter at all.

I write similar things about different black lives lost over and over and over. I tell myself I am done with this subject. Then something so horrific happens that I know I must say something, even though I know that the people who truly need to be moved are immovable. They don’t care about black lives. They don’t care about anyone’s lives. They won’t even wear masks to mitigate a virus for which there is no cure.

Eventually, doctors will find a coronavirus vaccine, but black people will continue to wait, despite the futility of hope, for a cure for racism. We will live with the knowledge that a hashtag is not a vaccine for white supremacy. We live with the knowledge that, still, no one is coming to save us. The rest of the world yearns to get back to normal. For black people, normal is the very thing from which we yearn to be free.".

Opinion | Coronavirus, Racism and Injustice: No One Is Coming to Save Us - The New York Times

Saturday, May 30, 2020

George Floyd Updates: ‘Absolute Chaos’ in Minneapolis as Protests Grow Across U.S. - The New York Times

"Minnesota’s governor said the police and National Guard had been overwhelmed by protests, which raged even after a former police officer was charged with murdering George Floyd.

Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota vowed that more National Guard troops would be deployed, and did not rule out the possibility of bringing in the U.S. military.

Demonstrations raged overnight across the U.S. in the third night of unrest in response to George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis police custody.CreditCredit...Victor J. Blue for The New York Times

Fires, gunshots and arrests mark another night of destruction in Minneapolis.

Minnesota’s top officials acknowledged early Saturday morning that they had underestimated the destruction that protesters in Minneapolis were capable of inflicting as a newly issued curfew did little to stop people from burning buildings and turning the city’s streets into a smoky battleground.

Gov. Tim Walz said at a news conference that the police and National Guard soldiers had been overwhelmed by protesters set on causing destruction days after George Floyd was pinned to the ground by an officer before dying.

“Quite candidly, right now, we do not have the numbers,” Mr. Walz said. “We cannot arrest people when we’re trying to hold ground because of the sheer size, the dynamics and the wanton violence that’s coming out there.”

State officials said that a series of errors and misjudgments — including the Minneapolis police abandoning a precinct on Thursday that protesters overtook and burned — had allowed demonstrators to create what Mr. Walz called “absolute chaos.”

Politicians and the police had not expected the protests to grow for a fourth night on Friday, after a police officer was charged with third-degree murder and a curfew went into effect at 8 p.m. But grow they did, and law enforcement officers struggled to hold their ground, with National Guard troops retreating from angry protesters at one point.

Gunshots rang out near a different police precinct and flames streamed from businesses over several city blocks — a gas station, a post office, a bank, a restaurant — as residents asked where the police and firefighters had gone.

“There’s simply more of them than us” Mr. Walz said of the protesters.

The governor vowed that more Guard troops would be deployed and that the authorities would not let the destruction continue. Even so, state officials did not show much optimism that the demonstrations would stop, and Mr. Walz did not rule out the possibility of bringing in the U.S. military.

Commissioner John Harrington of the state’s Department of Public Safety said the police were preparing to be at the center of an “international event” on Saturday, pledging to "restore order” on the same Minneapolis block that was burning as he spoke. Mr. Harrington said he expected the largest crowds the state had ever seen.

Dozens of other cities grappled with protests on their streets that seemed to largely overwhelm the authorities. Residents burned police cars in Atlanta, charged a police precinct in New York and set fires in downtown San Jose, Calif. In some cities, including Los Angeles and Portland, Ore., some people smashed the windows of stores and stole things from display cases.

In Minneapolis, protesters gathered near the Police Department’s Fifth Precinct the day after they had taken over the Third Precinct and set it on fire. Unlike Thursday, the police did not flee, and arrested several protesters who they said refused to disperse.

Paul E. Gazelka, the Republican majority leader of the State Senate, told the KARE 11 news channel that he was frustrated the police had not acted more swiftly to clear the streets.

“You cannot allow anarchy,” he said. “You cannot allow this lawlessness to continue.”

The protests on Friday had largely been peaceful until nightfall, when people began setting fire to vehicles and buildings and launching fireworks toward the police, who in recent days have fired projectiles and used pepper spray to keep people at bay.

Mayor Jacob Frey of Minneapolis, looking weary after four days of outrage in his city, pleaded with residents to go home and stop burning down the local businesses that he said were even more vital in the middle of a pandemic.

“You’re not getting back at the police officer that tragically killed George Floyd by looting a town,” Mr. Frey said. “You’re not getting back at anybody.”

A protester after being tear gassed by the police in Louisville on Friday.Credit...Whitney Curtis for The New York Times

Protesters across the country blocked highways and clashed with the police.

Chanting “Hands up! Don’t shoot” and “I can’t breathe,” thousands of protesters gathered in cities across the country on Friday night after a fired Minneapolis police officer was charged with third-degree murder in the death of George Floyd.

Unrest following Mr. Floyd’s death in custody gave way to a fourth night of demonstrations. Crowds shut down Los Angeles freeways, clashed with the police in Dallas and defaced the CNN Center in Atlanta, where Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms declared, “This is not how we change America.”

Demonstrators in many other cities, including New York, also gathered to voice their anger:

A large crowd in Washington chanted outside the White House, prompting the Secret Service to temporarily lock down the building. Video on social media showed demonstrators knocking down barricades and spray-painting other buildings.

A march in Houston, where Mr. Floyd grew up, briefly turned chaotic as the windows of a police S.U.V. were smashed and at least 12 protesters were arrested. As a standoff continued, the police shut all roads into and out of downtown. “We don’t want these young people’s legitimate grievances and legitimate concerns to be overshadowed by a handful of provocateurs and anarchists,” the city’s police chief, Art Acevedo, said in an interview.

Images from news helicopters above San Jose, Calif., showed protesters throwing objects at police officers, blocking a major freeway and setting fires downtown. Mayor Sam Liccardo said in an interview that he watched from City Hall as a peaceful protest — what he called people “expressing their righteous outrage on the injustice in Minneapolis” — turned violent.

Demonstrators in Los Angeles blocked the 110 Freeway, marching through downtown and around Staples Center. Local television footage showed police officers clashing with a crowd suspected of vandalizing a patrol car. By 9:30 p.m., L.A.P.D. had declared all of downtown to be an unlawful assembly and was warning residents of the loft districts to stay inside.

The police said a 19-year-old man was killed in Detroit after someone opened fire into a crowd of demonstrators late Friday. Earlier, a small group gathered outside Police Headquarters, declaring “Black is not a crime.” The demonstration swelled to more than 1,000 protesters, who blocked traffic while marching on major thoroughfares.

In downtown Dallas, protesters and the police clashed during a demonstration blocks from City Hall. Protesters blocked the path of a police vehicle and then started banging on its hood. Officers eventually responded with tear gas, and a flash-bang was later heard.

In Portland, Ore., demonstrators broke into the Multnomah County Justice Center and lit a fire inside the building late Friday night, authorities said.

Hundreds of protesters converged on Civic Center Park in Denver, waving signs and chanting as Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” played over a loudspeaker. Some thrust fists in the air and scrawled messages on the ground in chalk, according to a news broadcast.

Protesters in Milwaukee briefly shut down part of a major highway, according to WTMJ-TV, and demonstrators shouted “I can’t breathe” — echoing Mr. Floyd’s anguished plea and the words of Eric Garner, a black man who died in New York police custody in 2014.

Fired officer is charged with third-degree murder after George Floyd’s death.

The former Minneapolis police officer who was seen on video using his knee to pin down George Floyd, who died shortly after, was arrested and charged with murder, the authorities announced on Friday.

The former officer, Derek Chauvin, 44, was charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter, Mike Freeman, the Hennepin County attorney, said. An investigation into the other three officers who were present at the scene on Monday was continuing, he said.

Mr. Floyd’s relatives said in a statement that they were disappointed by the decision not to seek first-degree murder charges. Mr. Floyd, 46, died on Monday after pleading “I can’t breathe” while Mr. Chauvin pressed his knee into Mr. Floyd’s neck, in an encounter that was captured on video.

Third-degree murder does not require an intent to kill, according to the Minnesota statute, only that the perpetrator caused someone’s death in a dangerous act “without regard for human life.” Charges of first- and second-degree murder require prosecutors to prove, in almost all cases, that the perpetrator made a decision to kill the victim.

Mr. Chauvin was also charged with second-degree manslaughter, a charge that requires prosecutors to prove he was so negligent as to create an “unreasonable risk,” and consciously took the chance that his actions would cause Mr. Floyd to be severely harmed or die.

Camille J. Gage, 63, an artist and musician who joined the protests, said she was relieved that Mr. Chauvin had been charged. “How can anyone watch that video and think it was anything less?” she said. “Such blatant disregard for another living soul.”

Video

Derek Chauvin, the former police officer who was seen on video using his knee to pin down George Floyd, was charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter.

The developments came after a night of chaos in which protesters set fire to a police station in Minneapolis, the National Guard was deployed to help restore order, and President Trump injected himself into the mix with tweets that appeared to threaten violence against protesters.

Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota, a Democrat, expressed solidarity with the protesters during a news conference on Friday, but said that a return to order was needed to lift up the voices of “those who are expressing rage and anger and those who are demanding justice” and “not those who throw firebombs.”

A lawyer for Mr. Chauvin’s wife, Kellie, said that she was devastated by Mr. Floyd’s death and expressed sympathy for his family and those grieving his loss. The case has also led Ms. Chauvin to seek a divorce, the lawyer, Amanda Mason-Sekula, said in an interview on Friday night.

President Trump, who previously called the video of Mr. Floyd’s death “shocking,” drew criticism for a tweet early Friday that called the protesters “thugs” and said that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” The comments prompted Twitter to attach a warning to the tweet, saying that it violated the company’s rules about “glorifying violence.”

The president gave his first extensive remarks on the protests later on Friday at the White House, declaring that “we can’t allow a situation like happened in Minneapolis to descend further into lawless anarchy and chaos. It’s very important, I believe, to the family, to everybody, that the memory of George Floyd be a perfect memory.”

Addressing his earlier Twitter comments, Mr. Trump said, “The looters should not be allowed to drown out the voices of so many peaceful protesters. They hurt so badly what is happening.”

A demonstration turned destructive in Atlanta on Friday night, as hundreds of protesters took to the streets, smashing windows and clashing with the police.

They gathered around Centennial Olympic Park, the city’s iconic tourist destination. People jumped on police cars. Some climbed atop a large red CNN sign outside the media company’s headquarters and spray-painted messages on it. Others threw rocks at the glass doors of the Omni Hotel and shattered windows at the College Football Hall of Fame, where people rushed in and emerged with branded fan gear.

Jay Clay, 19, an Atlanta resident and graphic designer, watched the protests from across a street with a mixture of curiosity and solidarity.

“After all this injustice and prejudice, people get fed up,” Mr. Clay said. “I wanted to come down and check it out. But this feels like it’s getting out of hand.”

Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms pleaded for calm as the demonstrations unfolded.

“It’s enough. You need to go home,” she said. “We are all angry. This hurts. This hurts everybody in this room. But what are you changing by tearing up a city? You’ve lost all credibility now. This is not how we change America. This is not how we change the world.”

Bernice King, the youngest daughter of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., also spoke at the news conference, invoking her father’s legacy.

“Violence in fact creates more problems. It is not a solution,” Ms. King said. She said she felt and understood the anger of protesters but added, “There are people who would try to incite a race war in this country. Let’s not fall into their hands and into their trap. There’s another way.”

As the protests went on, police officers in riot gear were gathering. By 9:30 p.m., tear gas canisters were launched, and a wave of protesters ran back toward the park.

Tensions flared in New York for the second night in a row as thousands of protesters stormed the perimeter of Barclays Center in Brooklyn, trading projectiles of plastic water bottles, debris and tear gas and mace with police officers.

The protest had begun peacefully Friday afternoon, with hundreds chanting “Black lives matter” and “We want justice” in downtown Manhattan. But the demonstrations took a turn in Brooklyn, where officers made between 50 and 100 arrests, a senior police official said.

Officers with twist-tie handcuffs hanging from their belts stood next to Department of Corrections buses and squad cars with lights flashing, encircling the perimeter. A police helicopter and a large drone whirred in the hot air overhead.

Protesters were later seen throwing water bottles, an umbrella and other objects at officers, who responded by shooting tear gas into the crowd.

As that crowd scattered, protesters gathered in the streets in the nearby Fort Greene neighborhood, continuing to chant at the police. An empty patrol van was set ablaze, then pillaged, as people pried the doors off the hinges. Fireworks were thrown into the burned shell of the vehicle. Scribbled on the hood was the phrase “dead cops.”

By 10 p.m., riot police had descended on the neighborhood. Another police official had described the scene in parts of the borough as “out of control.”

Earlier in the evening, several hundred people filled Foley Square near the city’s criminal courthouses. After a man in a green sweatshirt crossed a police barricade, he was swarmed by officers while protesters screamed. He was led away on foot in handcuffs.

“It was kind of his mistake,” said Jason Phillips, 27, of Queens. “But they were trying to push him back, and as they pushed him back, he slipped, and they took that as some type of threat.”

Despite the frustrations of demonstrators on Friday, the police said the number of people detained was much smaller than the night before, when 72 people were arrested.

In a probable cause affidavit released on Friday after the charges against Mr. Chauvin were filed, prosecutors said that the former officer held his knee to Mr. Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes. “Two minutes and 53 seconds of this was after Mr. Floyd was non-responsive,” the affidavit said.

But preliminary results from an autopsy indicated that Mr. Floyd did not die from suffocation or strangulation, prosecutors wrote, and that “the combined effects” of an underlying heart condition, any potential intoxicants and the police restraint likely contributed to his death. He also began complaining that he could not breathe before he was pinned down, the affidavit said.

The officers’ body cameras were running throughout the encounter, prosecutors said.

Four officers responded to a report at about 8 p.m. on Monday about a man suspected of making a purchase from a store with a fake $20 bill, prosecutors said. After learning that the man was parked near the store, the first two responding officers, who did not include Mr. Chauvin, approached Mr. Floyd, a former high school sports star who worked as a bouncer at a restaurant in Minneapolis.

Mr. Floyd, who was in a car with two other people, was ordered out and arrested. But when the officers began to move him toward a squad car, he stiffened and resisted, according to the affidavit. While still standing, Mr. Floyd began to say he could not breathe, the affidavit said.

7 pages, 0.69 MB

That was when Mr. Chauvin, who was among two other officers who arrived at the scene, got involved, prosecutors said. Around 8:19 p.m., Mr. Chauvin pulled Mr. Floyd out of the squad car and placed his knee onto Mr. Floyd’s neck area, holding him down on the ground while another officer held his legs. At times, Mr. Floyd pleaded, the affidavit said, saying, “I can’t breathe,” “please” and “mama.”

“You are talking fine,” the officers said, according to the affidavit, as Mr. Floyd wrestled on the ground.

At 8:24 p.m., Mr. Floyd went still, prosecutors said. A minute later, one of the other officers checked his wrist for a pulse but could not find one. Mr. Chauvin continued to hold his knee down on Mr. Floyd’s neck until 8:27, according to the affidavit.

The other officers, who have been identified as Thomas Lane, Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng, are under investigation. Mr. Freeman, the county attorney, said he expected to bring more charges in the case but offered no further details.

Richard Frase, a professor of criminal law at the University of Minnesota, said it was reasonable for prosecutors to charge Mr. Chauvin with third-degree murder, as opposed to a more severe form of murder, which would require proving that Mr. Chauvin intended to kill Mr. Floyd.

Professor Frase said the case against Mr. Chauvin appeared to be even stronger than the one that Hennepin County prosecutors brought against Mohamed Noor, a former Minneapolis police officer who shot and killed Justine Ruszczyk in 2017.

Mr. Noor was charged with the same combination of crimes, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter, and was convicted of both.

In that case, Professor Frase said, the officer had seemingly panicked and fired a single shot. “There’s a question of whether he even had time to be reckless,” he said, referring to Mr. Noor. “Here, there’s eight minutes.”

The criminal complaint against Mr. Chauvin, Professor Frase said, did not identify any specific motive for officers to kill Mr. Floyd, which he said essentially ruled out first or second-degree murder unless additional evidence surfaced.

Ben Crump, a civil rights lawyer representing Mr. Floyd’s family, released a statement on Friday calling the arrest of Mr. Chauvin “a welcome but overdue step on the road to justice.” But he said the charges did not go far enough.

“We expected a first-degree murder charge. We want a first-degree murder charge. And we want to see the other officers arrested,” said the statement, which was attributed to Mr. Floyd’s family and to Mr. Crump.

“The pain that the black community feels over this murder and what it reflects about the treatment of black people in America is raw and is spilling out onto streets across America,” the statement said.

Professor Frase said he expected Mr. Chauvin’s lawyers to seize on the preliminary autopsy findings that showed that Mr. Floyd had not died of asphyxiation, which could form the basis for an argument that there was no way Mr. Chauvin could have expected him to die. But Professor Frase said another common strategy used by police officers facing charges of brutality — arguing that they were in harm’s way — may be unlikely to convince a jury.

“In this case, there was nobody but Mr. Floyd in danger,” he said. “And there was all that time when it seems there was no need to keep kneeling on his neck like that.”

George Floyd Updates: ‘Absolute Chaos’ in Minneapolis as Protests Grow Across U.S. - The New York Times

Friday, May 29, 2020

Opinion | George Floyd, Police Accountability and the Supreme Court - The New York Times

/https%3A%2F%2Fstatic01.nyt.com%2Fimages%2F2020%2F05%2F30%2Fopinion%2F30policeprint1%2Fmerlin_172907484_2f7cb8ad-dc3c-428b-910b-8e691bf0326b-articleLarge.jpg%3Fquality%3D75%26auto%3Dwebp%26disable%3Dupscale)

"The courts protected police abuses for years before George Floyd’s death. It’s time to rethink “qualified immunity.”

The editorial board is a group of opinion journalists whose views are informed by expertise, research, debate and certain longstanding values. It is separate from the newsroom.

A Minneapolis police officer, who was filmed kneeling on George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes until the life left his body, has been fired, arrested and charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter. That is a step toward justice. Those who take a life should face a jury of their peers. But the rarity of the arrest, the fact that police officers who brutalize or even kill other people while wearing a badge so seldom end up facing any consequences is an ugly reminder of how unjust America’s legal system can be.

There is a common refrain from street protesters in the wake of death after death after death after death of men of color at the hands of the police: “No justice, no peace.” In the absence of justice, there has been no peace.

Demonstrations in nearly a dozen cities, some of which turned violent, erupted in response to the killing of Mr. Floyd. At least seven people were shot in Louisville. Windows were broken in the state capitol of Ohio. And a police station was set ablaze in Minneapolis, where National Guard troops will again patrol the streets on Friday. The president tweeted early Friday that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts,” which frames the problem backward. It is not a defense of torching a Target to note that police abuse of civilians often leads to protests that can spiral out of control, particularly when met with force.

Police officers don’t face justice more often for a variety of reasons — from powerful police unions to the blue wall of silence to cowardly prosecutors to reluctant juries. But it is the Supreme Court that has enabled a culture of violence and abuse by eviscerating a vital civil rights law to provide police officers what, in practice, is nearly limitless immunity from prosecution for actions taken while on the job. The badge has become a get-out-of-jail-free card in far too many instances.

In 1967, the same year the police chief of Miami coined the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts” to threaten civil rights demonstrators, the Supreme Court first articulated a notion of “qualified immunity.” In the case of police violence against a group of civil rights demonstrators in Mississippi, the court decided that police officers should not face legal liability for enforcing the law “in good faith and with probable cause.”

That’s a high standard to meet. But what makes these cases nearly impossible for plaintiffs to win is the court’s requirement that any violation of rights be “clearly established” — that is, another court must have previously encountered a case with the same context and facts, and found there that the officer was not immune. This is a judge-made rule; the civil rights law itself says nothing about a “clearly established” requirement. Yet in practice it has meant that police officers prevail virtually every time, because it’s very hard to find cases that are the same in all respects. It also creates a Catch-22 for plaintiffs, who are required to hunt down precedents in courts that have stopped generating those precedents, because the plaintiffs always lose. As one conservative judge put it in a U.S. district court in Texas, “Heads defendants win, tails plaintiffs lose.”

In the five decades since the doctrine’s invention, qualified immunity has expanded in practice to excuse all manner of police misconduct, from assault to homicide. As the legal bar for victims to challenge police misconduct has been raised higher and higher by the Supreme Court, the lower courts have followed. A major investigation by Reuters earlier this year found that “since 2005, the courts have shown an increasing tendency to grant immunity in excessive force cases — rulings that the district courts below them must follow. The trend has accelerated in recent years.” What was intended to prevent frivolous lawsuits against agents of the government, the investigation concluded, “has become a highly effective shield in thousands of lawsuits seeking to hold cops accountable when they are accused of using excessive force.”

The vast majority of police officers are decent, honest men and women who do some of society’s most dangerous work. They should be forgiven good-faith mistakes or errors in judgment. But in case after case, well documented now by body cameras and bystanders, too many bad cops go unpunished for policing their fellow citizens in ways that often leave them abused or dead. No official tally of deaths at the hands of police officers is maintained in the United States, a reality that defies common sense in our hypercataloged society, but estimates from journalists and advocacy groups put the number of Americans killed by the police north of 1,000 per year. Black Americans are killed by the police at a much higher rate than white Americans.

When citizens dare to protest police violence, say by kneeling at a sporting event, they are branded “anti-police” and un-American. With a shrinking recourse in the courts and a fierce headwind of social resistance to reforming the way the nation is policed, is it any wonder that many enraged Americans take to the streets — in the midst of a global pandemic, no less — to demand that their country change?

As the militarization of police tactics and technology has accelerated in the past two decades, pleas from liberals and conservatives to narrow the doctrine of qualified immunity, and to make it easier to hold police and other officials accountable for obvious civil rights violations, have grown to a crescendo. The Supreme Court is considering more than a dozen cases to hear next term that could do just that. One case involves a police officer in Georgia who, while pursuing a suspect, held a group of young children at gunpoint, fired two bullets at the family dog, missed and hit a 10-year-old boy in the arm. Another involves officers who used tear gas grenades to enter a home when they’d been given a key to the front door.

There are few things that Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Justice Clarence Thomas agree on, at least when it comes to the letter of the law. Both have expressed deep concern over the court’s drift toward greater and greater qualified immunity for police officers. (“By sanctioning a ‘shoot first, think later’ approach to policing, the Court renders the protections of the Fourth Amendment hollow,” Justice Sotomayor once wrote.) With the next George Floyd just a bad cop away, one hopes the other justices will be moved to ratchet back qualified immunity to circumstances in which it is truly warranted. When bad cops escape justice and trust between the police and the community shatters, it isn’t just civilians who suffer the consequences, it’s the good cops, too".

Opinion | George Floyd, Police Accountability and the Supreme Court - The New York Times

Opinion | Of Course There Are Protests. The State Is Failing Black People. - The New York Times

"The collapse of politics and governance leaves no other option.

Ready or not, life is returning to some sort of normal in the United States, and normal inevitably includes police officers killing an unarmed black man in their custody, followed by street protests. The country is working its way back into its familiar groove.

This time it’s Minneapolis. Thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest the killing of George Floyd by a police officer who pressed his knee into Mr. Floyd’s neck for a breathtaking seven minutes as he lay pinned on the ground in handcuffs. Mr. Floyd’s pleas for help — repeating that he couldn’t breathe, calling out for his dead mother — were ignored. The three other police officers who watched seemed uninterested in the life they were violently snuffing out in front of a crowd gathered in disgust.

Elected officials from Minnesota denounced the brutality. Jacob Frey, the mayor of Minneapolis, said, “Being black in America should not be a death sentence.” Others, including Senator Amy Klobuchar, who hopes to emerge as Joe Biden’s running mate, expressed a range of public emotions that have become commonplace: shock, horror, promises of investigation and pleas for calm. In a rare rebuke, the four officers involved have been fired.

But the fact that Mr. Floyd was even arrested, let alone killed, for the inconsequential “crime” of forgery amid a pandemic that has taken the life of one out of every 2,000 African-Americans is a chilling affirmation that black lives still do not matter in the United States.

It is easy to understand the response of multiracial protesters in Minneapolis. (If you look closely, hundreds of white people are participating; the intersecting injustices are also apparent to them.) This spring season has bloomed at least 23,000 Covid-19-related deaths in black America. The coronavirus has scythed its way through back communities, highlighting and accelerating the ingrained social inequities that have made African-Americans most vulnerable to the disease.

This unbelievable loss of life has taken place while restrictions were at their tightest and social distancing at its most extreme. What will happen when the country fully reopens, even as the number coronavirus cases continues to grow? As mostly white public officials try to get things back to normal as fast as possible, the discussions about the pandemic’s devastating consequences to black people melt into the background, consequences which become accepted as a “new normal” we will have to live or die with. If there were ever questions about whether poor and working-class African-Americans were disposable, there can be none now. State violence is not solely the preserve of the police.

It’s not just the higher rates of death that fuel this anger, but also publicized cases where African-Americans have been denied health care because nurses or doctors didn’t believe their complaints about their symptoms. Just as maddening is the assumption that African-Americans have particularly bad health and thus bear personal responsibility for dying in disproportionate numbers.

Instead of using this monumental crisis to change the conditions feeding the rapid rate of black deaths, the armed agents of the state continue their petty, insouciant policing. Even seemingly innocuous instructions for social distancing become new excuses for the police to harass African-Americans. In New York, blacks made up a staggering 93 percent of coronavirus-related arrests. There are similar racial disparities in Chicago. At a time when police departments have pledged to arrest fewer people to stem the spread of the virus in local jails and in the name of preserving public health, African-Americans remain in their cross hairs. After all, why were the police arresting George Floyd for forgery, a “crime” of poverty committed by desperate low-wage workers, in the first place?

When white protesters, armed to the teeth in Michigan and elsewhere, make threats against elected officials, the president praises them as “very good people” and they are largely left alone. They are certainly not suffocated to death on the street. In contrast, after Minnesota’s governor activated the National Guard on Thursday evening, the president suggests that those who protest police brutality could be shot. Protesters in Minneapolis are met with tear gas and projectiles launched by police officers, even as many other public officials claim to sympathize with their anger. These double standards are part of what roils Minneapolis and also why the potential for this kind of eruption exists in every city.

The anger exploding on the streets runs much deeper than the obvious hypocrisies in the disparate treatment of white, conservative protesters and a multiracial crowd of people objecting to police brutality. Over the last several weeks, there has been the taped murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, the vicious shooting of Breonna Taylor by the Louisville police and the killing of Tony McDade, a black trans man, by police officers in Tallahassee. These cases were ignored until public outcry forced the nation to pay attention, even as the public has been riveted to the news because of stay-at-home orders. Meanwhile, there is the highly publicized case of a white woman in Central Park calling the police on a black man when he asked her to put her dog on a leash. The potential consequences of that call were made clear by the killing of George Floyd.

But what is also unmistakable in the bitter protests in Minneapolis and around the country is the sense that the state is either complicit or incapable of effecting substantive change.

As the Democrats’ presumptive presidential nominee jokes that African-Americans who don’t vote for him are not black, the crisis in black communities seems most acute and overlaps with almost daily incidents of police violence or some other oppressive expression of state power. It was a joke that Joe Biden thought would show his “insider” status with black voters. Instead, it made him look arrogant in assuming he has standing among young or working-class African-Americans. He sounded like any other well-heeled politician who has failed to grasp the enormity of the challenges.

This simultaneous collapse of politics and governance has forced people to take to the streets — to the detriment of their health and the health of others — to demand the most basic necessities of life, including the right to be free of police harassment or murder.

What are the alternatives to protest when the state cannot perform its basic tasks and when lawless police officers rarely get even a slap on the wrist for crimes that would result in years of prison for regular citizens? If you cannot attain justice by engaging the system, then you must seek other means of changing it. That’s not a wish; it’s a premonition.

The convergence of these tragic events — a pandemic disproportionately killing black people, the failure of the state to protect black people and the preying on black people by the police — has confirmed what most of them already know: If we and those who stand with us do not mobilize in our own defense, then no official entity ever will. Young black people must endure the contusions caused by rubber bullets or the acrid burn of tear gas because government has abandoned us. Black Lives Matter only because we will make it so.

This is not new in our history. After World War II, city-dwelling African-Americans saw the contradictions in a society that put a man on the moon, while allowing rats to maul black children in their cribs at night. The federal government underwrote the substandard housing that African-Americans were consigned to because of residential segregation. Everywhere African-Americans looked, the state was not only impervious to their suffering but an accessory to the crime.

This was the source of the black urban uprisings that swept cities around the country in the 1960s, the same era as the civil rights movement in the South. The failure of the state to deliver anything African-Americans were demanding left hundreds of thousands to take things into their own hands. It didn’t matter then, as it doesn’t matter now, whether white society approves or disapproves; what mattered was that formal mechanisms for social change failed to function, compelling African-Americans to act on their own behalf.

Six years ago, the protests in Ferguson, Mo., set the stage for the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, which is rooted in similar kinds of social incongruities. It was paradoxical that this new movement emerged in the shadow of the country’s first African-American president and the presence of more African-Americans in Congress than at any other point in history. And yet the amassing of that black political power could not stop the quotidian police brutality. Just as it couldn’t stop the collapse of black homeownership, the expansion of the racial wealth gap or the avalanche of student loan debt yoked to the credit reports of black millennials.

It did not matter if the expectations were too grandiose for what a black president could accomplish. What mattered was that when government failed to make a substantive difference in people’s lives, African-Americans protested to make black lives matter."

Opinion | Of Course There Are Protests. The State Is Failing Black People. - The New York Times

7 People Shot at Louisville Protest Over the Death of Breonna Taylor - The New York Times

/https%3A%2F%2Fstatic01.nyt.com%2Fimages%2F2020%2F06%2F28%2Fmultimedia%2F28louisville-protest%2F28louisville-protest-articleLarge.jpg%3Fquality%3D75%26auto%3Dwebp%26disable%3Dupscale)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstatic01.nyt.com%2Fimages%2F2020%2F05%2F29%2Fworld%2F29louisville-1%2F29louisville-1-articleLarge.jpg%3Fquality%3D90%26auto%3Dwebp)

Thursday, May 28, 2020

2 Days in May That Shattered Korean Democracy

2 Days in May That Shattered Korean Democracy

The US response to a dictatorship’s repression in Gwangju in 1980 was even worse than we thought.

By Tim Shorrock and Injeong Kim

Today 1:25 pm

On May 18, South Koreans paused to mark the 40th anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, one of the most traumatic days in their history. The 10-day revoltwas triggered when students and citizens protesting a military coup by a renegade general were attacked by airborne special forces with a viciousness and cruelty that Koreans had not experienced since the darkest days of the Korean War.

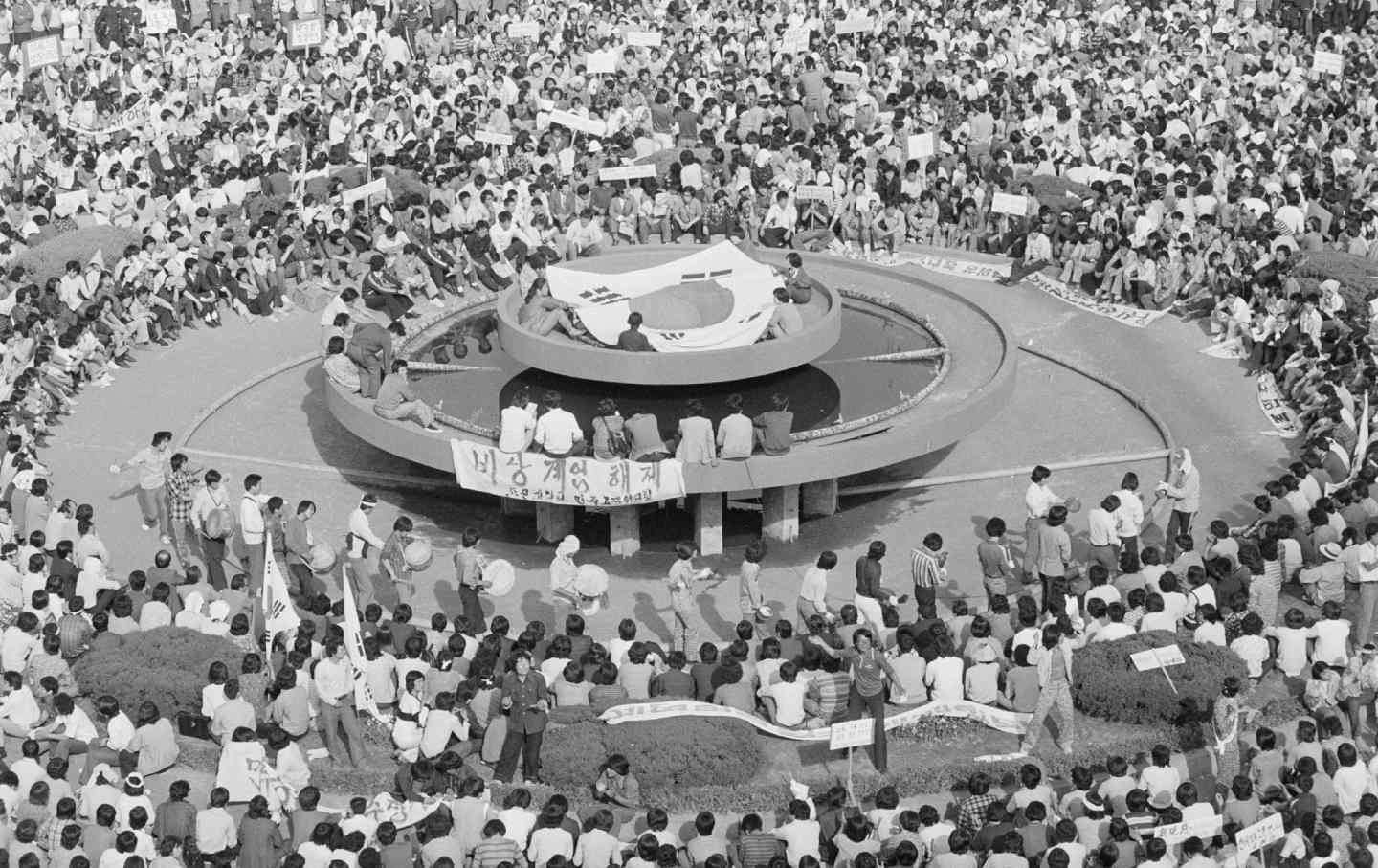

The armed resistance by Gwangju’s Citizen Militia liberated the city from the marauding troops. The townspeople, freed from decades of military rule, kept their city running, buried their dead, and transformed themselves into a self-organized system of mutual aid they now call the Gwangju Commune.

Those who died in Gwangju “believed that the survivors would manage to open up a better world” and “were convinced that the defeat of that day would become the victory of tomorrow,” President Moon Jae-in declaredon May 18 in the city square where protesters were killed in 1980.

But their dream of a just society was snuffed out on May 27 by Korean Army troops, who were released from their usual duties on the border with North Korea to reoccupy Gwangju. The official death toll from the uprising stands at 165, but residents believe that more than 300 people were killed, with dozens still unaccounted for.

Despite that defeat, Gwangju’s resistance is now seen as the first shot in the mass movement that, in 1987, swept aside a quarter-century of dictatorship to create one of the world’s most impressive democracies. After years of hostility by conservative governments and attacks on its legitimacy by South Korean rightists, the Gwangju Uprising is widely celebrated in art, music, literature, and film.

President Moon, who came of age as a political activist during South Korea’s authoritarian era, promised to give momentum to an independent truth commissionthat is investigating the Korean military’s use of force, including the question of who ordered the firing on civilians and sent a helicopter to strafe a building near Gwangju’s center. The commission, he said in an interview with the Gwangju affiliate of broadcast company MBC, would also seek to identify individuals who sought to “conceal and distort the truth” of the Gwangju Uprising.

That’s a tall order, because that trail leads straight to the United States and its president, Jimmy Carter, who ran for office in 1976 vowing to make human rights the centerpiece of American foreign policy. Sadly, he failed to do that in Gwangju, sparking the worst crisis in US-Korean relations since 1945. What happened there stoked years of anti-American sentiment, and Gwangju has remained a point of contention ever since.

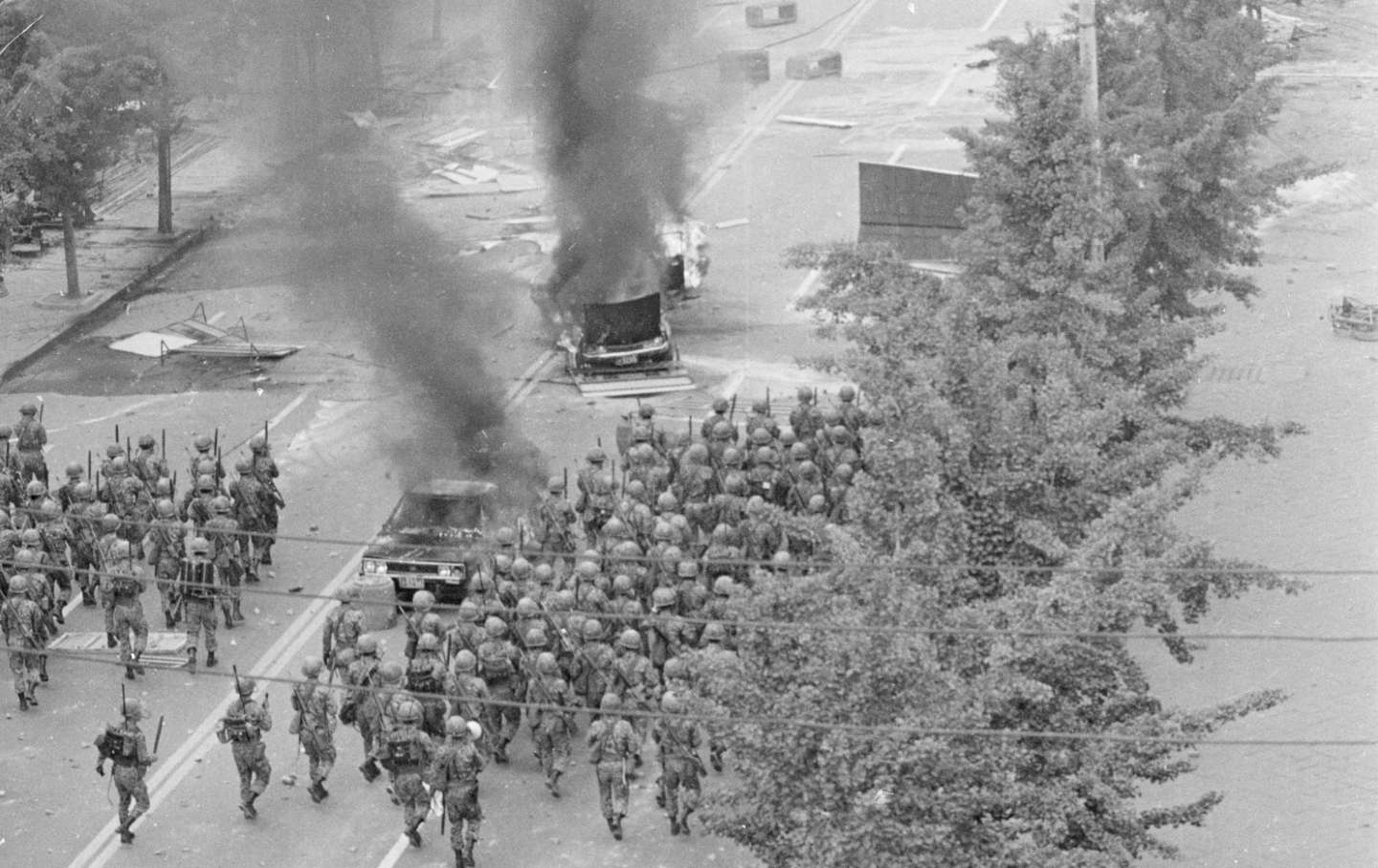

Geumnam-ro, where the airborne troops opened fire on protesters on May 21, 1980. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

As some Koreans are painfully aware, the Carter administration played an essential role in Gwangju by helping the coup leader, Lt. Gen. Chun Doo-hwan, crush the uprising. At a high-level White House meeting on May 22 that we first reported in 1996, Carter’s national security team approved the use of force to retake the city and agreed to provide short-term support to Chun if he agreed to long-term political change (that, of course, didn’t happen until he was forced out by massive protests in 1987).

The stakes were high, and were exacerbated for US policy-makers by the simultaneous crisis over the Islamic revolution in Iran, which eventually brought Carter’s presidency down. As the once-secret minutes to the White House meeting show, plans were also discussed for direct US military intervention in Korea if the situation in Gwangju spiraled out of control.

Within days of the May 22 meeting, the US commander in Korea, Gen. John Wickham, released two divisions of Korean Army troops from the US-South Korean Combined Forces Command (CFC) to retake the city. Fearing that North Korea could intervene, the Pentagon also asked the Korean military to delay its assault on Gwangju to give the US military time to dispatch an aircraft carrier and several spy planes to the peninsula, according to 1989 testimony by South Korea’s martial law commander at the time.

Under that cover, Chun’s forces reentered the city and killed the remaining rebels. Hundreds more were hunted down and tortured in a military prison in Gwangju (it’s now a museum where former prisoners work as guides).

Chun was tried and convicted in 1996 of treason and murder, but he was later pardoned. To this day, he continues to deny any responsibility for the mass killing. In its official statements about the incident, the United States has consistently described Gwangju as a domestic issue for South Korea. “When all the dust settles, Koreans killed Koreans, and the Americans didn’t know what was going on and certainly didn’t approve it,” a State Department official said in 1996 when the White House meeting was first reported.

Carter, who has won global praise for his humanitarian actions since leaving the presidency, has never spoken publicly about his actions in Gwangju (through an intermediary, he declined to comment for this article). His most extensive remarks came in an interview on CNN on June 1, 1980, when he was asked by the journalist Daniel Schorr if US policy in Korea reflected a conflict between human rights and national security.

“There is no incompatibility,” Carter snapped. South Korea, he said, typified a situation where “the maintenance of a nation’s security from Communist subversion or aggression is a prerequisite to the honoring of human rights and the establishment of democratic processes.” Shamefully, none of this was true.

As two of the principal journalists who have investigated US involvement in Gwangju, we know there is much more to the story. Over the past five years, we have interviewed dozens of participants and survivors of the uprising as well as many of the US officials involved in the decision-making that May.

Now, at a time of growing tensions between Seoul and Washington over North Korea and the cost of US military bases in the South, we have uncovered deeper evidence of US complicity in Gwangju and what the US government knew and when it knew it. The story is much worse than we thought.

- When Carter’s White House made the decision to support Chun’s crackdown on the rebellion, it knew that 60 people in Gwangju had been shot to death and over 400 injured just 24 hours earlier, and that Chun was directly responsible. We learned that from notes taken by a senior Pentagon official who was present at the critical White House meeting on May 22.

- General Wickham, the US commander, was fully briefed on the Korean Army’s planning for the May 27 assault on Gwangju in a May 21 meeting with Gen. Lew Byung-hyun, the CFC’s deputy commander. Lew, in turn, told the US general that he was carrying out the wishes of Chun and the coup leaders. Wickham himself confirmed this.

- The US contingency plans for Gwangju included sending additional US ground forces into Korea, a volatile proposal that has never been disclosed before and indicates how seriously US commanders and the Carter administration viewed the situation. If it had escalated, “we would have been much more aggressive” and asked for “additional support from the Pacific Command to suppress the unrest,” General Wickham told us.

- The prime mover in the May 22 meeting was Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, who had been deeply involved over the previous three years restoring once-frayed ties between the US and South Korean militaries and strengthening the Cold War alliance between the US, Korean, and Japanese armed forces.

The Gwangju Uprising was the culmination of a series of events that unfolded in South Korea after the assassination of the former dictator, Park Chung-hee, on October 26, 1979. Fed up with 18 years of harsh dictatorship, Korean students and workers began agitating for a return to democracy. As tensions escalated over the next six months, General Chun and a small group within the military launched a rolling coup, taking over the military, the Korean CIA, and then, on May 17, the government itself.

Protesters and paratroopers clashed for 3 days in Gwangju’s streets. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

“This might have been the longest coup d’état in world history,” says Prof. Kwang Ho Chun, a military strategy specialist and professor of international studies at Jeonbuk National University in North Cholla Province.

In the months before the coup, US officials, led by diplomat (and liberal icon) Richard Holbrooke, tried to find a middle ground between the martial law forces and the pro-democracy movement [see Shorrock, “Debacle in Kwangju,” The Nation, December 9, 1996]. “The United States had at least five months to support Korean democracy,” but failed, Professor Chun said in his interview. While the US emphasis during Gwangju on Korean security was understandable, he said, US officials should have recognized that “sometimes democracy can improve a security situation much faster” than military action.

In fact, as the rebellion intensified, Carter and his advisers began to see it as a much greater threat than Chun’s violent takeover of the government. The situation came to a head over a 48-hour period between May 21, 1980, when Chun’s forces opened fire on the people of Gwangju, and May 22, when the United States threw its support behind the Korean generals.

“May 21, 1 pm, was a very critical point,” Lee Jae-eui, an activist and writer who witnessed the massacre in front of Gwangju’s provincial capitol building, told us as he stood on the exact spot of the firing years later.

For three days, Chun’s paratroopers had used boots, clubs, bayonets, and even flamethrowers to terrorize the city, filling the morgues with the dead and overwhelming the hospitals with bodies ripped apart by the violence. Angered and shocked beyond measure, the people, led at first by young students and joined by taxi drivers, bus drivers, shopkeepers, gangsters, and prostitutes, fought back with vehicles and their own handmade weapons.

By midday, hundreds of thousands of furious Gwangju residents surrounded the paratroopers, who had made their stand at the old capitol building. Suddenly, and without warning, Lee says, the troops opened fire.

Repeated volleys from M-16s turned Gwangju’s now-famous Geumnam-ro Street into a scene of carnage. “I saw so many people killed, so many injured, with blood everywhere,” recalls Lee. “I suddenly had a very strange feeling, that I had to join the struggle to fight the military.” The massacre was indelibly sealed in Korean memory in A Taxi Driver, the acclaimed 2018 film starring Song Kang-ho, the beloved character actor from the Academy Award–winning Parasite.

In the hours that followed, Gwangju residents raided police stations and armories in nearby towns and grabbed carbines and other weapons, and by that evening had taken over the city. But tragically, as recounted in Lee’s famous book about the uprising, Kwangju Diary: Beyond Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age, many of the fighters naively believed that the United States, as the champion of democracy, would come to their aid.

Then came the invasion on May 27. “The citizens of Gwangju felt completely betrayed by the US government and believed that US statements about human rights only extended to the right kind of people and not to them,” says David Dollinger, a former Peace Corps volunteer who was one of the few Americans who remained in the city during the uprising and spent time with the armed rebels in the hours before they were killed.

According to Dollinger, who now lives in London, Gwangju’s hopes for US assistance were raised when people in the city heard reports that a US aircraft carrier had been deployed to Korean waters. But their optimism faded when they learned that troops had been moved from the DMZ and were headed for the city. “By that time, they knew there would be no peaceful ending,” he said. They were right: The Carter administration had already decided their fate in the meeting on May 22.

“At that time, the belief [in Washington] was that 60 were dead and 400 wounded,” said Nicholas Platt, who was a deputy assistant secretary of defense and a senior aide to Defense Secretary Brown. Platt is one of the few people still alive who attended the May 22 White House meeting. During an interview in 2017 at his office at the Asia Society in New York, he pulled out a sheaf of notes he had taken during the meeting and allowed us to film him reading them; their contents are explosive.

At the meeting, Platt recalled, “Gwangju was the main issue.” Yet, judging from his notes and the official minutes, there was no discussion whatsoever about what the people of Gwangju had suffered. Instead, the entire discussion revolved around security. “There was unrest in Gwangju and the Korean military was moving troops in,” said Platt. “We were worried whether they would be able to restore order. There were units that had been moved from the DMZ and we thought that might lessen our ability to deal with the North Koreans.”

Lee, when shown Platt’s notes, was shocked to hear that US officials had such detailed numbers on casualties only 36 hours after the firing on Geumnam-ro. “That number was concealed by the coup leaders,” he said last week, and was not even known to the Korean public until South Korea’s newly elected National Assembly held hearings in 1988.

Hundreds of people in Gwangju were killed by Chun Doo-hwan’s paratroopers. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

We also interviewed General Wickham about his meetings with General Lew, his deputy commander at the CFC (then, as now, the US commander of the CFC controls all US and Korean troops during times of war). Significantly, they met on the afternoon of May 21, within hours of the mass shooting in Gwangju.

“Lew and I met several times a day on Gwangju,” Wickham said in an interview at his home in Texas in 2017. The gist of his conversations, he said, were then relayed via “secure phone” to the other members of the US country team in Seoul, Ambassador William Gleysteen and CIA station chief Robert Brewster.

“General Lew was worried about Gwangju morphing into warfare around the country, and he wanted to tamp it down the best he could. That’s why he and I talked about how to do that with minimal force [and] what’s the best way to do it” said Wickham. But, in carrying out the operation, Lew and other Korean commanders understood they were doing the bidding of General Chun and the officers who had seized control of the army in December.

“The coup leaders were saying we have to suppress this, it’s a threat to our coup,” Wickham recalled of his conversation with General Lew (in 1981, after Chun became president, Lew was named South Korea’s ambassador to the United States, maintaining his role as a key liaison with Washington). Brewster and Gleysteen sent the information from Wickham’s meeting to Washington in top secret cables (which we later obtained) in preparation for the White House meeting the next day.

In a critical but highly redacted report, the CIA declared that “the insurrection in Kwangju…poses a serious challenge to the Martial Law Command’s authority.… Violence has spread to about 16 towns within a 50-mile radius of Kwangju, all in South Cholla Province.”

While “trying to negotiate a cease-fire,” the military “probably will have to use force to end the rebellion,” the agency concluded, adding that Korean generals “would be hard pressed to deal with simultaneous uprisings of the same magnitude in other areas.” These words were repeated almost verbatim by Gleysteen in his cables, who added this observation about Chun and his martial law group: “The December 12 generals obviously feel threatened by the whole affair.”

Given the overwhelming focus on a military response, it’s no surprise that, as Platt’s notes reveal, Defense Secretary Brown was the dominant figure in these deliberations. This was a natural progression from his role as the chief US interlocutor with the Korean military before and after Park’s 1979 assassination.

Brown and the Joint Chiefs were in constant contact with the Korean military leadership, even after General Chun seized control of the army in his December 12 coup. As shown in Platt’s notes, Brown’s forceful views overrode others who were deeply concerned about Chun, such as Warren Christopher, then the deputy secretary of state.

“Chun has done real harm and set the process back,” Christopher said at one point in the meeting. His boss, Secretary of State Edmund Muskie, agreed, saying that Chun “could become a liability,” and asking, “Aren’t we going to be hostage to them?” When David Aaron, an aide to National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, raised the possibility of urging Chun to step down, Brown intervened. “If he goes that will create a vacuum.” Brown said, according to Platt’s notes.

Worse, the defense secretary even seemed to admire Chun and his martial law group. “They have been quite good about using force,” he said. With Chun clearly in control, said Platt, Brown’s Pentagon even established “a special channel” between the general and the Joint Chiefs of Staff through Gen. John Vessey, the deputy chief of staff of the US Army who had been the US commander in Korea prior to Wickham and knew Chun well.

For Koreans, one of the most enraging aspects of this meeting was Brown’s statement, as recorded by Platt, that Koreans would accept the administration’s support for Chun because “Koreans go with who’s winning.” Months later, General Wickham would amplify this thought in public, saying that Koreans were “lemmings” who would follow any strong leader.

Such comments reflect the predominant thinking among US leaders at the time that Koreans were simply not ready for democracy and would easily accept another military strongman, even after 18 years of dictatorship. Brown, who died in 2019, did not respond when we contacted him in 2017.

Brown’s official biography portrays him as a valiant fighter for Korean democracy, emphasizing his forceful meeting with President Chun in December 1980 to persuade him not to execute Kim Dae-jung, the dissident leader who would later be elected president. As for the White House meeting about Gwangju on May 22, 1980, the bio blandly notes that participants “decided that the ROK had to resume authority in Kwangju” before the United States could resume its pressure for liberalization. That’s an interesting euphemism for helping to put down an insurrection against brutality.

This traffic circle was the center of the uprising. Today it is known as Democracy Plaza. (May 18 Memorial Foundation)

This May 11, as this article was being prepared, the State Department, acting “in the spirit of friendship and cooperation between allies,” released several dozen newly declassified documents related to Gwangju to the Moon government in Seoul. Many were first released in redacted form 24 years ago, and most are fairly innocuous, apparently designed to put US policy in the best light possible. But one of the cables illustrates the kind of disinformation that the Carter administration relied on to make its decisions about Gwangju.

On May 18, 1980, Gen. Lee Hui-sung, the martial law commander, toldAmbassador Gleysteen that if the uprising in Gwangju was not contained, South Korea ”would be communized in a manner similar to Vietnam.” Given what had inspired the uprising, this statement was ludicrous, but it was apparently enough to convince Carter and his advisers that they were on the right course. A spokesperson for Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, asked to comment on Carter’s policy at the time, said she had “nothing to add” to previous US policy statements.

Ironically, the CIA may have had the best understanding in the US government about Chun. In 1987, as anger was building in Seoul over Chun’s repressive rule, the agency informed the Reagan administration that Chun’s crackdown in Gwangju had led many Koreans to believe that his military was a greater threat to their security than North Korea.

“A tarnishing of the military’s image—the result of its close association with the highly unpopular rule of [Chun] and the Army’s brutal suppression of riots in Kwangju in 1980—has convinced many officers that South Koreans have grown antagonistic toward them and complacent about the North Korea threat,” the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence wrote in a secret assessment of the Korean military.

But only after the protests in the summer of 1987 threatened to create another Gwangju did Chun agree to step down and allow direct presidential elections for the first time. Out of that struggle, and inspired by the Gwangju democratic movement of 1980, South Korea’s democracy was born.

The Korean people did it again with the Candlelight Revolution of 2016–17, which led to the impeachment of another unpopular president, Park Geun-hye (the daughter of former dictator Park Chung-hee) and the subsequent election, in May 2017, of Moon Jae-in. The real “winners” of Korean history, in other words, were the citizens of Gwangju. But, sadly, they and many other Koreans had to suffer under military dictatorship for seven more years after their uprising.

Should the United States apologize for what happened in Gwangju in 1980? The Nation put that question to President Moon in an interview in Gwangju three days before his election. Moon, characteristically, rejected the notion. “It doesn’t matter, because we have moved on, and established democracy for ourselves,” he said. An official in Moon’s Blue House, citing the “government to government” discussions going on about the investigation into May 18, would not comment.

But given what we know now about US actions during Gwangju, the time has come for a formal apology, those who survived the uprising say. “They have to give a sincere apology,” says author Lee, who is famous in Gwangju for his continued activism on the issue. David Dollinger, the former Peace Corps volunteer, is adamant on the question.

“When I think about Gwangju, I am brought to tears and am truly embarrassed by my government from that time,” he says. That feeling, in part, reflects his anger over being forced to resign from the Peace Corps after he went public with his critique at the time of the uprising. An apology, he says, “should be done not through documents but by an official of the US government kneeling to the mothers and citizens of Gwangju asking for forgiveness. It should then apologize to all the people of Korea, for not listening to its citizens.”